Emerging economies are in the midst of a mobile revolution: phones and associated add-on services have been found to improve the functioning of rural markets, boost educational outcomes, and even reduce poverty. However, the ability to access and own a phone, and thus reap its benefits, is not equally available to men and women, particularly for women in South Asian countries. India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh continue to have exceptionally high gaps in cell phone ownership, even compared to countries with similar costs of cell service (International Telecommunication Union (ITU), 2014) and income (World Bank, Gross National Income (GNI) per capita averaged across 2014, 2015, and 2016). According to data from Intermedia’s 2015 and 2016 Financial Inclusion Insights Surveys, India’s gap in ownership is 33 percentage points, and nearly half of women who report having access to a phone must borrow one to use one, as compared to only 16 percent of men. This gap is worrisome, as it runs the risk of exacerbating other gender inequalities in a country where women already lag behind men.

Currently there is little research on what is driving India’s mobile gender gap, what can be done to address it, and what closing the gap would mean for women’s welfare. Our team of researchers from USC CESR, Princeton, Duke, and Evidence for Policy Design at Harvard Kennedy School is undertaking a study to answer these questions. Below we summarize some initial findings, and discuss how they add to our understanding of India’s digital gender divide.

Gaps Persist Across Demographics

One natural leading hypothesis is that the mobile gender gap is just a byproduct of India’s existing gender gaps in human capital and income. Although the gender gap certainly declines with factors like education and literacy, this is only part of the story. In fact, we found that phone ownership and access gaps are persistent across many of the standard demographics associated with higher women’s social status, such as higher educational attainment, and living in urban areas. For example, when segmenting by demographics, the group with the lowest gender gap was urban residents with post-secondary education. Yet even here, the gap was a still-substantial 10 percentage points. This suggests the other factors, such as cultural or social norms, could play an important role in shaping women’s use and ownership of phones.

Gender Norms are Central

To make progress on norms, we first reviewed literature to identify broad-based gender norms found in many parts of India. The resulting framework, coupled with detailed analysis of our qualitative data, uncovered several clear ways existing norms have started to shape mobile phone use: First, women are expected to remain chaste before marriage to ensure they can attract a suitable husband, something a majority of our interviewees believed would be jeopardized by a woman being seen using a mobile phone. Second, after marriage many women are expected to assume the exclusive role of caretaker to their children and husband. Many male and female interviewees felt that given this reality there is no reason a woman would need a cell phone, since phones were seen as most useful for market-based work and entertainment.

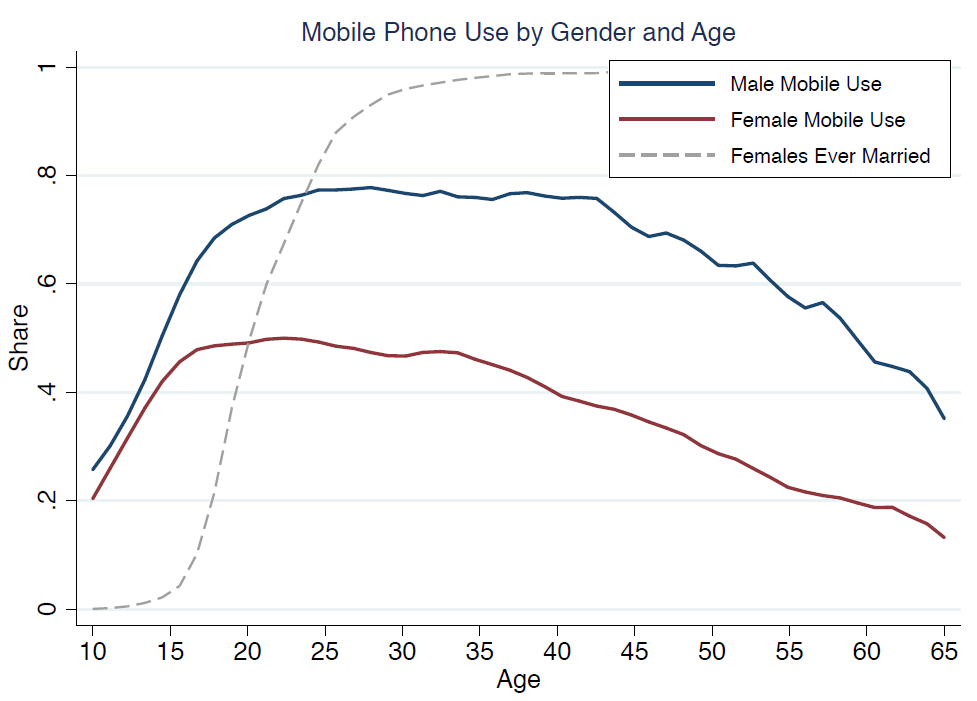

An exploration of the change in phone use over the course of women’s lives provided further evidence that marriage norms play a key role in shaping women’s engagement with mobile technologies. The figure below shows how the mobile gap emerges as girls enter puberty. The red line shows the percentage of females who use phones by age and the dotted gray line shows the percentage of married women. While the percentage of males who use a phone by age, represented by the blue line, continues to grow steadily before and after entering marriageable ages, growth in women’s phone usage slows and the gaps widen considerably as girls enter marrying age. This trajectory is suggestive of the power that norms related to purity and chastity have as girls approach marriage, and the continued perceived tradeoff between caretaking and other pursuits that women face once starting a family.

Evidence Provides Hope for Change

The norms and expectations we identified are persistent, deep-rooted, and shape the everyday experiences of women and girls in India. This leaves us with a hard question – what can be done about narrowing the gap in the face of such deeply rooted social structures? Do we have to try to change the norms themselves in order to initiate a widespread behavior change?

Our review of existing evidence shows that the answer is “not necessarily”. On the one hand, existing evidence shows that norms can be changed. This can happen through programs that target norms directly, like a community mobilization project in Uganda that significantly decreased the social acceptance of domestic violence, but it can also happen by promoting alternative norms more subtly, such as through television entertainment that glamorized smaller families and led to lower fertility rates in Brazil.

On the other hand, it is also possible to influence behavior without changing the norm. One approach is to provide high-powered incentives for people to change their behavior, like in a recent study of cash incentives for women to delay marriage in Bangladesh. An alternative approach is to give incentives for behavior change that are compatible with the normative context. For example, by providing bikes to school-aged girls, a program in the Indian state of Bihar was able to supersede social norms against girls traveling outside the village to attend school by providing a safer and faster means of transport.

Ultimately, identifying the right approach for a given context requires careful thought and experimentation. As we continue with our own project, we plan to use two randomized control trials to test alternative strategies for boosting women’s take up and use of mobile phones. So stay tuned for future posts on the interventions in the next phase of our study, and their impacts.

You must be logged in to post a comment.