Editor’s Note: This perspective was originally published on Health Affairs Forefront on May 4, 2023.

Medicare drug price negotiation is almost upon us. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) mandates that the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) implement a maximum fair price (MFP) for drug price negotiation beginning in 2026. How should CMS implement such a program given such a short timeline? We recommend a three-step approach to implementing the MFP that moves toward a drug pricing paradigm based on treatment value.

CMS’s challenge

Well-functioning markets for branded prescription drugs or biologics reward innovative products that are valuable to patients and their families while penalizing those that are not. Well-functioning markets for generic prescription drugs and biosimilars drive down prices toward marginal cost after a suitable period of patent protection. IRA implementation ought to aim for these same goals: Stimulate valuable innovation, discourage low-value drugs, and drive down long-run costs. However, CMS faces statutory and practical constraints. Its approach must be feasible to implement; based on comparative effectiveness, according to statute; and non-discriminatory in its treatment of the aged and of people with disabilities or terminal illness.

Per the timeline, CMS must identify 10 Medicare Part D drugs to be covered under the MFP negotiations by September 1, 2023, followed by initial offers of the MFP for each selected drug by February 1, 2024. The final negotiated prices are to go into effect on January 1, 2026. While the IRA’s initial MFP negotiation is limited to 10 drugs, the number of drugs covered under the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program will expand over time. Hence, it is vital that CMS get drug pricing right.

Drug pricing options: making the case for value-based pricing

The IRA requires that CMS consider three critical factors when setting MFPs:

- comparative effectiveness of the drug (Section 1194(e)(2)(C)), including whether the drug represents a therapeutic advance or satisfies and unmet need (Section 1194(e)(2)(A), (D));

- the costs of research and development (R&D), production and distribution of the drug (Section 1194(e)(1)(A)-(B)), including prior federal support for R&D for that drug (Section 1194(e)(1)(C)); and

- drug price and sales (Section 1194(e)(1)(E)), including generic competition for the drug (Section 1194(e)(1)(D).

While the statute mandates that CMS consider these various factors, it remains silent on which, if any, should play the most significant role in quantifying MFP.

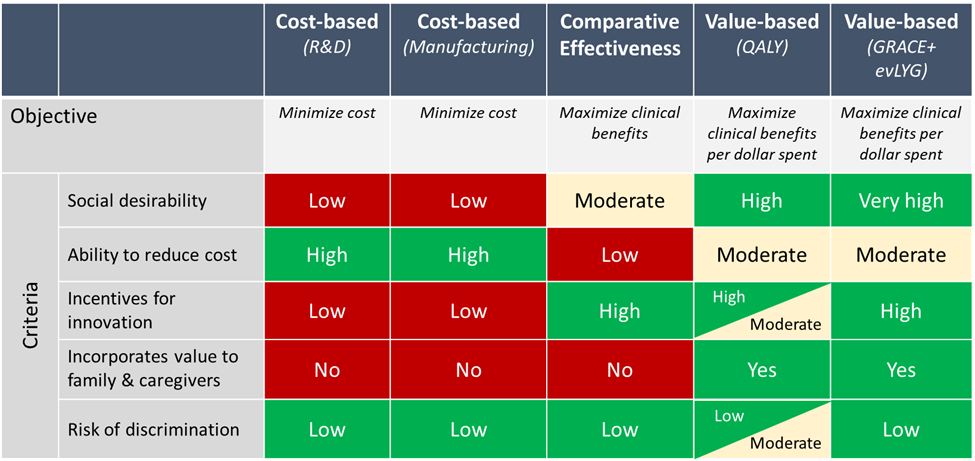

When setting MFP, therefore, CMS could potentially rely on: costs, stopping short of effectiveness; comparative clinical effectiveness, stopping short of quantifying economic value; or translating comparative clinical effectiveness into value to patients (see exhibit 1). We consider each in turn and make the case for a focus on value.

Cost-based approaches may appeal to regulators struggling with Medicare cost growth, and CMS is required by law to consider some dimensions of cost, including the total budget impact on Medicare and a company’s R&D costs. However, focusing primarily on costs will lead the agency into a thicket of implementation challenges and perverse incentives for industry. Cost-based approaches reward manufacturers that fail to contain manufacturing or R&D costs. Moreover, reimbursement based on manufacturing and (molecule-specific) R&D costs alone would ignore R&D costs for the nearly nine out of 10 products that fail in clinical trials. The costs of failure are difficult to trace back to a particular drug in the market, but they are nonetheless real contributors to overall drug development costs.

The IRA’s stipulation that CMS use comparative clinical effectiveness is a step in the right direction but only a partial solution. Comparative effectiveness identifies which treatment is clinically superior for a given condition. Research suggests that 81 percent of the time treatments that are comparatively effective are also cost-effective. However, linking comparative effectiveness to prices is challenging. The IRA requires that CMS set prices for drugs that treat vastly different conditions, but comparative effectiveness alone provides little or no guidance when it comes to negotiating appropriate prices across these conditions. Consider a cancer drug that increases survival by six months alongside another drug for relapsed multiple sclerosis that extends a patient’s mobility by a decade or more. CMS must decide which merits a higher price but will lack a means for comparing clinical effectiveness across such distinct diseases. Failure to consider different diseases alongside each other locks in existing pricing inefficiencies.

The solution we recommend is to measure a technology’s value in terms of health improvements to patients and then use this quantity to set MFP. Value-based metrics fall under the rubric of cost-effectiveness analysis as opposed to comparative effectiveness analysis. Cost-effectiveness analysis, which is grounded in the value of health defined as freedom from multiple diseases, addresses the condition-specific limitation of comparative effectiveness. It has the additional advantage of balancing considerations of effectiveness with costs, as required by the IRA.

In the past, advocates for people with disabilities, terminal illness, and other severe disease have objected to traditional economic methods for quantifying value, in particular the use of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). Conventional methods of cost-effectiveness analysis that treat life-years gained as less valuable when they accrue in sicker and more disabled patients are prohibited under the IRA and considered by some to be unethical.

Fortunately, scientifically validated techniques now exist that would enable CMS to quantify value without violating the IRA ban. The equal value of life-year gained (evLYG) measure treats people with and without disability equally when calculating the value of life extension. The more recently introduced Generalized Risk-Adjusted Cost Effectiveness (GRACE) approach goes even further: GRACE implies that treatments should be valued more, not just the same, for people with disabilities or severe illness. Together, GRACE and evLYG could help CMS reach its goal of promoting equity. CMS could set prices based on GRACE combined with evLYG to ensure individuals with disabilities are not discriminated against. For instance, CMS could begin drug price negotiations with the MFP set at the price generated by GRACE under the evLYG assumption.

Exhibit 1: Illustrative comparison of different approaches for CMS to set a maximum fair price

Image: Health Affairs

Source: Illustrative evaluation based on author opinion.

Notes: evLYG is equal value of life year gained. GRACE is generalized risk-adjusted cost-effectiveness. QALY is quality-adjusted life year. R&D is research and development. Low/Moderate/High refer to the potential of each criterion to achieve the objective.

Why CMS needs value-based pricing using the gRACE methodology

Value-based pricing—particularly when implemented using the GRACE methodology combined with evLYG—meets CMS’s needs.

- It is transparent and systematic;

- It permits principled treatment of drugs for different conditions;

- It considers both effectiveness and costs;

- It assigns at least as much and typically more value to drugs that improve the health and well-being of people with disabilities, severe illness, and terminal illness;

- It promises to lower spending on treatments for less debilitating illness, and on treatments whose prices exceed their value to patients;

- It moves beyond the standard unadjusted QALY measure and the toxic political dialogue that has surrounded it;

- It provides a single framework that can be adapted to meet CMS’s changing needs; and

- It incentivizes and rewards innovation.

Using GRACE plus evLYG provides a foundation for value assessment consistent with the IRA’s statutory requirements. When considering comparative effectiveness, CMS is prohibited from treating a quantum of life extension for an elderly, disabled, or terminally ill individual as “of lower value” than that for a younger, non-disabled, or not terminally ill person. The non-discrimination principle in the statutory text allows valuation of life extension so long as extensions for vulnerable populations are valued at least as much as for other persons. CMS, in a March 15, 2023, memo soliciting comments on the Medicare Drug Price Negotiation Program, interprets the non-discrimination principle exactly this way (p. 36).

Using GRACE plus evLYG combines the aforementioned three critical factors CMS must consider in a principled manner to comply with the statute’s non-discrimination principle. The only tension between these methods and the CMS memo (p. 50) is that the latter states that “CMS intends to use a qualitative approach to preserve flexibility in negotiation.” We recommend that qualitative analysis be restricted to those considerations that have not been quantified through prior study. Applying a pre-specified quantitative approach to the remaining considerations makes the price negotiation process more transparent and predictable for both patient groups and manufacturers.

Recommended three-step approach

While CMS has a short time frame to implement setting maximum fair drug prices, we recommend a three-step approach.

Step 1: Leverage Manufacturer Submissions To Set Maximum Fair Prices Based On Transparent Methods

To reduce the burden on the agency, we recommend that CMS begin with detailed and specific requests for information from manufacturers, from which it can distill a set of acceptable value elements into an MFP determination. For example, CMS could require manufacturers to submit comparative clinical effectiveness and projected value based on GRACE plus evLYG, at a minimum. In addition, CMS could specify that manufacturers assess other dimensions of value, perhaps disease-specific, based on published methods in the field of health care value assessment. For instance, the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research (ISPOR) Task Force on Value Frameworks developed a “value flower” that enumerates a range of different value elements relevant to patients and society, and the Second Panel on Cost-Effectiveness in Health and Medicine articulated best practices for measuring value of health interventions to society. CMS could require manufacturers to submit assessments of value according to each of the value elements identified in these prior studies.

Step 2: seek feedback from key stakeholders on how to refine determination of value-based prices

In parallel with the submission of material from manufacturers, CMS should seek feedback from patients, health care providers, economists, epidemiologists, and others regarding how best to implement value-based MFP measurement. At the conclusion of this stakeholder engagement process, CMS is likely to have many of the requisite analytical inputs to implement value-based pricing themselves based on GRACE and evLYG, and other value elements of interest. Nonetheless, the stakeholder engagement process may identify additional elements of value for inclusion.

Step 3: periodically Refine The Transparent Methods Used For Determining Maximum Fair Prices

Finally, the MFP determination process should be updated, with improvements to the methodology over time. In particular, CMS should consider not only value to patients in terms of health benefits but also value to caregivers, employers, and broader society as well as how new medicines reduce or exacerbate health disparities.

CMS should align pricing with value

The Medicare Drug Price Negotiation program should set MFP based on value. We propose a feasible, three-step process for CMS to implement such a proposal. In parallel, CMS should consider ways to advance value assessment for use in setting MFP for selected drugs. For instance, value-based pricing could allow a drug’s MFP to vary depending on the disease it treats (that is, indication-specific pricing) or refine how to incorporate value to caregivers and other stakeholders. The pharmaceutical industry is a multinational and global enterprise, and CMS must recognize that prices set in the US may also impact prices in other countries as well. To make sure that CMS is getting its money’s worth for today’s drugs, it must ensure that MFP is aligned to drug value.

Authors’ Note

Jason Shafrin is an employee of FTI Consulting, a consulting firm to a variety of health care, life sciences, and other industries, including government and non-governmental organizations. The views expressed herein are those of the author and not necessarily the views of FTI Consulting, Inc., its management, its subsidiaries, its affiliates, or its other professionals. Darius Lakdawalla in the past three years has received speaker fees, travel assistance, or consulting income from the following sources: Amgen, Genentech, Gilead, GRAIL, Mylan, Novartis, Otsuka, Perrigo, Pfizer, and Sorrento Therapeutics. Dr. Lakdawalla also owns equity in Precision Medicine Group, for which he previously served as a consultant. He is also co-founder and chief scientific officer of EntityRisk, Inc., which develops software and analytic tools for use by health care firms. Jalpa Doshi reports serving as a consultant and/or receiving grants from biopharmaceutical companies, insurers, and foundations. In the recent past, Lou Garrison has done consulting work with a number of organizations with an interest in these issues, including PhRMA, the Office of Health Economics, Pfizer, Eli Lilly, Gilead, Genentech, MSD, Boehringer Ingelheim, BioMarin, GSK, and Novartis Gene Therapy. Anup Malani acknowledges the support of the Samuel J. Kersten Faculty Fund at the University of Chicago Law School. In the past three years, Malani has received consulting income from the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank, IDFC Institute, the Miller Center at the University of Virginia, Compass Lexecon, Intensity, LLC, Keystone Strategy, Brattle Group, and Cornerstone Research. Peter Neumann is a member of the Center for the Evaluation of Value and Risk in Health at the Institute for Clinical Research and Health Policy Studies at Tufts Medical Center. The center receives funding from government, private foundation, and pharmaceutical industry sources. Dr. Neumann has consulted with pharmaceutical companies on issues related to health economics and outcomes research. Charles Phelps is currently a consultant to Entity Risk, the Office of Health Economics (London, UK), Pfizer, and he served as part of IVI’s MCDA Working Group. In the past five years, he has also consulted with Audentes Therapeutics and Merck. Adrian Towse has received personal consulting fees from pharmaceutical, vaccine, and diagnostic companies; and the Office of Health Economics receives consulting fee income from pharmaceutical, vaccine, and diagnostic companies. Richard Willke has served on advisory boards and as a consultant on projects sponsored by biopharmaceutical companies.

Shafrin, J., Lakdawalla, D. N., Doshi, J. A., Garrison Jr, L. P., Malani, A., Neumann, P. J., … & Willke, R. J. (2023). A Strategy For Value-Based Drug Pricing Under The Inflation Reduction Act. Health Affairs Forefront.

10.1377/forefront.20230503.153705

Copyright © [2023] Health Affairs by Project HOPE – The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news