More than 10 million American adults suffer from serious mental illnesses, including major depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Medicaid, the state-federal health program for low-income people, is the nation’s largest funding source of mental health treatment, including prescription drugs. Access to effective medication often can mean the difference between a mentally ill person living safely in the community or landing on the streets, in jail or dead. But psychiatric drugs are expensive, and state Medicaid programs face constant pressure to contain costs. Many states have restricted access to psychiatric drugs in hopes of saving money.

However, research from the USC Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics shows that Medicaid formulary restrictions, such as prior authorization and step therapy—where patients must first try less expensive drugs—save little, if any, money on drug spending. Instead, formulary restrictions increase overall Medicaid spending for people with serious mental illnesses, especially for inpatient hospital care. Beyond the human toll of mentally ill people’s increased likelihood of hospitalization, homelessness and incarceration, formulary restrictions also raise costs to society through increased spending to jail mentally ill Americans. One study, for example, found that Medicaid formulary restrictions on atypical anti-psychotics for patients with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder increase state costs by an estimated $1 billion annually when factoring in both extra Medicaid spending and increased incarceration rates.

State Budgets, Medicaid Formulary Restrictions and Patient Health

Faced with rapidly growing prescription drug spending, many state Medicaid programs have adopted drug formularies—or lists of preferred drugs—that restrict access to medications to treat serious mental illnesses, including major depression, schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Common Medicaid formulary restrictions include:

- prior authorization, which requires clinicians to obtain permission from Medicaid to prescribe a specified drug, or Medicaid will not guarantee reimbursement; and

- step therapy, which permits payment for a non-preferred medication only after the patient tries other selected medications—usually cheaper alternatives.

Under both policies, clinicians must make the case for why patients need non-preferred drugs. Step therapy, in particular, restricts clinical decision making by requiring the use of certain medications first even if the clinician believes the preferred drugs are less desirable— for example, because of lower tolerability, therapeutic noncompliance from adverse side effects, poor treatment outcomes or lack of improvement compared to non- preferred medications.

Growing evidence, however, indicates that Medicaid formulary restrictions save little, if any, money on drug spending for serious mental illnesses and instead contribute to worse patient outcomes, higher overall Medicaid spending, and increased incarceration rates for people with serious mental illnesses.

This Issue Brief summarizes three recent peer-reviewed studies by Schaeffer Center researchers published in the Forum for Health Economics and Policy and the American Journal of Managed Care that examined Medicaid formulary restrictions for psychiatric medications, Medicaid spending and estimated costs of increased incarceration rates for people with serious mental illnesses (see Data Source).

Prior Authorization/ Step Therapy and Major Depression

An estimated one in five adults covered by Medicaid is diagnosed with major depressive disorder (MDD), a severe and debilitating form of depression that impairs people’s ability to function—for example, staying employed and interacting with other people—without proper treatment, including antidepressants. Medicaid spending on patients with MDD has grown rapidly from $159 million in 1991 to almost $2 billion in 2005, making it an attractive cost-containment target.

To examine the relationship between Medicaid formulary restrictions on anti- depressants and health care utilization and spending, Schaeffer Center researchers used medical and pharmacy claims from 24 state Medicaid programs to identify acute-care utilization—hospitalizations and emergency department (ED) visits—and spending for 901,376 patients diagnosed with major depressive disorder between 2001 and 2008. Researchers then linked these data to formulary restrictions—prior authorization and step therapy—on antidepressants in the 24 states during the same period and examined the financial effects of prior authorization alone and prior authorization combined with step therapy.

Over the course of the study period, the proportion of patients in the study sample exposed to prior authorization for at least one antidepressant increased from 40 percent to 80 percent. The use of step therapy combined with prior authorization was not observed in the study sample until 2003 but increased to about 20 percent of patients by 2008.

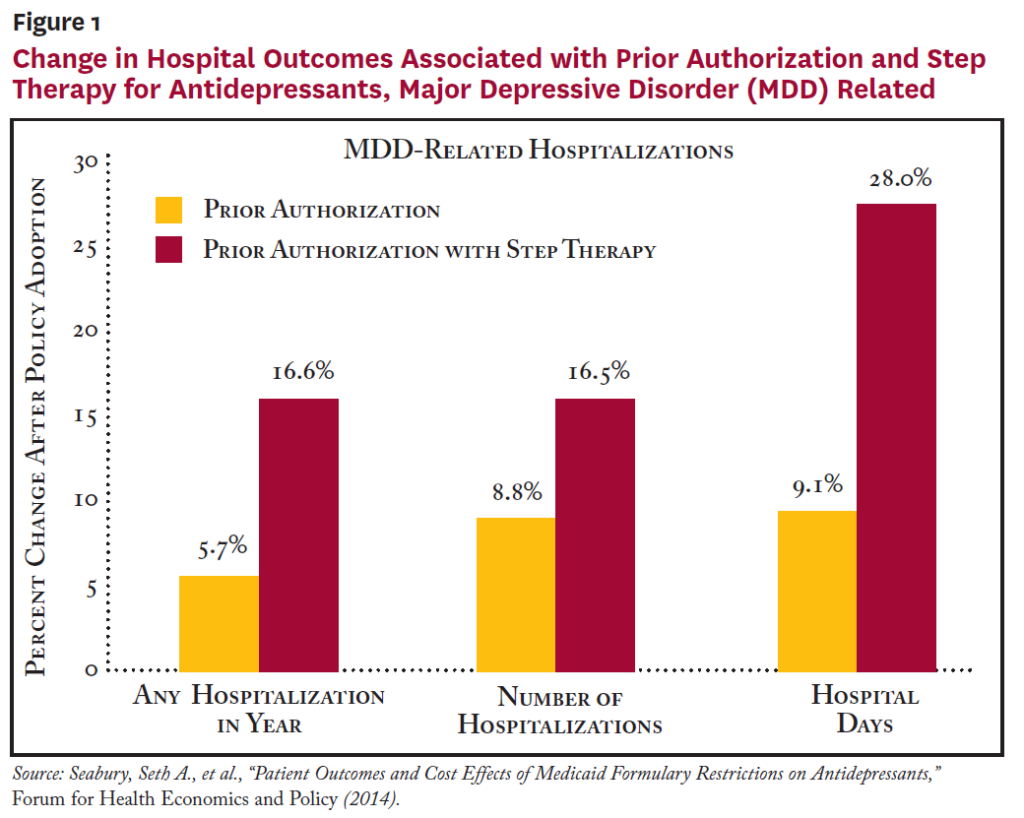

After controlling for differences in patient and state characteristics, researchers compared outcomes for Medicaid patients in states with and without formulary restrictions before and after restrictions were adopted. Restricting access to antidepressants through both prior authorization and step therapy was associated with a 2.1 percentage point (8.2%) increase in the likelihood of any hospitalization and a 1.7 percentage point (16.6%) increase in the likelihood of an MDD-related hospitalization (see Figure 1).While there were significant associations between formulary restrictions on antidepressants and hospitalizations, there appeared to be little relationship between formulary restrictions and ED visits or physician office visits.

On the spending side, researchers found no evidence of any overall savings to Medicaid programs from formulary restrictions on antidepressants. The combination of prior authorization and step therapy showed a statistically significant association with higher inpatient spending, while prior authorization alone showed a statistically significant association with higher outpatient expenditures. At the same time, there was no indication that prior authorization resulted in significantly lower pharmacy spending. Considering pharmacy and non-pharmacy medical spending together, formulary restrictions were not associated with any statistically significant change in overall Medicaid spending per MDD patient, but patients with MDD were put at significantly higher risk of hospitalizations.

Atypical Antipsychotics and Formulary Restrictions

The introduction of atypical antipsychotics—also known as second-generation antipsychotics—almost three decades ago signaled a significant advance in treatment for people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Compared to first-generation antipsychotics, the newer drugs are less likely to cause side effects that threaten patient adherence, such as significant movement disorders and heavy sedation.

Atypical antipsychotics accounted for more than 15 percent of all Medicaid spending in 2005 and are among the most frequently targeted drugs for Medicaid formulary restrictions. Previous research has shown that while atypical antipsychotics are generally effective, patients respond differently to specific atypical antipsychotic medications, often requiring changes in treatment regimens to attain desired clinical outcomes. As a result, formulary restrictions on atypical antipsychotics can disrupt treatment and affect patient adherence. While previous research has found that formulary restrictions on atypical antipsychotics diminish patient adherence and raise health care spending, most of the studies have focused on a small group of states.

To provide a more complete picture of potential unintended consequences of trying to contain costs by curtailing access to atypical antipsychotics, Schaeffer Center researchers used medical and pharmacy claims for people with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder from 24 state Medicaid programs between 2001 and 2008 to estimate the impact of formulary restrictions on health care spending.

The study included 117, 908 patients with schizophrenia and 170,596 people with bipolar disorder who were newly prescribed one of five atypical antipsychotics—olanzapine, risperidone, quetiapine, aripiprazole or ziprasidone. The formulary restrictions examined were prior authorization, step therapy and quantity limits. Similar to state trends with antidepressants, Medicaid formulary restrictions on atypical antipsychotics grew quickly between 2001 and 2008.

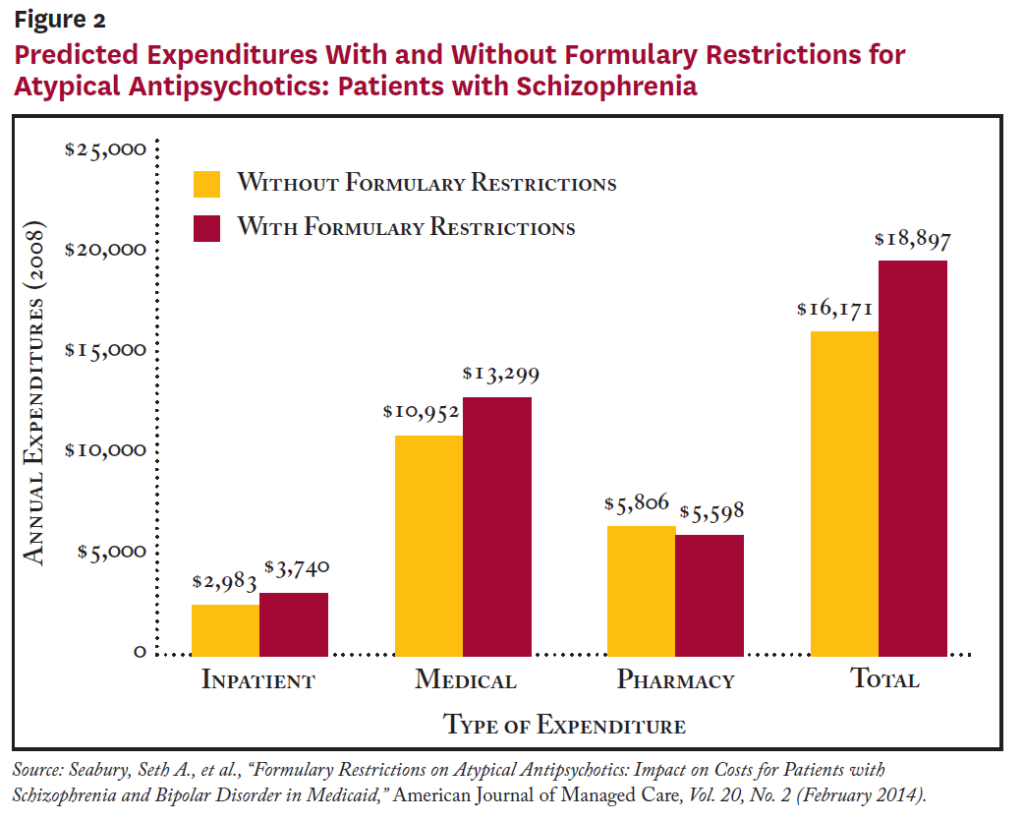

According to the study, patients with schizophrenia subject to formulary restrictions were more likely to experience a hospitalization, had 23 percent higher inpatient costs and had 16 percent higher total medical costs (see Figure 2). Similar results were found for patients with bipolar disorder, with those subject to formulary restrictions being more likely to be hospitalized and 20 percent higher inpatient costs and 10 percent higher total costs.

Formulary restrictions were not associated with statistically significantly lower pharmacy expenditures for either group. Additionally, patients with schizophrenia subject to formulary restrictions had worse adherence, while formulary restrictions had no significant effect on bipolar patients’ adherence.

Jail: The New Hospital Bed?

About 36 percent of men and 28 percent of women with serious mental illness in the United States went without treatment in 2013, according to the most recent U.S. Behavioral Health Barometer. And, each year, an estimated 356,000 Americans with serious mental illness end up in jail, another 200,000 are homeless, 108,000 are hospitalized and 34,000 die by suicide, according to a 2014 investigative series by USA Today.1

“We have replaced the hospital bed with the jail cell, the homeless shelter and the coffin,” U.S. Rep. Tim Murphy, R-Pa., told USA Today.

The number of inpatient psychiatric hospital beds has dropped dramatically since the 1950s when a move to deinstitutionalize care for people with serious mental illnesses led to many problem- plagued state mental hospitals closing. By one 2010 estimate, there was one psychiatric bed for every 300 Americans in 1955, dropping to one psychiatric bed for every 3,000 Americans in 2005.2 In many cases, promised community-based mental health treatment to replace inpatient beds never materialized, and state budget cuts have hit mental health services hard—an estimated $5 billion decrease between 2009 and 2012.3

Prior Authorization and Incarceration Rates

When people with schizophrenia miss or discontinue taking their medication, they are at high risk of an acute psychotic episode, which can lead to threatening behavior, contact with law enforcement, arrest and incarceration.

To examine the impact of formulary restrictions on the likelihood that people with schizophrenia will be arrested and incarcerated, Schaeffer Center researchers looked at drug-level information on prior authorization policies in 30 state Medicaid programs, state usage rates of atypical antipsychotics and responses from 16,844 inmates to a nationally representative survey that included detailed information about any mental health conditions.

The analysis found that people with schizophrenia in states with prior authorization for atypical antipsychotics faced a 22 percent increase in the likelihood of imprisonment. Inmates in those states also were more likely to have been previously diagnosed with schizophrenia. And, the study found that higher state-level atypical prescriptions per capita were associated with lower likelihood of psychotic symptoms and prior schizophrenia diagnosis among prisoners. The bottom line: a strong link between Medicaid prior authorization requirements for atypical antipsychotics and higher rates of incarceration of mentally ill people.

As part of the study looking at broader formulary restrictions on atypical anti- psychotics, researchers estimated that the restrictions increased the number of prisoners by almost 10,000 and incarceration costs by $362 million nationwide in 2008. When researchers extrapolated the average increase in Medicaid spending for patients with schizophrenia and patients with bipolar disorder, combined with the additional prison costs, the total estimated cost to society of formulary restrictions on atypical antipsychotics exceeded $1 billion annually.

Policy Implications

Taken as a whole, the Schaeffer Center research findings related to Medicaid formulary restrictions on psychiatric drugs published in the Forum for Health Economics and Policy and the American Journal of Managed Care provide policymakers with important new information about the effectiveness of policies restricting access to medication for people with serious mental illnesses. Not only is it becoming clear that Medicaid formulary restrictions on antidepressants and atypical antipsychotics harm patients, they also likely drive up both medical and prison costs.

Formulary restrictions on psychiatric drugs are only one aspect of the mental health crisis in America. As policymakers re-evaluate Medicaid formulary restrictions, larger issues require their attention as well. A fundamental question that cannot go unanswered much longer is whether the criminal justice system will continue as the de facto solution to the millions of Americans with serious mental illness who don’t receive appropriate treatment.

Notes

- Szabo, Liz, “Cost of Not Caring: Mental Illness in America,” USA Today ( July 2014).

- Treatment Advocacy Center, Arlington, Va., and National Sheriffs’ Association, Arlington, Va., “More Mentally Ill Persons Are in Jails and Prisons Than Hospitals: A Survey of States” (May 2014).

- Szabo (2014).

Data Source

This Issue Brief summarizes three peer-reviewed studies conducted by researchers affiliated with the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics, with additional sup- port from external funders. The three articles are as follows:

- Seabury, Seth A., et al., “Patient Outcomes and Cost Effects of Medicaid Formulary Restrictions on Antidepressants,” Forum for Health Economics and Policy (2014).

- Seabury, Seth A., et al., “Formulary Restrictions on Atypical Antipsychotics: Impact on Costs for Patients with Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder in Medicaid,” American Journal of Managed Care, Vol. 20, No. 2 (February 2014).

- Goldman, Dana P., et al., “Medicaid Prior Authorization Policies and Imprisonment Among Patients with Schizophrenia,” American Journal of Managed Care, Vol. 20, No. 7 ( July 2014).

You must be logged in to post a comment.