Editor’s note: This analysis is part of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, which is a partnership between the Center for Health Policy at Brookings and the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings.

Stability has long been an issue for the individual health insurance market, even before the Affordable Care Act. While reforms adopted under the ACA initially succeeded in addressing some of these market issues, market conditions substantially worsened in 2016.

Insurers exited the individual market, both on and off the subsidized exchanges, leaving many areas with only a single insurer, and threatening to leave some areas (mostly rural) with no insurer on the exchange. Most insurers suffered significant losses in the individual market the first three years under the ACA, leading to very substantial increases in premiums a couple of years in a row.

For a time, it appeared that rate increases in 2016 and 2017 would be sufficient to stabilize the market by returning insurers to profitability, which would bring future increases in line with normal medical cost trends. However, Congress’s decision to repeal the individual mandate and the Trump Administration’s decision to halt “cost-sharing reduction” payments to insurers, along with other measures that were seen as destabilizing, created substantial new uncertainty for market conditions in 2018.

This uncertainty continues into 2019, owing both to lack of clarity on the actual effects of last year’s statutory and regulatory changes, and to pending regulatory changes that would expand the availability of “non-compliant” plans sold outside of the ACA-regulated market. These uncertainties further complicate insurers’ decisions about whether to remain in the individual market and how much to increase premiums.

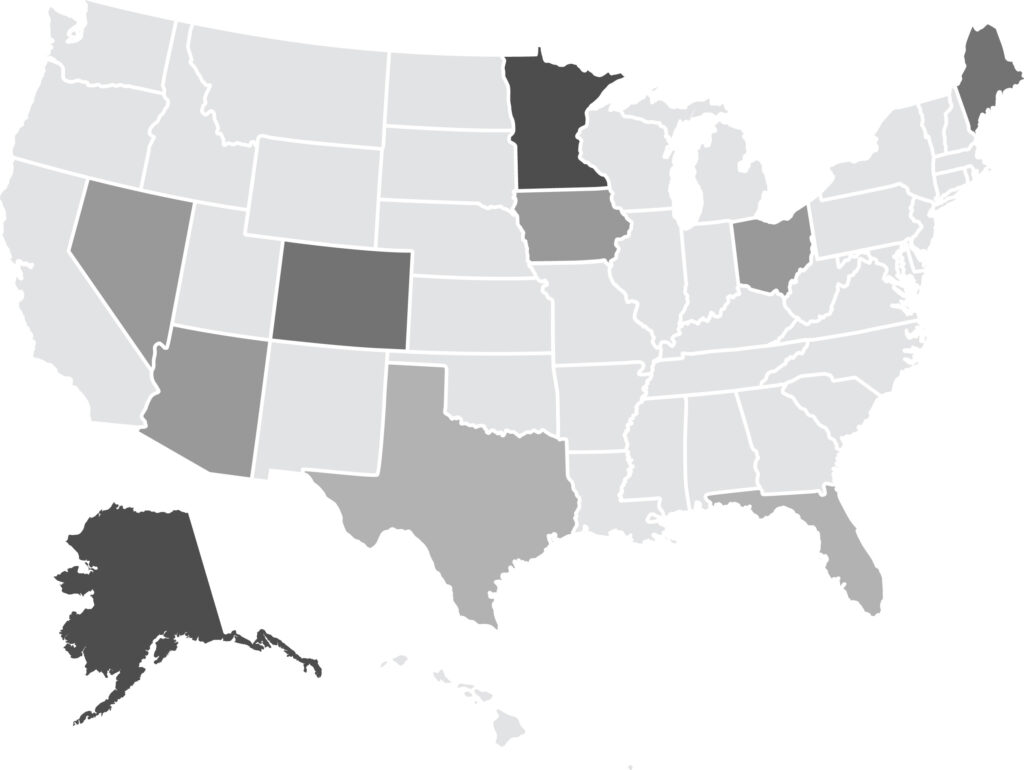

In “Stabilizing and Strengthening the Individual Health Insurance Market: A View from Ten States,” Mark Hall examines the causes of instability in the individual market and identifies measures to help improve stability based off of interviews with key stakeholders in 10 states.

The Condition of the Individual Market

In the states studied—Alaska, Arizona, Colorado, Florida, Iowa, Maine, Minnesota, Nevada, Ohio, and Texas—opinions about market stability vary widely across states and stakeholders.

While enrollment has remained remarkably strong in the ACA’s subsidized exchanges, enrollment by people not receiving subsidies has dropped sharply.

States that operate their own exchanges have had somewhat stronger enrollment (both on and off the exchanges), and lower premiums, than states using the federal exchange.

A core of insurers remain committed to the individual market because enrollment remains substantial, and most insurers have been able to increase prices enough to become profitable. Some insurers that previously left or stayed out of markets now appear to be (re)entering.

Political Uncertainty

Premiums have increased sharply over the past two to three years, initially because insurers had underpriced relative to the actual claims costs that ACA enrollees generated. However, political uncertainty in recent years caused some insurers to leave the market and those who stayed raised their rates.

Insurers were able to cope with the Trump administration’s halt to CSR payments by increasing their rates for 2018 while the dominant view in most states is that the adverse effects of the repeal of the individual mandate will be less than originally thought. Even if the mandate is not essential, many subjects viewed it as helpful to market stability. Thus, there is some interest in replacing the federal mandate with alternative measures.

Because most insurers have become profitable in the individual market, future rate increases are likely to be closer to general medical cost trends (which are in the single digits). But this moderation may not hold if additional adverse regulatory or policy changes are made, and some such changes have been recently announced.

Actions to Restore Stability

Many subjects viewed reinsurance as potentially helpful to market conditions, but only modestly so because funding levels typically proposed produce just a one-time lessening of rate increases in the range of 10-20 percent. Some subjects thought that a better use of additional funding would be to expand the range of people who are eligible for premium subsidies.

Concerns were expressed about coverage options that do not comply with ACA regulations, such as sharing ministries, association health plans, and short-term plans. However, some thought this outweighed harms to the ACA-compliant market; thus, there was some support for allowing separate markets (ACA and non-ACA) to develop, especially in states where unsubsidized prices are already particularly high.

Other federal measures, such as tightening up special enrollment, more flexibility in covered benefits, and lower medical loss ratios, were not seen as having a notable effect on market stability.

Measures that states might consider (in addition to those noted above) include: Medicaid buy-in as a “public option”; assessing non-complying plans to fund expanded ACA subsidies; investing more in marketing and outreach; “auto-enrollment” in “zero premium” Bronze plans; and allowing insurers to make mid-year rate corrections to account for major new regulatory changes.

Conclusion

The ACA’s individual market is in generally the same shape now as it was at the end of 2016. Prices are high and insurer participation is down, but these conditions are not fundamentally worse than they were at the end of the Obama administration. For a variety of reasons, the ACA’s core market has withstood remarkably well the various body blows it absorbed during 2017, including repeal of the individual mandate, and halting payments to insurers for reduced cost sharing by low-income subscribers.

The measures currently available to states are unlikely, however, to improve the individual market to the extent that is needed. Although the ACA market is likely to survive in its basic current form, the future health of the market—especially for unsubsidized people—depends on the willingness and ability of federal lawmakers to muster the political determination to make substantial improvements.