USC Schaeffer study finds the program’s oversight needs tightening to ensure discounts reach the right safety-net providers and patients

The federal 340B Drug Pricing Program strives to ease the burden of rising prescription drug costs by arranging for discount pricing for outpatient drugs to certain public and nonprofit hospitals and other safety net healthcare providers. Although the program enjoys bipartisan support, many question whether the use of 340B funding aligns with the program’s aims to benefit vulnerable, low-income patients. Discounted purchases made through the program have increased from about $4 billion per year in 2007-09 to $38 billion in 2020—an increase that corresponds with significant expansions of the program.

“The program was formed to help healthcare providers stretch limited resources to better meet the needs of patients who have been historically under resourced,” says USC Schaeffer Fellow Karen Mulligan. “But the program has grown significantly with little oversight.” Mulligan is an assistant research professor at the USC Price School of Public Policy.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

A new white paper by Mulligan provides historic context and puts the pitfalls and promise of 340B into perspective. Her analysis also suggests how the program can be modified to better serve its aims of stretching federal dollars to better serve patients in need.

Covered Entities and Growth

Established in 1992 and administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), 340B allows eligible clinics and hospitals—known as “covered entities”—to buy outpatient medications at a 20–50% discount. The program does not cover vaccines and has strict stipulations for orphan drugs for rare diseases.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers must participate as a condition of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, which helps cover the costs of many outpatient prescriptions for beneficiaries. “This makes the 340B program uncommon among federal laws,” according to Mulligan, because it mandates a transfer of resources from one group of private entities (drug manufacturers and wholesalers) to another (healthcare providers).

“Even so,” she adds, “drug companies make up for those discounts in terms of the sheer volume of covered sales.” In 2020 alone, total sales of 340B-discounted drugs accounted for about $38 billion—almost 7% of the total U.S. drug market.

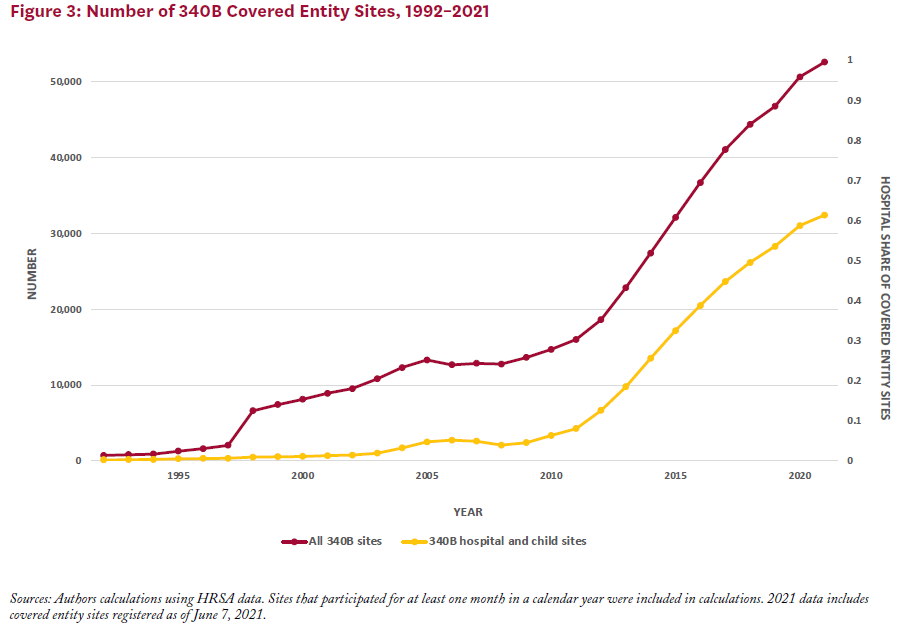

That amount is only expected to grow, Mulligan adds. Between 2000 and 2020, the number of covered entity sites ballooned from just over 8,100 to 50,000. Hospitals account for more than 60% of this total. Participation has also risen dramatically among contract pharmacies and disproportionate share hospitals—the latter so-named because of the large number of low-income Medicare or Medicaid patients they serve.

Program Challenges—Drug Diversion and Duplicate Discounts

With its dramatic growth, the 340B program has manifested growing challenges. For example, the only qualification patients need to receive drugs purchased with 340B discounts is a record of receiving care from the covered entity. So-called “drug diversion” occurs when drugs purchased with 340B discounts are given to an ineligible patient—such as one treated by a doctor not employed by the covered entity. Hospitals and contract pharmacies face a higher risk of such diversion because of the wide range of eligible and ineligible patients they serve. “To prevent drug diversion, covered entities can either separate their inventories of drugs bought with 340B discounts or track their stock virtually,” Mulligan suggests.

Another challenge is eliminating duplicate discounts, which occur when manufacturers provide 340B discounts while simultaneously honoring state Medicaid rebates for the same drug. While the full extent of these duplications is unknown, the 1,536 audits conducted by the HRSA between 2012 and 2019 revealed 429 incidents.

“This is another issue that could be cleared up with better tracking and recordkeeping,” Mulligan says.

Perspectives on Reform

The biggest roadblock to enhancing 340B is HRSA’s limited enforcement authority. Political discord is another hurdle, Mulligan notes, citing the fact that none of the more than 50 proposed improvements offered by Congress over the past decade have passed into law.

“But the 340B program needs modification to fulfill its ideals and ensure future sustainability,” she says. “Its continued growth, combined with limited oversight, has created challenges for many small safety-net clinics. Meanwhile, terms guiding the transfer of billions in value every year are left up to private companies and the courts with little guidance from HRSA, which partly stems from their limited regulatory authority.”

Mulligan suggests future legislation to strengthen the agency’s regulatory powers and tighten the program’s vague language that manufacturers and hospitals use to push the program’s boundaries. There also may be opportunities for the private sector to provide solutions to counter drug diversion and duplicate discounts.

“There are valid concerns with the 340B program related to transparency, diversion and duplicate discounts, particularly through contract pharmacies and hospitals,” she writes. “However, the 340B program has also provided significant resources to many providers and allowed them to better serve millions of patients.”

Support for this work was provided by the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Schaeffer Center is supported by unrestricted donations from a variety of public and private entities, including pharmaceutical manufacturers and healthcare providers who participate in the 340B program. These are listed in our annual report which can be found on our website.

You must be logged in to post a comment.