As baby boomers age through their golden years, opportunities abound for researchers to advance the field of aging studies in the United States.

If a worldwide comparison of issues affecting the elderly is needed, only CESR has the numbers. An incredible number of numbers, at that.

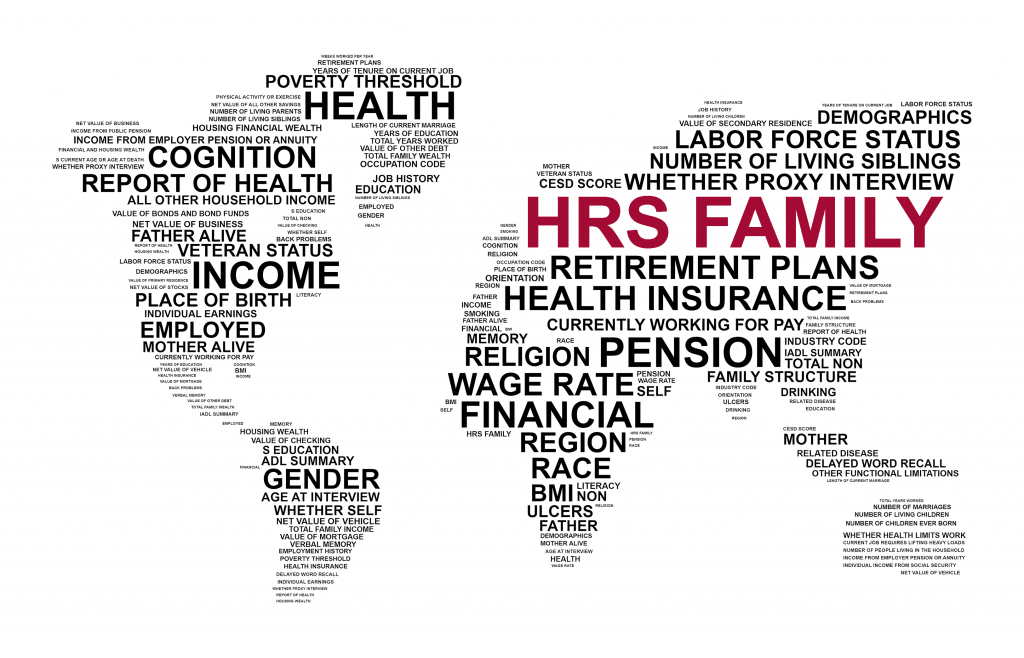

The Gateway to Global Aging is a database involving a dozen studies, cataloging 40 survey waves from 30 countries, representing more than half of the earth’s aging population. The information compiled ranges from simple demographics, to health of both body and mind, to economic factors like health care spending and work history, and support from family/social networks.

“All of these surveys are pretty complex,” said Drystan Phillips, a senior research programmer and project manager for CESR’s Program on Global Aging, Health and Policy. “One of the most interesting things about this data is the ability to pair physical health information with social science data.”

This wealth of data is why the Gateway can deliver, for example, a cross-country comparison of women’s wellbeing, as analyzed by Apoorva Jadhav, a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Michigan. In her upcoming paper, she is answering critical questions including: As a woman gets older, does she get more vulnerable to depression? How are her household’s economics faring?

Jadhav, before entering the field of aging research, was trained as a demographer, so she knows it can be complicated just studying Americans. However, using the Gateway data, she was able to mine this information both over time and across different countries, showing how an American woman fares compared to a British woman or a Japanese woman.

“It’s hard enough just to understand the [Health and Retirement Study], which has 11 waves,” Jadhav said. “Then you throw in China or Korea or Europe, it’s gets unwieldy really fast.”

It’s up to the Gateway team to wrestle the surveys into working order. Again, it’s a challenge made greater due to different contexts, different ways of asking questions, and different ways of compiling the answers.

But in the nine years following the Gateway’s establishment, the dataset has been honed into a powerful yet precise instrument.

“We really try to be a one-stop shop,” Phillips said. “You can come in and find the survey questions that are relevant to your research, you can use a harmonized dataset to easily put together an analysis. We have a publication search so you find out what’s also been published in that same area from that same study.”

Just a few of the publications that owe their findings to the Gateway include: a comparison of hypertension health care outcomes among older people in the U.S. and England, cross-national evaluations of later-life disability and health among women who were single mothers, and an inquiry into the training and wages of older workers in Europe.

The Gateway is also friendly to the casual user, hosting a page where a guest can compare basic facts about older populations across countries. (Did you know that in 2010, Chinese and Americans aged 55-64 held paid jobs at almost exactly the same rate? For the Chinese, 63.26 percent, with their counterparts in the U.S. coming in lower by less than a percentage point.)

Phillips says there are always plans for improving the Gateway: additional studies, better graphs and tables, mapping functions…

When Jadhav heard the team was thinking about adding the ability to produce heat maps, she blurted out, “Oh, I would like that!”

Jadhav is so appreciative of the dataset’s capabilities, not to mention the team’s help, that she’s become something of an evangelical about the Gateway: “It’s so good, I don’t think I even looked around to see what else is [available].”

Funding the Gateway is the National Institute on Aging, one of the National Institutes of Health.