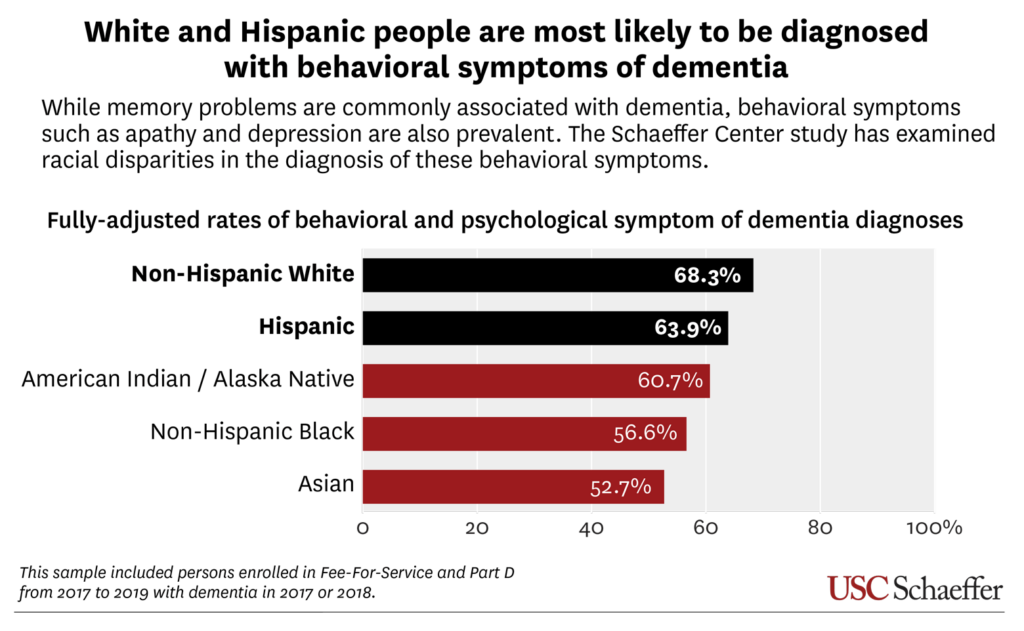

Compared to Black and Asian people, white and Hispanic people with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias were most likely to be diagnosed with symptoms like depression and agitation, according to a new study from the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics.

White and Hispanic people with these diagnoses were also most likely to be prescribed central nervous system (CNS) active drugs, including antidepressants, antipsychotics and anticonvulsants. Yet, these drugs have been associated with higher risk of falls, cardiovascular events, hospitalization and death, according to the study published today in the Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease.

Additionally, the study found:

- Among all people with a diagnosis of behavior and psychological symptoms of dementia (BPSD), 78.6% used a central nervous system (CNS) drug, driven largely by antidepressants (58.1%);

- Hispanics (67.6%) and whites (66%) were most likely to use a CNS drug; Blacks (58.6%) and Asians (54.5%) were least likely.

While memory problems are the most well-known symptoms associated with dementia, behavioral symptoms like apathy and depression are also common and can greatly impact quality of life for people with dementia, their families, and caregivers. USC Schaeffer Center researchers recently set out to understand how common these symptoms are, and whether there are differences in their diagnosis and treatment across racial and ethnic groups.

Their study examined Medicare claims data for people diagnosed with dementia from 2017 to 2019, before the COVID-19 pandemic swept the country and disrupted the healthcare system. Unlike previous studies, their research represented 100% of community-dwelling people living with dementia who were enrolled in Medicare Fee-for-Service, and estimates were based on clinical diagnoses from medical claims.

“The open question remains: Are there actually higher rates of, say, depression among white people with dementia? Or are there cultural or other barriers that are keeping Black and Asian people with dementia from getting a diagnosis and potential treatment?” said study lead author Johanna A. Thunell, a research scientist at the USC Schaeffer Center.

“Central nervous system drugs used to treat dementia symptoms may improve quality of life for persons living with dementia and their caregivers, but these drugs are also potentially harmful,” said the study’s senior author, Julie M. Zissimopoulos, co-director of the Aging and Cognition program at the USC Schaeffer Center and a professor at the USC Sol Price School of Public Policy. “Patients, families and their providers will need to consider the tradeoffs.”

“We also found substantial differences in who was taking individual drugs classes. For example, while white people were most likely to take antidepressants, American Indian and Alaska Natives had the highest rates of opioid prescriptions,” said study coauthor Geoffrey Joyce, director of Health Policy at the USC Schaeffer Center and chair of the Department of Pharmaceutical and Health Economics at the USC Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences.

The findings also suggest that non-white people with dementia may be underdiagnosed for treatable symptoms of dementia, adding more evidence of racial and ethnic differences in dementia diagnosis and care. Previous USC Schaeffer Center research, for example, suggests that Blacks and Hispanics with dementia were more likely to have late or no diagnoses.

“We’re finding high levels of diagnoses of behavioral symptoms and use of drugs among these groups who are potentially vulnerable to these types of negative side effects,” said Thunell. “There are certainly benefits to getting a diagnosis so that you can get some form of treatment – even if it’s non-pharmacological – and we aren’t seeing as high of rates of diagnoses in non-white people. This could present challenges for persons with dementia and their caregivers.”

About the study

In addition to Thunell, Joyce and Zissimopoulos, the study was co-authored by Patricia M. Ferido, Schaeffer Center senior research programmer; Yi Chen, postdoctoral research fellow at Rush University Alzheimer’s Disease Center; Jenny S. Guadamuz, assistant professor at UC Berkeley School of Public Health; and Dima M. Qato, Schaeffer Center senior fellow.

This study was funded by the National Institutes of Health (Grants R01AG055401, P30AG066589).

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

You must be logged in to post a comment.