Editor’s Note: This analysis is part of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, which is a partnership between Economic Studies at Brookings and the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national healthcare debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings.

Auto-enrollment into health insurance coverage is an attractive policy that can drive the U.S. health care system towards universal coverage. It appears in coverage expansion proposals put forward by 2020 presidential candidates, advocates, and scholars. These approaches are motivated by the fact that at any given time half of the uninsured are eligible for existing subsidized coverage programs. But a major challenge for any auto-enrollment proposal is coverage churn throughout the year: individuals become uninsured as their circumstances change, and those who were previously uninsured gain coverage.

One approach to address these challenges is to pursue retroactive enrollment into coverage, where all uninsured individuals would be considered covered and premiums charged retroactively, eliminating the need to know about status changes in real time. While this approach would achieve truly universal coverage, some may have concerns about requiring individuals to pay premiums for coverage they have not actively selected and therefore wish to explore less ambitious policies. One such alternative is a forward-looking tax-based auto-enrollment policy under which uninsured consumers eligible for $0 premium coverage would be automatically enrolled after filing their taxes each year.

The analysis presented here briefly describes how prospective tax-based auto-enrollment could work and considers some of the major policy and operational changes necessary to implement the policy described. It then uses survey data to assess how effective an optimally-executed version of this policy would be in targeting the uninsured.

How it operates: On the individual tax return, tax filers would indicate whether each member of their household had coverage as of the date of filing (e.g., April 15). The income reported on the tax return would be used to determine if uninsured household members were eligible for Medicaid, for Marketplace coverage with sufficient financial assistance that they could obtain a plan for $0, or only for coverage that charged a premium. Those eligible for Medicaid or for $0 Marketplace coverage would be directly enrolled; those owing a premium would not (but would be informed about how much coverage would cost after the subsidy).

What changes are necessary: Major changes to current law would be necessary to implement this policy. Most importantly, people would need to be entitled to enroll in coverage with financial assistance or Medicaid eligibility based on their prior year income, rather than their current or projected income. In addition, the employer coverage firewall would need to be eliminated, open-enrollment would need to move from November/December to April/May, and IRS information technology would need to be upgraded significantly.

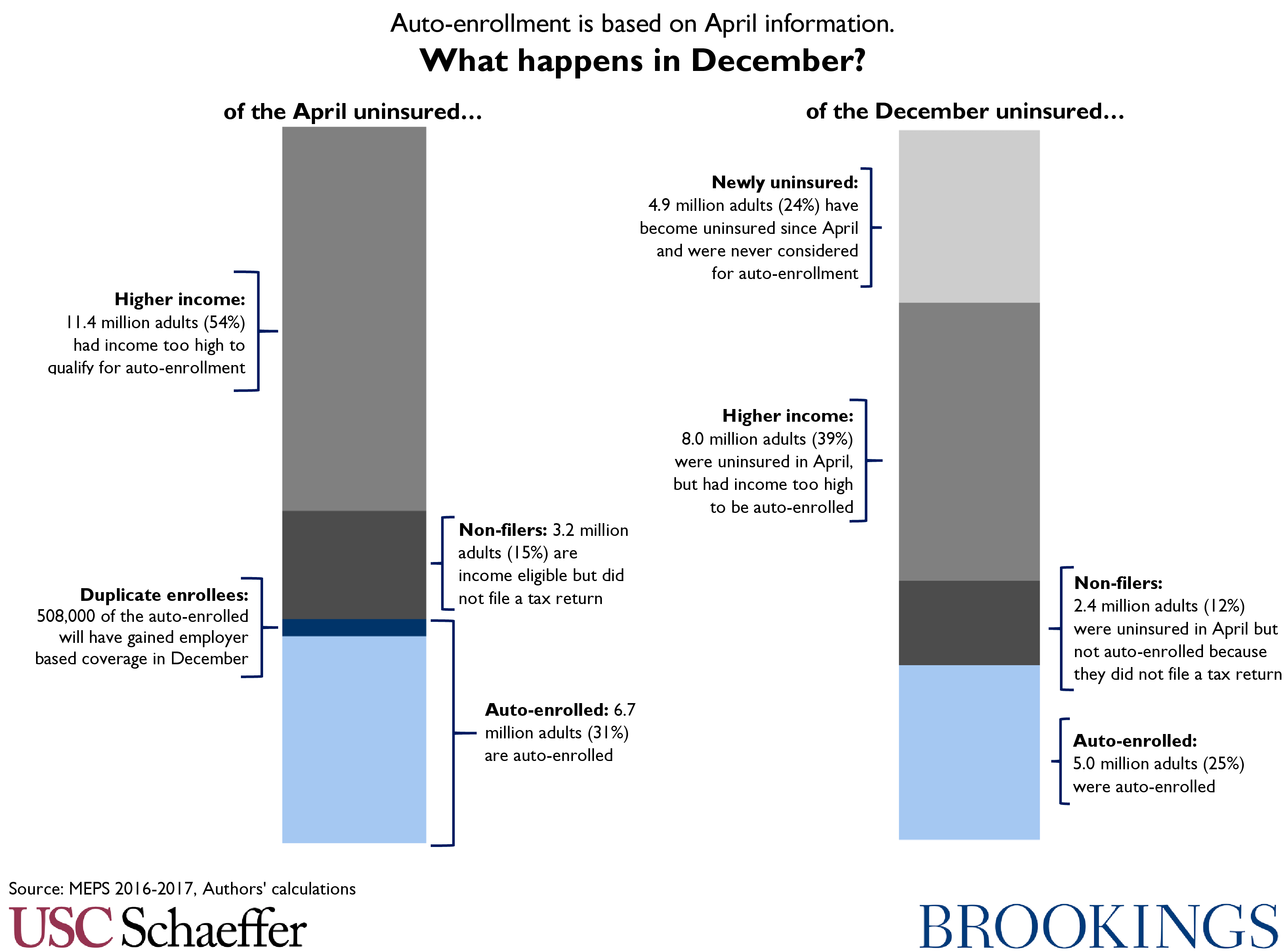

How well it works: We conducted an analysis of 2017 survey data with significant simplifying assumptions, including assuming that all states have expanded Medicaid and simplifying the assessment of who is likely to qualify for a $0 premium Marketplace plan. Under those assumptions, we find that if this system had been operational in 2017, 6.7 million adults would have been auto-enrolled into coverage, the large majority into Medicaid. This would provide insurance for 31 percent of lawfully present adults that would otherwise be uninsured as of April 2017. Of those who were auto-enrolled, 508,000 (7.6 percent) would have gained employer coverage by December 2017. Further, in December, the population that was auto-enrolled would have encompassed 25 percent of December’s otherwise uninsured. Three quarters of December’s uninsured would not have been auto-enrolled for various reasons: 12 percent were uninsured in April and income-eligible but would not have filed a tax return, 39 percent were uninsured in April but had incomes too high to qualify for $0 coverage, and 24 percent had coverage in April and therefore would not have been considered for auto-enrollment.

Taken together, this suggests that forward-looking tax-based auto-enrollment would generate significant coverage gains compared to current law, which could justify the significant operational and policy changes necessary. However, this policy would not achieve universal coverage, and the costs of duplicating employer coverage may be significant.

The full report appears below. For a PDF version of the report, click here.

Introduction

Auto-enrollment into health insurance coverage has earned support across the political spectrum. Analyses of point-in-time coverage and income statistics indicate that 25 percent of the nonelderly uninsured are eligible for Medicaid and another 25 percent are eligible for financial assistance to buy coverage in the Health Insurance Marketplace. Further, many of the Marketplace-eligible uninsured qualify for sufficient financial assistance that they would owe no premium for a bronze plan. Together, the available evidence suggests that at any given time, more than 40 percent of the uninsured qualify for zero premium coverage: 25 percent through Medicaid and another approximately 17 percent through the Marketplace. Therefore, enrolling those eligible – even just those eligible for zero premium coverage – could reduce the uninsured rate substantially.

However, point in time estimates mask the fact that individuals churn in and out of health coverage. A major source of coverage gain and loss is changes in employment status that cause people to gain or lose employer-based coverage, and consumers’ eligibility for and enrollment in public coverage programs also changes over time. Our previous analysis finds that coverage churn can be substantial. Analysis of 2012 survey data found that information about health insurance coverage that is just one month old is already inaccurate for many consumers: 5 percent of those who were uninsured one month ago have gained coverage, while 5 percent of the currently uninsured had coverage last month. Over slightly longer time horizons, information accuracy degrades further: 20 percent of the previously uninsured have gained coverage within 5 months, while 20 percent of the currently uninsured had coverage 5 months ago.

Changes in income can also frustrate attempts to determine who among the uninsured is eligible for coverage in which programs and at what price. Medicaid eligibility is generally based on monthly income and Marketplace financial assistance is based on actual end-of-year income. Therefore, individuals who experience gains or losses in income may see their program eligibility change or may qualify for more or less financial assistance than previously calculated.

Despite these challenges, auto-enrollment remains an attractive policy option. One approach to address the challenges of coverage status and income churn is to pursue retroactive enrollment into coverage: individuals who are otherwise uninsured can be considered “enrolled” in a plan that will pay any health care claims they incur, and eligibility can be assessed and premiums (if any) retroactively collected at a future point. Retroactive enrollment would eliminate the need to know about status changes in real time and would achieve truly universal coverage.

However, policymakers may be concerned that retroactive enrollment may be disruptive or politically infeasible. The creation of a new plan to provide retroactive coverage and requiring after-the-fact premium payments may pose challenges, though we have argued elsewhere that this approach is less disruptive than it may seem. Nonetheless, policymakers may wish to consider other options. An alternative to retroactive enrollment is to pursue a forward-looking tax-based approach, where uninsured consumers eligible for $0 premium coverage options would be enrolled after filing their taxes each year.[1] Unlike retroactive enrollment, this will fall short of achieving universal coverage – because not all uninsured have a $0 premium options, because not everyone files taxes, and because coverage churn will generate new uninsured over the course of the year. But it is an incremental approach that could still lead to significant coverage gains.

The remainder of this paper attempts to understand how successful an optimally executed tax-based auto-enrollment approach could be. It describes the type of policy under consideration, then considers some of the high-level policy and operational changes that would be needed to enable such an approach. Finally, it uses two survey data sources to attempt to simulate how successful such a policy would have been in enrolling the eligible uninsured if it had been operational in past years.

A Tax-Based Auto-Enrollment Approach

The policy considered here would operate as follows. On the individual tax return, tax filers would indicate whether each member of their household had coverage as of the date of filing (e.g., April 15, 2020) and if they consented to being enrolled in coverage if they were uninsured. The prior year income (e.g. calendar year 2019 income for the household, as reported on the tax return), would be used to determine if uninsured household members were eligible for Medicaid or for Marketplace coverage.

- Uninsured consumers with prior year income making them eligible for their state’s Medicaid program would be enrolled by the Medicaid agency, with coverage running from June through May (e.g., June 1, 2020 through May 31, 2021).

- Uninsured consumers with prior year income making them eligible for Marketplace coverage with $0 premium would be enrolled by the Marketplace into a $0 premium plan at the highest actuarial value with a $0 option, with coverage running from June through May (e.g., June 1, 2020 through May 31, 2021). For some consumers this might be a silver plan, but many would only qualify for $0 premium bronze plans.[2]

- Uninsured consumers with prior-year income too high to qualify for $0 premium coverage would receive outreach from the Marketplace estimating their premiums for the coming year and encouraging them to enroll.

Before enrolling a consumer, the Marketplace or Medicaid agency would verify citizenship or immigration status using the Social Security Number provided on the return. Consumers who could not be verified and those filing with other types of Taxpayer Identification Numbers would not be enrolled, but could receive outreach. There would be no need for additional income verification because prior year income, as reflected on the tax return and used as the basis for the eligibility assessment, would now be sufficient for eligibility purposes. Coverage renewals at the end of the benefit year (e.g. in May of 2021) would operate according to normal Medicaid or Marketplace renewal rules.

Policy and Operational Changes Necessary

Many significant policy and operational changes would be necessary to implement this approach. These include:

- Medicaid and Marketplace financial assistance must be converted to 12-month continuous eligibility based on prior calendar year income. Under current law, a household’s 2019 calendar year income might suggest that they are eligible for Medicaid or for Marketplace financial assistance sufficient to enroll in a $0 premium plan in 2020 – but it does not actually establish that eligibility. In order to allow auto-enrollment to operate, eligibility rules must be modified so that prior calendar year income establishes an entitlement to coverage in Medicaid or to a specific amount of Marketplace financial assistance. Consumers who experience significant reductions in income would be permitted to opt into a voluntary process to claim additional assistance, potentially including a “reconciliation” process for Marketplace financial assistance and Medicaid’s monthly income methodology as under current law, but those with income increases would not lose eligibility. This change would be expected to increase the number of people eligible for free coverage over the course of the year.

- The employer coverage firewall must be eliminated. Under current law, consumers are not eligible for Marketplace financial assistance if a member of their household has an affordable coverage offer from an employer. Nine percent of the uninsured are barred from financial assistance by this rule today. Yet, under the tax-based auto-enrollment approach described here, one cannot identify these individuals at tax filing without asking a lengthy series of additional questions – and one cannot identify individuals who gain a qualifying coverage offer during the benefit year at all. To enable the type of auto-enrollment described here for $0 premium Marketplace enrollees, the employer coverage firewall must not remain in effect; individuals would be eligible for assistance regardless of their employer’s coverage offer.

- One possible alternative to the current law firewall would be to disenroll consumers who gained enrollment in (not just eligibility for) employer coverage, which would require additional reporting by employers. For example, employer reporting to the National Database of New Hires could be modified to include identifying information for individuals enrolled in the employer’s coverage. Periodic checks of this database could be used to identify those who should be disenrolled from Marketplace coverage (after notice and opportunity to opt out of disenrollment). This would, however, be a significant operational undertaking. Further, it would not address the fact that many individuals will chose to forego enrollment in employer coverage if Marketplace coverage is more affordable, but it could limit the extent to which truly duplicate enrollment accretes over time.

- Marketplace open enrollment should run in April and May, with coverage beginning June 1. Beginning the coverage benefit year as close as possible to the standard tax filing deadline will allow enrollment to be based on the most accurate information possible. This shift becomes possible only if Marketplace financial assistance is no longer “reconciled” based on calendar year income, but, as noted above, such a change is also necessary for auto-enrollment to function.

- Major improvements in IRS information processing are necessary. To operate this type of system, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) must process tax return information and make it available for coverage enrollment purposes very quickly. Indeed, the timeline specified above requires information to be used for enrollment purposes 6 weeks after filing. This maximizes the accuracy of the information used. However, the IRS does not currently have the capability to execute a process at this speed. For example, today, information about prior year income is not made available to health care agencies for verification purposes through the Data Services Hub until late summer, though some summary statistics on tax filing are available as early as May. Major investment in IRS information technology would be necessary to enable the agency to operate at the speed described here.

These are fairly large changes. In addition, they would come with a significant federal fiscal cost—and some costs for the states as well—even before considering the cost associated with increased enrollment in subsidized coverage due to the auto-enrollment policy itself. At the same time, these changes would also be expected to increase enrollment and lower premiums, apart from their role in enabling auto-enrollment, by simplifying the enrollment and outreach landscape. Assuming these challenges can be overcome, we turn now to an attempt to simulate how effective this policy could be in reducing the uninsured.

Simulating the Effectiveness of Tax-Based Auto-Enrollment

As noted above, a significant fraction of the uninsured at any given point in time qualify for coverage without any premium and could potentially benefit from tax-based auto-enrollment. But churn in coverage and income can frustrate this approach. We use two sources of survey data to estimate how effective a tax-based auto-enrollment policy would have been in targeting the uninsured if it had operated in a prior year. Recall that a tax-based auto-enrollment policy determine eligibility based on uninsured status from April (as reported on tax returns) and income for the prior calendar year. The household’s prior calendar year income would be sufficient to establish an entitlement to Medicaid or Marketplace financial assistance for the 12-month period beginning in June of the following year. Therefore, we identify consumers’ insurance status in April and their income in the prior calendar year, and track changes over time.

We are concerned with two metrics assessing the impact of coverage churn on the accuracy and effectiveness of potential auto-enrollment: the duplicate enrollment rate and the uncaptured uninsured rate. The duplicate enrollment rate for a specific month measures the fraction of the April uninsured that have gained employer coverage for a month during the June to May benefit year.[3 ] The uncaptured uninsured rate for a month during the benefit year measures the fraction of the current month uninsured that had coverage in April (and therefore could not have been captured by auto-enrollment). We are also interested in the share of the April uninsured who have incomes too high to qualify for auto-enrollment into $0 premium coverage, or who are income-eligible but will not have filed a tax return.

Data Sources and Approach

The Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component (MEPS-HC) tracks coverage status in each of the 24 consecutive months spanning two calendar years and includes a measure of yearly income in each calendar year of the study. MEPS data is available for multiple two-year periods, including the 2011-2012 and 2016-2017 panels that are analyzed here. In addition, the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) has historically tracked coverage status and income in each month over a multi-year period, including the 2008 panel that spanned 2008-2013. SIPP data spanning 2011 through 2013 were used in this analysis.

We assume that all states have expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act and provide coverage – with no premium – to anyone below 138 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). Compared to current policy, this assumption will increase the proportion of people eligible for auto-enrollment into Medicaid and decrease the proportion eligible for auto-enrollment into a $0 premium Marketplace plan, likely by fairly substantial margins. Our analysis is limited to non-elderly adults, ages 19-64. We treat all adults as potentially eligible and do not attempt to model coverage eligibility based on citizenship or immigration status, and scale our results to reflect the lawfully present population. A detailed discussion of methods and results appears in the Appendix.

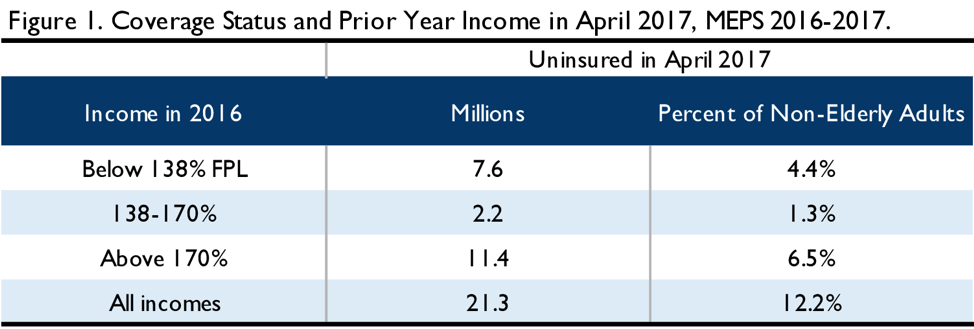

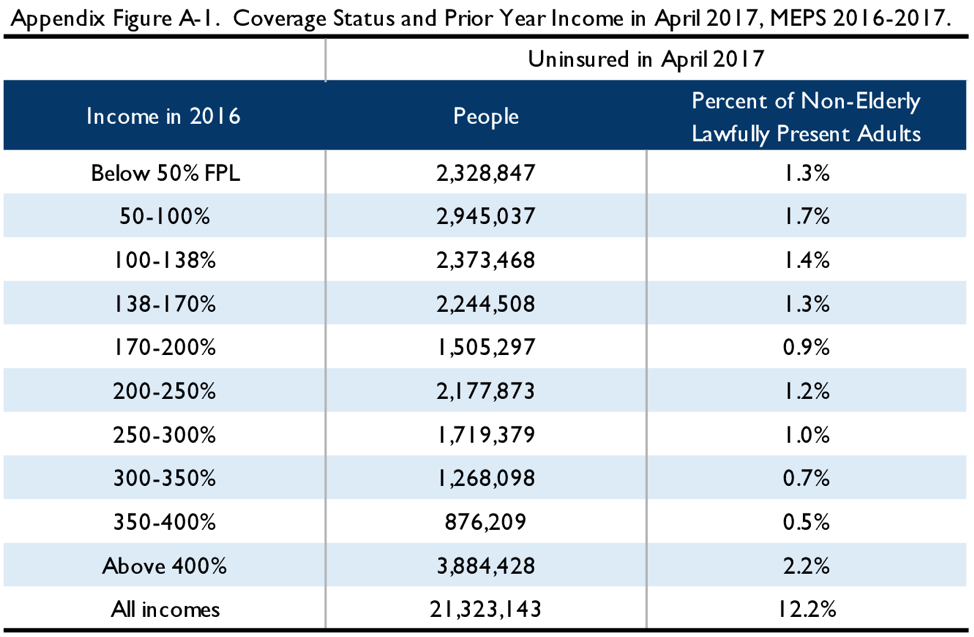

Simulating Auto-Enrollment in 2017

Analysis of MEPS data from 2016-2017 allows us to simulate the impact auto-enrollment would have had if it had been operational in 2017. We consider coverage status as reported to MEPS in April of 2017 and income as reported for calendar year 2016. We find 21.3 million lawfully present, non-elderly adults were uninsured in April 2017. As depicted in Figure 1, we can divide the April uninsured into those that have a 2016 income below 138 percent FPL and could be enrolled in Medicaid (7.6 million people) assuming all states have expanded, those that have a 2016 income between 138 percent FPL and 170 percent FPL and are reasonably likely to be eligible for a $0 premium Marketplace plan (2.2 million people), and those with a 2016 income above 170 percent FPL who are less likely to be eligible for a $0 premium plan (11.4 million people).[4]

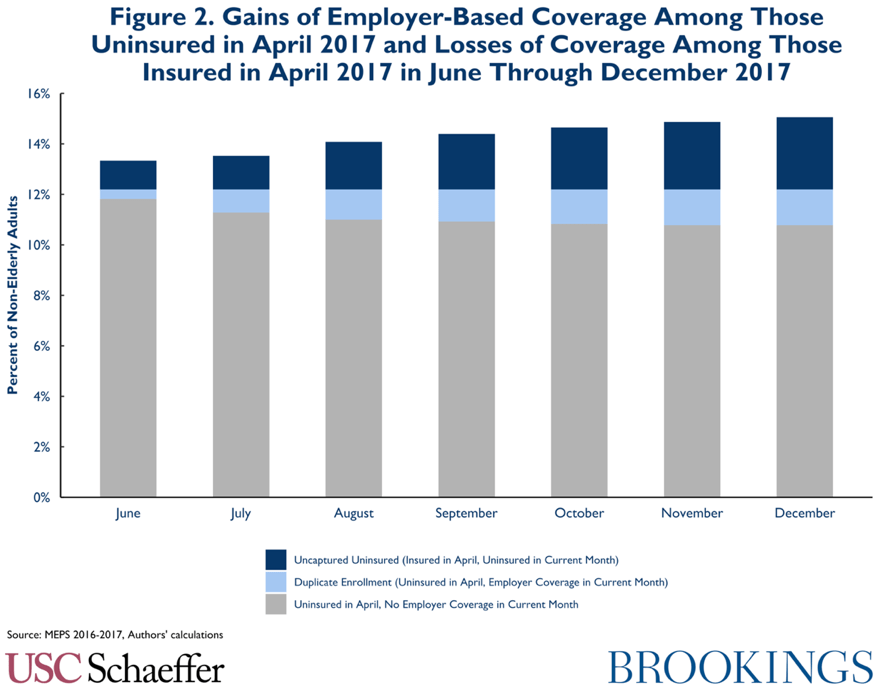

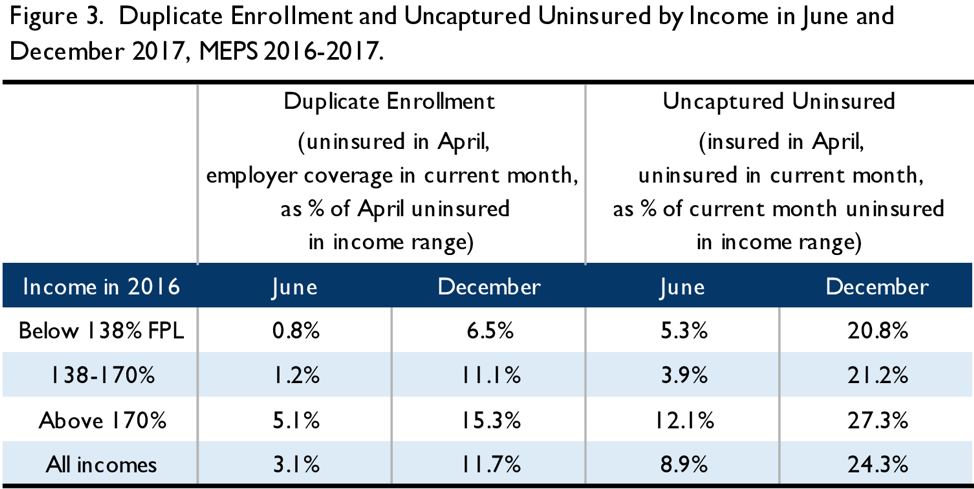

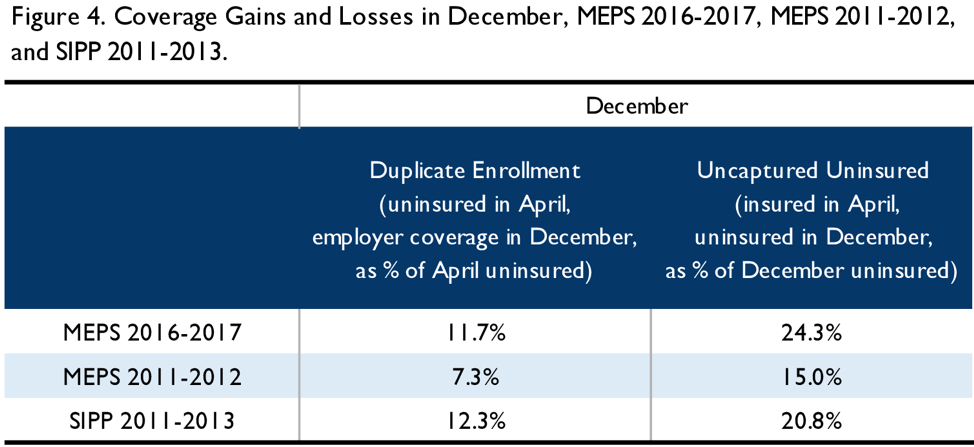

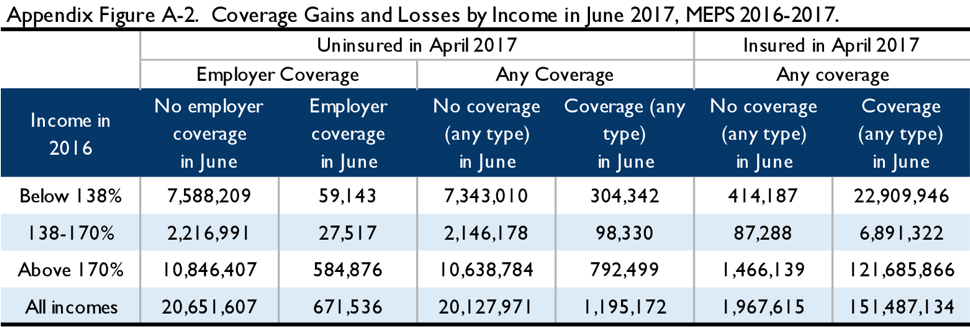

Of course, over time this coverage information will become less accurate. To determine the duplicate enrollment rate, we examine gains of employer-based coverage[5] among the April uninsured. As shown below, by June 2017, when auto-enrollment based on the April coverage information would have occurred, 3.1 percent of the 21.3 million people (of all incomes) who were uninsured in April have gained employer-based coverage; by December 11.7 percent have done so. To the extent members of this group were auto-enrolled, their auto-enrollment in Medicaid or Marketplace coverage would duplicate employer coverage.

To determine the uncaptured uninsured rate, we examine losses of coverage (of any type) among the population that was insured in April at all income levels, as a fraction of the total uninsured population for that month. In June, 8.9 percent of the uninsured could not even have been considered for auto-enrollment because they have become uninsured since April, and by December this rises to 24 percent.

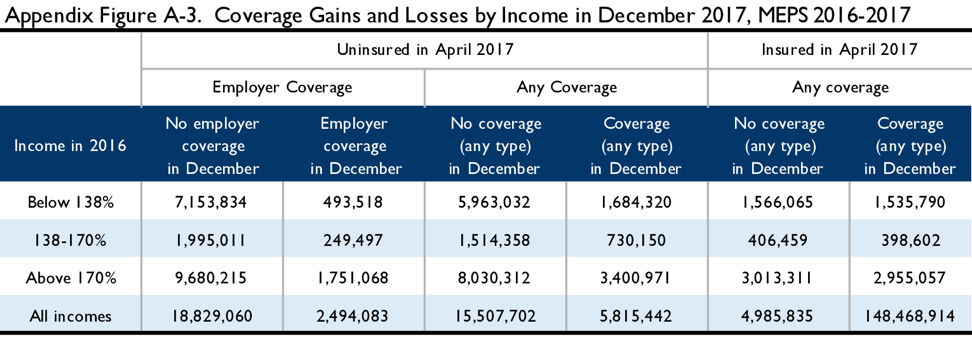

It is useful to consider the impact of this coverage churn by income. Figure 3 illustrates these differences. Notably, potential duplicate enrollment due to employer-based coverage is largely concentrated among the higher income population that is least likely to be eligible for Medicaid or a $0 premium bronze plan, and therefore less likely to have been auto-enrolled in the first place. The uncaptured uninsured due to coverage losses are more evenly distributed across the income spectrum, though they also are concentrated to some degree among those with higher incomes.

Finally, we estimate the share of the April uninured that are income-eligible for auto-enrollment but cannot be auto-enrolled because the household does not file a tax return. Based on estimates from the Tax Policy Center,[6] we conclude that 34 percent of the uninsured with incomes below 138 percent FPL and 27 percent of the uninsured with incomes between 138-170 percent FPL will not have filed taxes. We adjust the proportion of the April income-eligible uninsured that can be auto-enrolled accordingly.

Taken together, this analysis indicates that of those uninsured in April 2017, about 6.7 million adults (31 percent of the April uninsured) could likely have been auto-enrolled, including 5 million adults into Medicaid and 1.7 million adults into $0 premium Marketplace coverage. Of the 6.7 million adults likely to be auto-enrolled, in December, the duplicate enrollment rate due to a gain of employer coverage would be 7.6 percent (508,000 adults). Among the April uninsured, 14.6 million adults (69 percent) will not be auto-enrolled: 11.4 million with incomes too high and 3.2 million who are income eligible but did not file a tax return.

On the other hand, the December uncaptured uninsured rate is 24 percent (5 million adults): 24 percent of the December uninsured have become uninsured since April and therefore could not be reached by autoenrollment. An additional 39 percent (8 million adults) of the December uninsured were also uninsured in April but had prior year incomes likely too high to qualify for a $0 premium plan, and 12 percent (2.4 million adults) were income eligible but did not file a tax return. Therefore, 25 percent of December’s otherwise uninsured would likely have been reached by auto-enrollment the prior spring because they were uninsured at the time, filed a tax return, and had 2016 income below 170 percent FPL.

Put another way, 31 percent of the April uninsured can likely be reached by auto-enrollment, and that population will encompass 25 percent of the December uninsured.

Simulating Auto-Enrollment in 2012

MEPS provides a picture of post ACA coverage churn, but it has important limitations for simulating the auto-enrollment policy described here. First, it does not extend for the full coverage period, with the survey terminating in December while coverage would extend until May. Second, it provides only a calendar year snapshot of income. Therefore, to the extent consumers experience income decreases that would make them newly eligible for Medicaid or for $0 premium plans, MEPS does not allow examination of those changes. Using SIPP data can address both of these limitations; however, the most recent SIPP data suitable for this analysis covers 2011-2013.

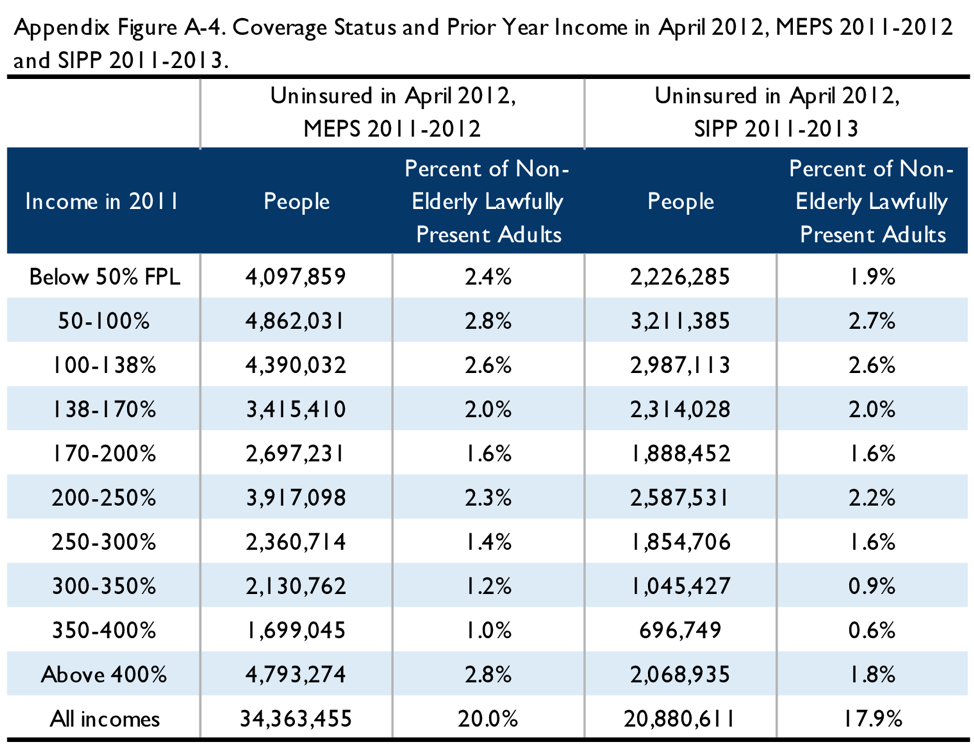

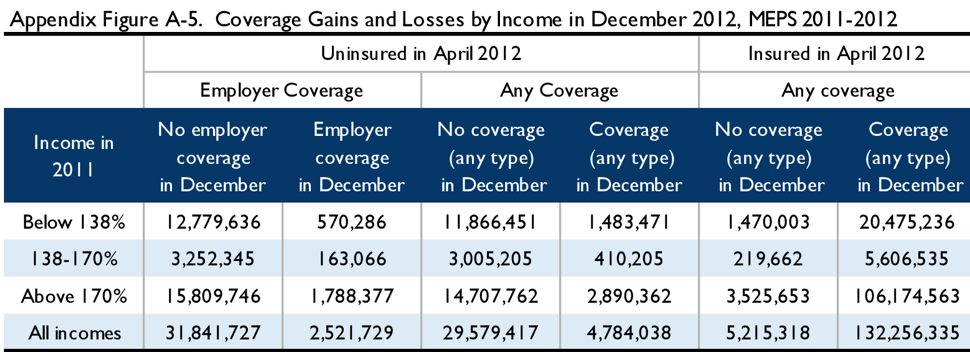

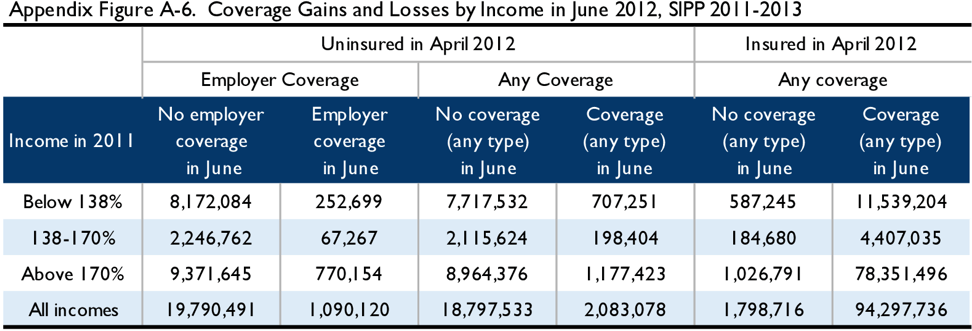

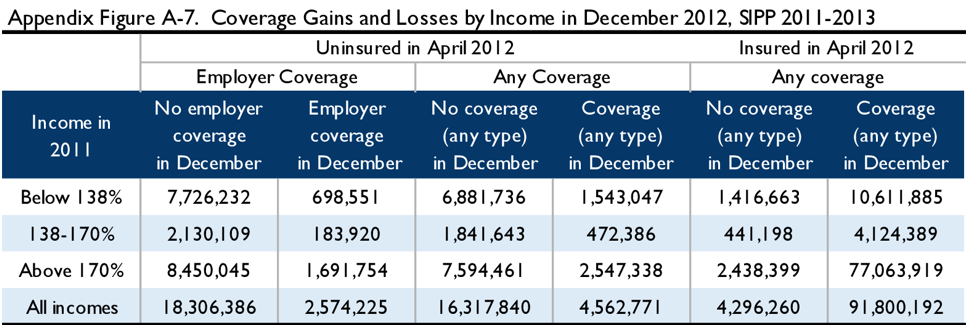

Therefore, we replicated the simulation described above using SIPP data for 2011-2013, looking at uninsured status in April 2012, calendar year 2011 income, and coverage and income in June 2012 through May 2013. We also analyzed MEPS data from the 2011-2012 panel, to examine if survey differences had an important impact. The total number of uninsured was – as expected – much larger in the 2012 MEPS simulation than in the 2017 MEPS simulation, and the SIPP simulation showed a smaller number of uninsured in 2012 than MEPS over the same time period. (See Appendix Figure A-4.) The patterns of coverage gains and losses showed some similarities across all three simulations, as shown in Figure 4.[7]

Comparison of the 2017 MEPS simulation and the 2012 MEPS simulation suggest that post-ACA churn is larger – as a percentage of the uninsured – than pre-ACA churn, though care should be used in interpreting this result as each simulation covers only a single 8-month time span. Nonetheless, the observation is consistent with the claim that the ACA has reached a larger share of the chronically uninsured than of the short-term uninsured. Further, SIPP shows a higher degree of churn than MEPS over the same time period. This suggests caution in generalizing too far from any single simulation.

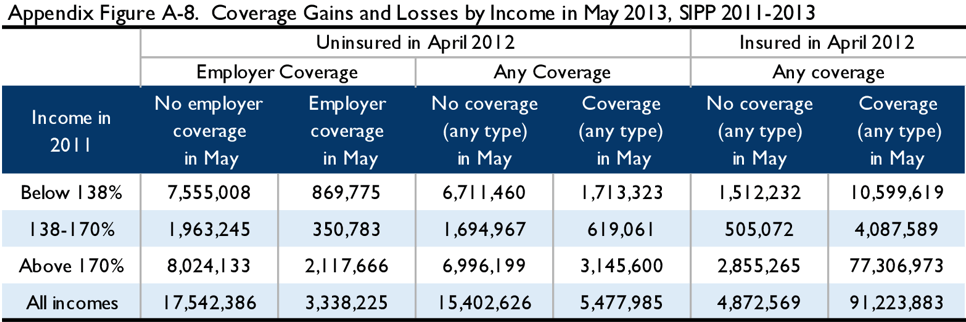

Nonetheless, extending the SIPP simulation through May shows some additional erosion in coverage accuracy. In the 2012 SIPP simulation, the duplicate enrollment rate (across all incomes) rose from 5 percent in June to 12 percent in December to 16 percent in May, while the uncapturable share of the uninsured rose from 9 percent in June to 21 percent in December to 24 percent in May. Because implementation of the ACA changed the income-composition of the uninsured (see, e.g., Appendix Figures A-1 and A-4), caution should be used in generalizing from a pre-ACA simulation of the income of the uninsured. With that in mind, the 2012 SIPP simulation shows that 51 percent of the April 2012 uninsured had incomes below 170 percent FPL. Using the same estimates as above regarding the share of income-eligible households who fail to file a tax return, we find that 41 percent of the April uninsured are likely to be reached by auto-enrollment, and this group would constitute 32 percent of the December uninsured and 31 percent of the May uninsured. (See Appendix Figures A-7 and A-8.)

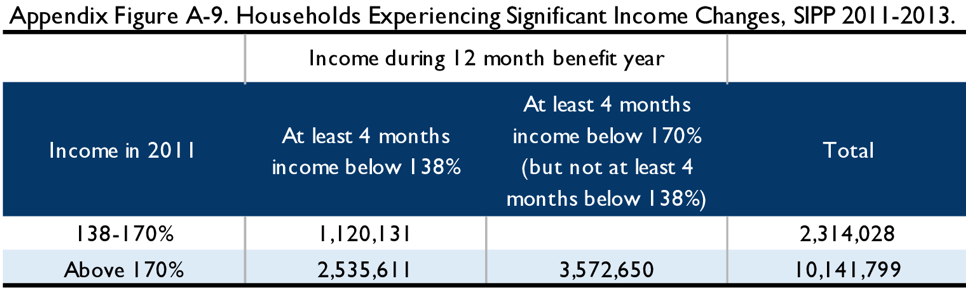

Bearing in mind the same caveats, it is also useful to consider how decreases in income would affect the accuracy of the auto-enrollment process. (Under the policy described above, increases in income would not affect eligibility.) In particular, of the April uninsured with incomes between 138 percent and 170 percent FPL in the prior year, a significant fraction become eligible for Medicaid over the course of the Marketplace benefit year. Specifically, 48 percent experience at least 4 months with income below 138 percent FPL during the 12-month benefit year. This group is likely to have been enrolled in a $0 premium plan with high cost-sharing relative to the Medicaid coverage for which they have newly become eligible. Similarly, of the April uninsured who had base year incomes above 170 percent FPL (who are therefore unlikely to be determined to have access to a $0 premium plan), 35 percent experience at least 4 months with incomes below 170 percent FPL, including 25 percent who experience at least 4 months with incomes below 138 percent FPL.

Limits of this Analysis

It is important to note that these simulations fail to capture several dynamics that would be relevant to the execution of an auto-enrollment strategy. Perhaps most importantly, the assumption that those with incomes below 170 percent FPL are likely eligible for $0 premium plans and those above are likely not is a very strong simplifying assumption. In reality, the distribution of $0 premium options varies based on age, geography, and other factors, with those who face the highest benchmark premiums the most likely to be eligible for $0 premium coverage – so some people above 170 percent FPL will be eligible, and some below will not. However, it is beyond the scope of this analysis to model actual $0 premium eligibility. Further, as noted above, these figures assume that all states have expanded Medicaid, which depresses the share of the uninsured eligible for $0 premium private coverage, but increases the total number of people eligible for some coverage option.

In addition, these simulations assume everyone in the target universe who will file a return will do so by April 15, when in fact some file late. This leads us to overstate the number of people considered for auto-enrollment. In addition, we use April coverage status as a proxy for what would be presented on the tax return, when in fact many people file taxes in February or March, leading to somewhat less accuracy than we find here. We do account for non-filers, but assume a household’s failure to file is uncorrelated with insurance status, which may not be an accurate assumption. We also ignore the impact of changes in household composition for births, marriages, divorces, etc. The simulations do not consider potential challenges in verifying citizenship or immigration status among those eligible or other operational obstacles.

Taken together, these factors suggest that we will overstate the reach of auto-enrollment. However, we believe the analysis provides a useful picture of the potential scope of population-level auto-enrollment approaches.

Conclusion

A forward looking, tax-based auto-enrollment system would collect coverage information on a tax return in April and use it to enroll eligible consumers into $0 premium plans for a benefit year that runs from June through May. Implementing this type of enrollment system would require significant policy and operational changes.

Based on a simulation using coverage and income data from 2016-2017, we find that 31 percent of the April uninsured file taxes and have incomes below 170 percent FPL, such that they are likely to be eligible for $0 premium coverage into which they can plausibly be auto-enrolled. By December, the group of consumers who could have been auto-enrolled represents 24 percent of the December uninsured, while 7.6 percent of those likely to have been auto-enrolled have gained employer coverage that might duplicate their auto-enrollment. Analysis of survey data from 2011-2013 suggest that these problems would continue as coverage extended into May, and that a significant fraction – perhaps as high as 1 in 2 – of those auto-enrolled into private insurance coverage could in fact become eligible for Medicaid at some point during the benefit year.

Thus, a forward looking, tax-based approach to auto-enrollment would plausibly generate significant coverage gains compared to current law, and those gains could justify the operational and policy changes necessary to make such a system possible. However, it should not be thought of as a policy that can achieve universal coverage, and the costs of duplicating employer coverage may be significant. In that respect, other approaches to enrollment, such as retroactive auto-enrollment policies, would fare better, though of course come with their own limitations.

Appendix

We use two primary survey data sources for our analysis. The Census Bureau’s Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) is a national longitudinal household survey that collects information on topics such as income, program participation, employment, and health insurance coverage. In addition, the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) Household Component (HC) provides information on topics such as health insurance, health status, and socio-economic characteristics.

For SIPP, we focused on adults ages 19 to 64 in December 2011 who reported valid insurance status information for all 29 months through May 2013. We weighted the observations by the individuals’ survey weight in April 2012 when taxes are filed. Individuals were considered insured if they reported coverage in Medicare, Medicaid, military health care, or private health insurance. Individuals were considered to have employer coverage if they reported coverage in military health care or identified the source of coverage as current employer, former employer, or union.

For MEPS-HC, we focused on adults ages 19 to 64 in December 2011 (Panel 16) and December 2016 (Panel 21) who reported valid insurance status information for all 24 months. We weighted the observations by the longitudinal weight to provide national estimates. Individuals were considered insured if they reported coverage in Medicare, Medicaid, SCHIP, TRICARE or other public or private insurance. Individuals were considered to have employer coverage if they reported coverage in TRICARE/CHAMPVA or identified the source of coverage as employer or union.

Income level relative to FPL was constructed using the family income and size provided in each dataset. Annual income was calculated by summing monthly family income for all 12 months of the calendar year in SIPP and using the annual total family income in MEPS. It is important to note that the family size and income used may not correspond to the tax unit size and Modified Adjusted Gross Income (MAGI) used to determine Medicaid and Marketplace eligibilities.

Estimates provided by researchers at the Tax Policy Center indicate that 34.2 percent of tax units with income under 138 percent FPL, 26.8 percent of tax units with income 138-170 percent FPL, and 5.0 percent of tax units with income above 170 percent FPL do not file for taxes; we adjusted our estimates to account for those who cannot be auto-enrolled because they fail to file a tax return.

This analysis assumes that all observations in the MEPS and SIPP data represent citizens or lawfully present immigrants. Accordingly, we scale our results to exclude the undocumented population. We scale down our count of the uninsured by 16.2 percent, based on estimates from the Urban Institute.[8] We also scaled down total non-elderly adults by 4.4 percent based on Pew’s 2017 estimate of 10.5 million undocumented immigrants, DHS’s estimate that non-elderly adults account for 84 percent of the undocumented, and the Census 2017 population estimate of 201 million non-elderly adults.

To identify households who experienced at least 4 months of income below a relevant threshold we considered the SIPP monthly income variable for each month in the benefit year (June 2012 to May 2013) as compared to the income for 2011. Months below a threshold did not have to be consecutive.

Results of MEPS 2016-2017 Simulation

The tables below illustrate the results of the simulation in the 2016-2017 MEPS. Appendix Figure A-1 illustrates the 2016 income of the April 2017 uninsured. Appendix Figure A-2 examines coverage status in April and June of 2017 by income: those below 138 percent in 2016, those between 138 percent and 170 percent FPL in 2016, and those above 170 percent FPL. Appendix Figure A-3 examines coverage status in April and December of 2017 across the same income groups. These figures are not adjusted to reflect non-filers, but are scaled to reflect lawfully present adults.

Results of the 2012 Simulations

The tables below illustrate the results of simulations from the 2011-2012 MEPS and 2011-2013 SIPP. Appendix Figure A-4 depicts the 2011 income of the April 2012 uninsured in both surveys. Appendix Figures A-5 through A-8 examine coverage status in April 2012 and either June 2012, December 2012, or May 2013, by income, in MEPS and in SIPP. Finally, Appendix Figure A-9 examines the income during the 12-month benefit period as compared to income in 2011 in SIPP. As above, these figures are not adjusted for filing status, but are scaled to the lawfully present population.

Limitations

The discussion in the main text describes a number of features of an auto-enrollment policy that are not captured by this methodology, including the actual distribution of $0 premium bronze eligibility, a more accurate exclusion of potential enrollees based on citizenship and immigration status, changes in household composition, and states failure to expand Medicaid. In addition, there are several limitations to the data sources and methods used in this analysis. One notable limitation of the SIPP is the seam bias, which is the tendency to report the same status for the reference months during one interview and to report changes in status in between the months of the current and subsequent interview. SIPP participants are interviewed every four months so the duration of health insurance coverage spells may be in multiples of fours. By comparison, the influence of the seam bias is less prominent in MEPS likely due to their different interviewing and sampling methods.

Attrition, a phenomenon where survey participants drop out or fail to respond, is also a common problem in a longitudinal survey. We expect a higher sample loss rate for the SIPP data we examined (Wave 8 to 16) than for the data collected in earlier waves. While the Census Bureau tries to correct for the bias using weighting and imputation, our estimates may still be distorted.

Although MEPS may be better than SIPP in dealing with the seam bias, one limitation of MEPS is that the longitudinal household data only spans over two years. Therefore, the simulations using MEPS will not show the income and coverage status changes for the full benefit year of the auto-enrollment. In addition, the MEPS instrument design changed beginning Spring of 2018, affecting the last round (round 5) of the MEPS 2016-2017 data file. While the affected data was transformed to conform to previous study designs, the precise level of impact is unknown.

The authors thank Kathleen Hannick of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy and Gordon Mermin of the Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center for assistance in this research.

You must be logged in to post a comment.