When a patient seeks care at an in-network facility but unintentionally is treated by an out-of-network provider they may receive a surprise medical bill. This type of billing is common, resulting in significant financial challenges for patients as well as contributing to increased overall healthcare spending.

While policymakers agree patients should be protected from this practice, debate has centered over how to decide what amount insurers should be required to pay providers for the unexpected out-of-network service. One solution, which was ultimately included in the federal bill that passed last month, includes arbitration to resolve payment disputes between the insurer and out-of-network provider.

A new analysis published in the January 2021 issue of Health Affairs examines how arbitration decisions compare to other provider payments in New Jersey, which passed surprise billing protections in 2018. The researchers find arbitrators seemed to anchor their decision to the 80th percentile of charges—an extremely high amount that is set by providers and detached from market forces. This aspect ultimately results in a system generous to providers and increases healthcare costs.

“We need to understand how arbitration to resolve out-of-network billing disputes is working in practice,” said Erin Trish, associate director of the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics and senior author on the study. “It is important to protect patients, but we also need to avoid a solution that provides perverse incentives and ultimately increases spending.”

Arbitration Used Infrequently, But Costly

Trish and her colleagues evaluated 1,695 cases that resulted in arbitration decisions in New Jersey in 2019. The researchers link administrative data from New Jersey arbitration cases to Medicare and commercial insurance claims data.

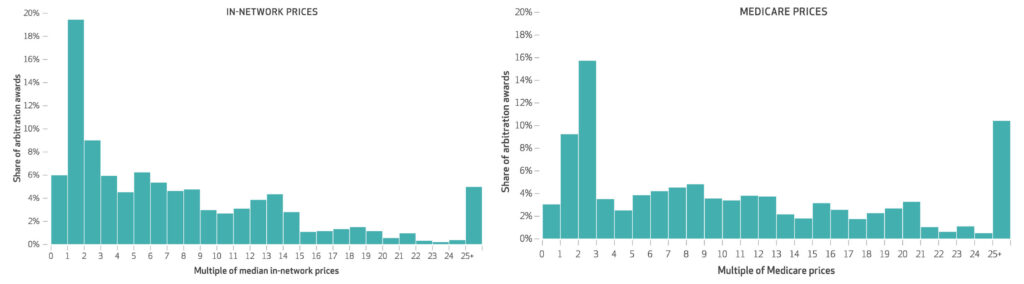

While relatively few cases resulted in arbitration, the award amounts were considerably higher than typical in-network payment amounts, according to the study. The mean arbitration award was $7,222— an amount 9 times higher than the median in-network price for the same services. The median award amount was 5.7 times higher at $4,354.

Thirty-one percent of cases decided were for amounts more than 10 times the median in-network price.

Compared to Medicare prices, which are lower than commercial prices, the mean and median arbitration awards were found to be 12.8 and 8.5 times higher, respectively.

Arbitrators Anchored Decisions to Provider Charges

In a final-offer arbitration model, arbitrators must select either the insurer’s or the provider’s final offer and cannot choose an amount in the middle. While the New Jersey legislation says a number of parameters should inform the decision, in practice the researchers found that arbitrators were shown the 80th, 90th, and 95th percentiles of both charges and allowed amounts and ultimately anchored their decisions to the 80th percentile of charges.

“When we examined the outcomes of cases and found that arbitrators were anchoring decisions based on the information they had available, it became clear that the intricacies of the process meaningfully impact how disputes are resolved,” explained Benjamin Chartock, a PhD student at the University of Pennsylvania and lead author of the study.

Specifically, the mean arbitration decision in their sample was 107% of the 80th percentile of billed charges for the same set of services.

“Basing arbitration decisions on an inflated list price, and the 80th percentile at that, is a surefire way to increase healthcare costs,” said Loren Adler, associate director of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy and coauthor of the study.

If relying on arbitration, the authors argue that arbitrators should be prohibited from considering provider charges and instead be equipped with information about commercial in-network prices and Medicare payment rates for the services under dispute.

What This Means for the Recent Federal Legislation

The federal law that passed in December 2020 uses arbitration, but decisions are to be based primarily on average in-network prices for the services in dispute. It bars the use of physician and hospital billed charges during arbitration, but does include a couple of provider-friendly criteria. The results of this study show that policymakers and administrators of the new bill will need to pay particular attention to the details when implementing the arbitration system.

“While state laws will supersede the federal protection for the health plans they regulate, states such as New Jersey that instruct arbitrators to consider provider charges should strongly consider adopting the more consumer-friendly version of arbitration established in the federal law for their entire state,” said Adler. “Such a decision could result in substantial savings for state residents and avoid the bureaucratic nightmare of two parallel arbitration systems running in a state.”

Additional coauthors on the study include Bich Ly and Erin Duffy, both of the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. This work was supported in part by a grant from Arnold Ventures.

You must be logged in to post a comment.