Editor’s Note: This analysis is part of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, which is a partnership between Economic Studies at Brookings and the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings.

High health care costs are a major concern for many families. One particular issue that has garnered attention in recent months is surprise out-of-network billing, where consumers receive very large bills for out-of-network care even though they did not intend to select an out-of-network health care provider.

Polls suggest that three quarters of Americans favor policies that would protect consumers from surprise bills, and lawmakers in Washington and in state capitols are considering action. Below, you can find answers to frequently asked questions about surprise billing.

What is “Surprise Billing”?

When people need medical care, they generally seek out providers that are in-network for their insurance. But there are situations where patients are unable choose which provider treats them, and thus may end up unexpectedly receiving care from an out-of-network provider. While patients typically select an in-network hospital and lead doctor for planned hospital care (like a scheduled surgery or the birth of a baby) and sometimes even choose a hospital in emergency situations, they do not choose every member of their care team. Instead, hospitals direct ancillary providers like anesthesiologists, radiologists, and emergency room doctors, to play a role in the care that the patient receives. These providers may be out-of-network even though the hospital is in-network. And in other emergency situations, patients may be taken to the nearest hospital, whether or not that hospital is in-network, and ambulance transportation may also be out-of-network.

When patients receive care from out-of-network providers that they did not choose, they may receive a “surprise” out-of-network bill. The insurance company will often pay some amount to the out-of-network provider, but typically less than the provider’s list price (or “charge”) for the services. In many such cases, the provider then “balance bills” the patient for the difference between their list price and the insurer’s payment.

How Big are Surprise Balance Bills?

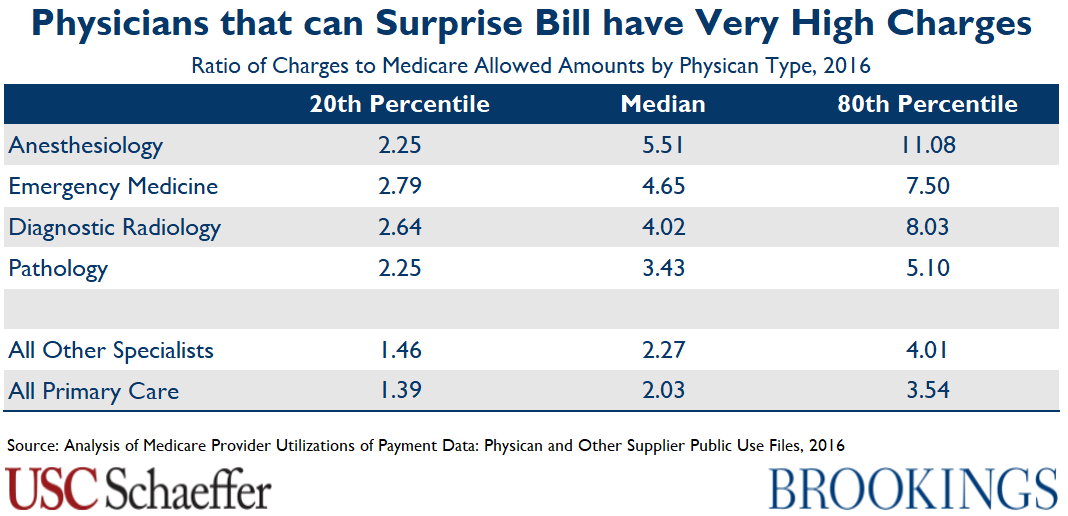

Surprise bills can be very large. Provider’s list prices are not negotiated between insurance companies and providers, and because consumers are not choosing the provider in these circumstances, they have no ability to shop around to avoid providers with high list prices. That means these list prices are not constrained by market forces and can be very high; indeed, the data show that the physician specialties that have the most opportunity to send surprise balance bills also have much higher list prices (as a percentage of what Medicare pays for those services) than other types of physicians.

How Common are Situations That Can Lead to Surprise Billing?

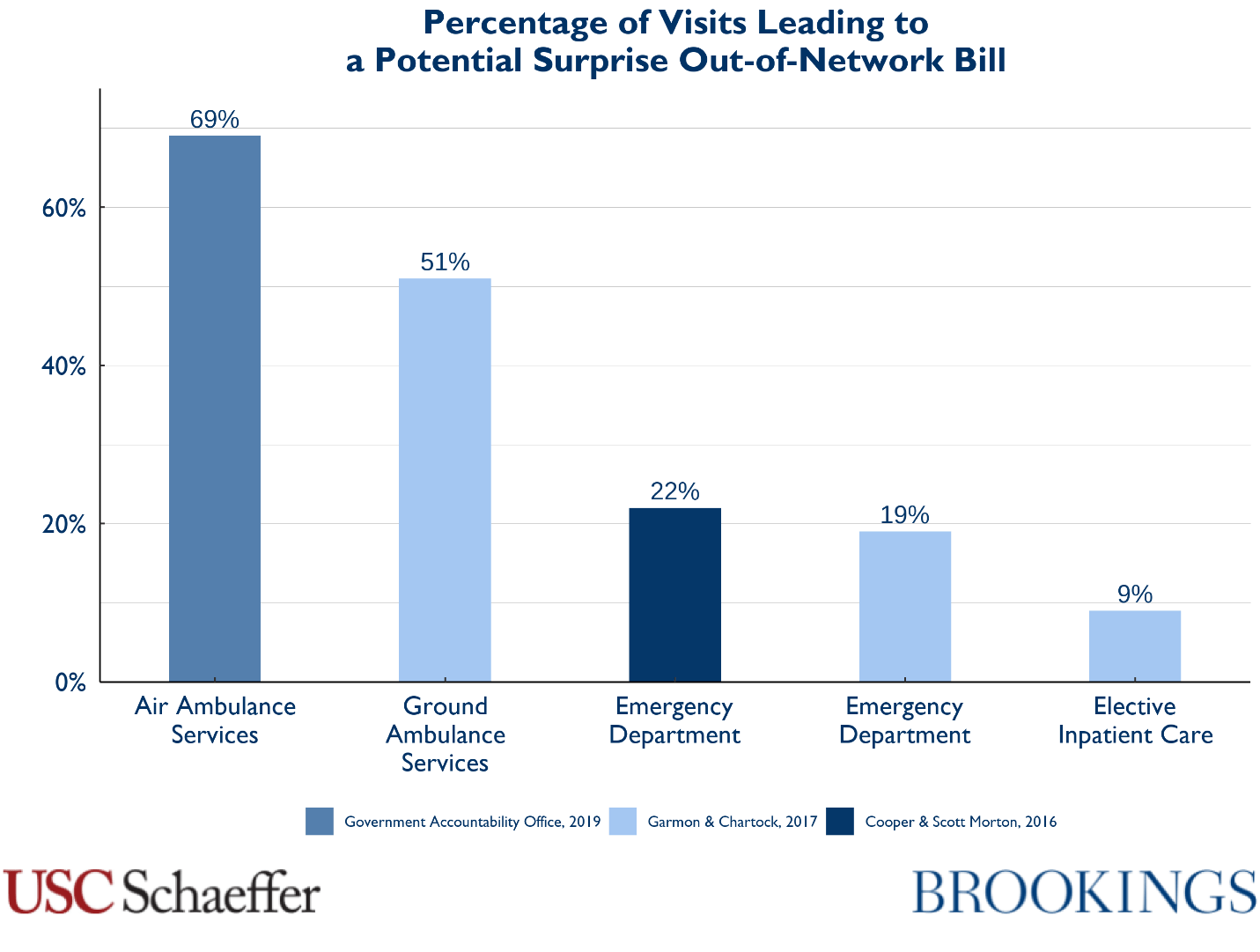

Out-of-network care delivered in situations that patients cannot reasonably avoid is fairly common. Researchers find that about 20% of emergency department visits involve care from at least one out-of-network provider. Similarly, about 9% of elective inpatient admissions involve at least one out-of-network provider. And studies suggest that between half and two-thirds of ambulance rides are out-of-network.

Why Does it Happen So Often?

Surprise billing reflects efforts by providers to exploit a market failure: the fact that patients do not choose their emergency and ancillary providers, who are allowed to contract independently with insurance plans. That gives these physicians a lucrative out-of-network billing opportunity: they can remain out-of-network, collect some amount directly from insurance companies, and balance bill patients after the fact up to a list price that is much higher than what they might receive if they agreed to join an insurer’s network.

Importantly, this option is only available for providers that patients do not choose. In other specialties (like surgeons, obstetricians, or primary care providers), providers generally face strong pressure to enter at least some insurance company networks, since few patients would choose an out-of-network doctor. But providers that patients do not choose can leverage the fact that they can remain out-of-network to receive very large payments relative to their peer physicians.

How Does This Affect Healthcare Consumers?

Patients who receive a surprise balance bill can be expected to pay hundreds, thousands, or even tens of thousands of dollars. But surprise billing also leads to higher premiums for all health care consumers.

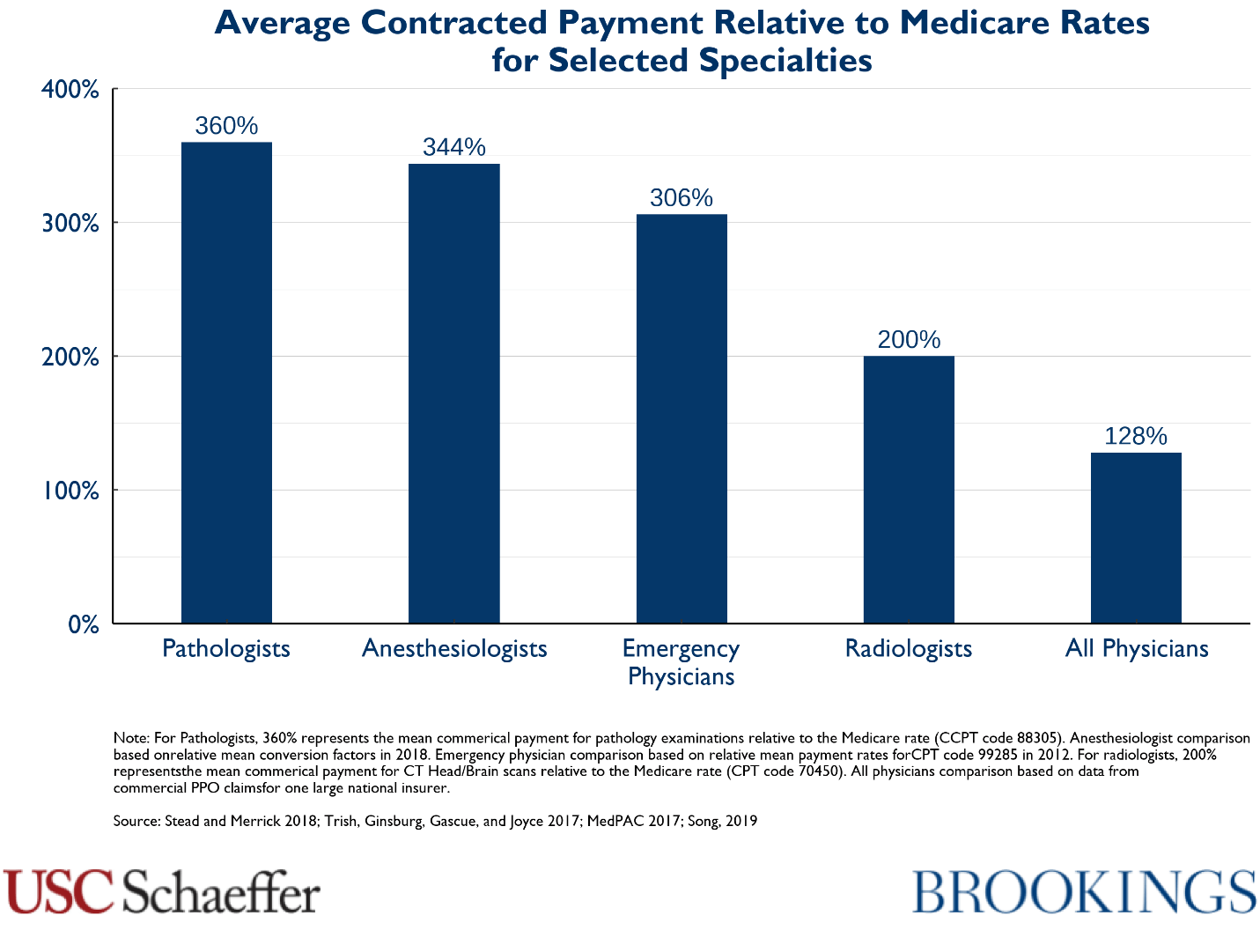

Because these providers can credibly threaten to remain out-of-network and balance bill patients, they are able to demand very high rates from insurance companies when they do go in-network. As the figure below shows, specialists like anesthesiologists and emergency medicine physicians receive payment rates roughly double what their peer physicians get (as a percent of what Medicare would pay for the same service) when they do go in-network.

That means all consumers with private insurance pay higher premiums because this relatively small group of providers is able to exploit a market failure. Extrapolating from Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates, if these providers were paid more in line with other specialists relative to Medicare rates, commercial insurance premiums would be roughly 5% lower than they are today.

What Can a Consumer Who Receives a Surprise Balance Bill Do?

In some states, commercially-insured consumers may be protected by a state law that aims to prevent or limit surprise billing. Consumers in 27 states may be able to obtain assistance from their state Department of Insurance, though state law protections may not cover all surprise billing situations, and may not cover people with insurance through their job.

Consumers who are not protected by a state law can contact their insurance company and the provider who sent the bill. The provider may agree to write-down a portion of the payment or to schedule a repayment plan over time. Consumers may be able to appeal to their insurance company to argue that the insurer should pay a greater portion of the bill. The state Department of Insurance or their employer’s HR department may also be able to provide some advice.

What Can Policymakers Do?

Policymakers can address the market failure and put an end to surprise billing, but they should take care to ensure that their solution to the surprise billing problem does not increase health care costs for everyone.

One type of solution (which we term “billing regulation”) would require insurance companies and providers to charge the patient only the amount she would have paid had she seen an in-network provider. This ensures that the patient will have the same costs regardless of whether the provider selected for her is in-network or out-of-network.

Policymakers using this framework may also wish to specify a mechanism to decide how much the insurance company must pay the provider for the care received. There are many options: providers could be paid a rate based on what Medicare would pay for the service, a rate based on what insurers pay other providers for the service, or there could be an arbitration process. We believe it is important that policymakers choose a rate that is relatively low: this group of providers are today receiving higher payments than peer physicians, and policymakers have an opportunity to address this imbalance (or at least refrain from making it worse). For more information on options for setting this rate, see our analysis of different billing regulation approaches.

Another type of solution (termed “contracting regulation”) would prevent these types of providers from being out-of-network in the first place. This includes “network matching” policies that require doctors to join the same networks as the hospitals in which they practice, or prohibiting emergency and ancillary clinicians from billing insurers or patients directly for their services, instead making them reliant on the facility they work at for payment – similar to how nurses are paid today.

You must be logged in to post a comment.