Many of us have studied our hands and noticed whether our index or ring finger is longer. For most, this is a purely aesthetic concern, or the vague memory of something we heard somewhere about what this difference means. It turns out, whether you have a longer index or ring finger means a lot.

Research suggests that having a longer ring finger compared to index finger reflects greater exposure to male hormones during an individual’s time in their mother’s womb. There are differences between and within sexes in finger lengths associated with relatively more masculine versus feminine development. In fact, prenatal hormone exposure may provide important insights into the sources of sex differences in a variety of health conditions in adults.

Of course, we cannot measure prenatal hormone exposure in people. But we can use relative length of the second and fourth digits (that is, the index and ring fingers) as an indirect indication.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

Two studies presented at the Alzheimer’s Association International Conference last week present new data about the link between relative digit length and whether individuals develop cognitive impairment or dementia when they are older.

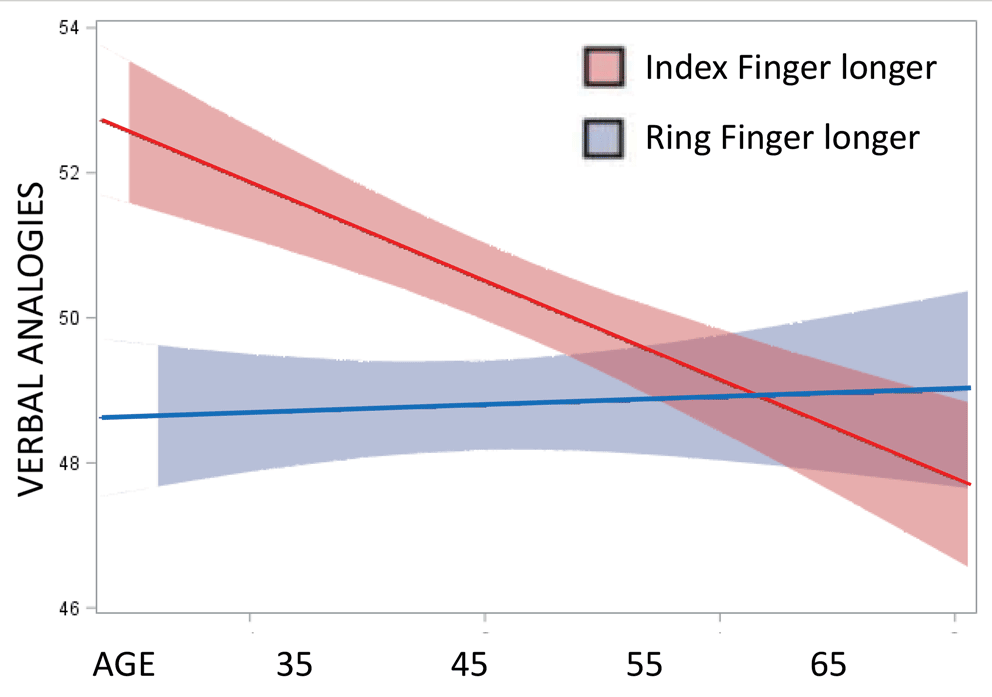

Gatz and her colleagues used USC’s Understanding America Study, a probability-based online panel of more than 8,000 American households, to compare those who reported relatively longer index finger to those who reported relatively longer ring finger. Panel participants previously completed three web-based cognitive tests—number series, picture vocabulary, and verbal analogies.

The team reported a statistically significant pattern for women, especially on number series and verbal analogies. At younger ages, women with relatively longer index fingers scored higher than women with relatively longer ring fingers, consistent with verbal abilities being better in girls than boys. Also in women with relatively longer index fingers, those who were older scored lower than those who were younger, consistent with age-related changes in cognition. However, at the oldest ages, women with relatively longer ring fingers scored the same or higher than women with relatively longer index fingers, and older women scored just as well as younger women. There were no statistically significant differences for men.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

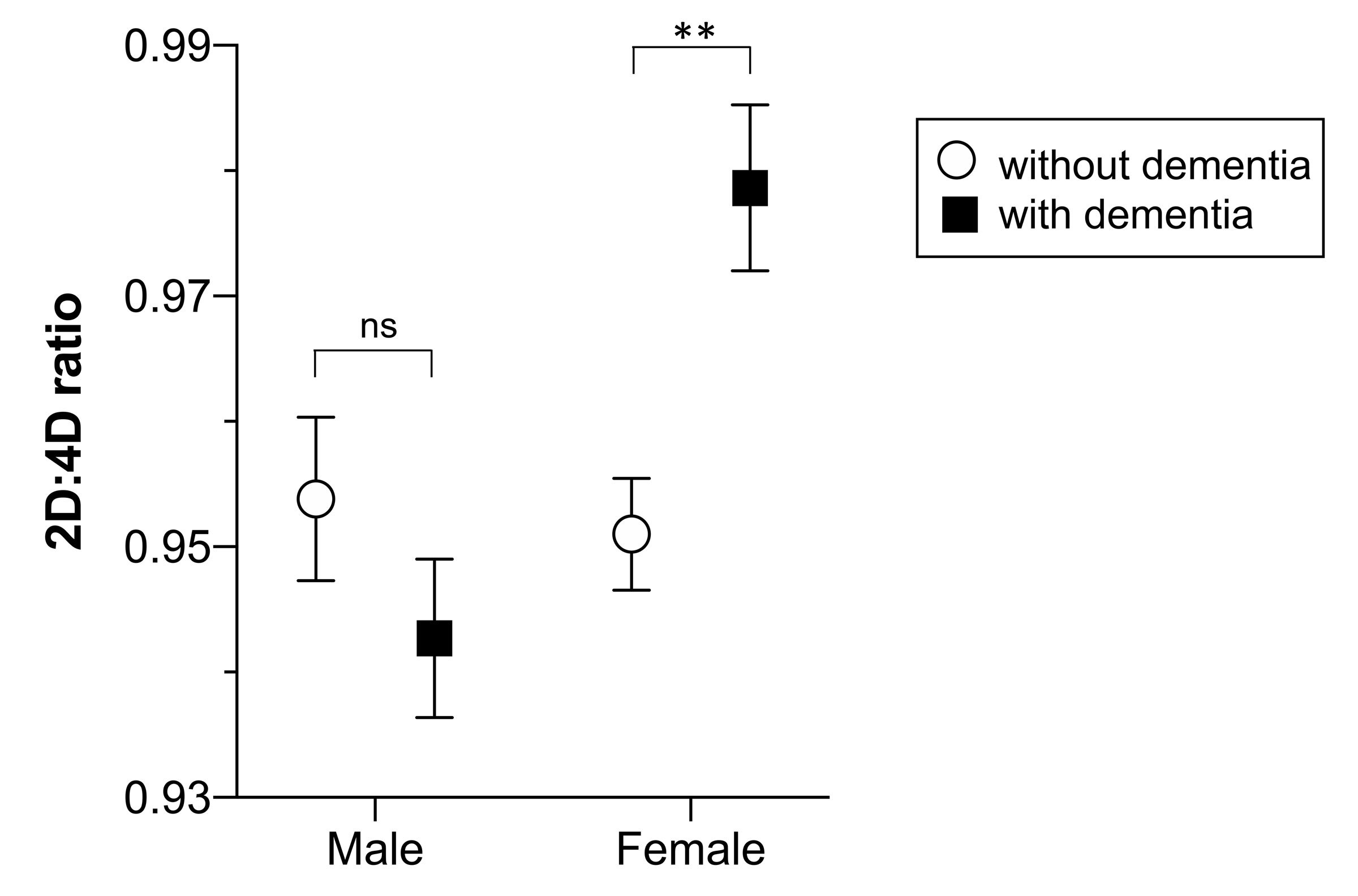

Pike and his colleagues recruited older adults from community adult care centers and assisted living facilities. Those with a positive history of dementia or significant memory impairment comprised the ‘dementia’ group; all other subjects were classified as ‘non-dementia’. Research assistants used a scanner to make an image of the participants’ hands. Then they measured lengths of second (2D) and fourth digits (4D) using a caliper. These values were used to calculate a ratio of 2D:4D. All measurements were made by an investigator who was blind to who was designated as dementia status.

Women with dementia had a significantly more feminine (higher) 2D:4D compared to women without dementia, suggesting a female pattern of early development may predispose to dementia. The difference was not statistically significant for men.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

The results of these two studies suggest that prenatal male hormone exposure may help to preserve cognition in older women, potentially making them less vulnerable to Alzheimer’s disease. These findings contribute to understanding possible bases of sex differences in dementia risk. Currently the best recommendations for maintaining healthy cognition at older ages include a healthy lifestyle such as regular physical activity and good cardiovascular health.

You must be logged in to post a comment.