In anticipation of this coming November 8th, the USC Dornsife / LA Times Presidential Election “Daybreak” poll has been following the voting intentions of approximately 3,000 Americans throughout the country. With a poll that tracks probabilities of a Clinton or Trump win in real time, many are watching. But from a behavioral science perspective, one of the most interesting questions in any election is not who will win, but why people are planning to vote the way that they are.

As a behavioral scientist at USC, I spend a lot of time thinking about why people behave the way that they do. This week, I turned my attention to the election and the “Daybreak” poll. “Daybreak” is not only innovative in its polling strategy, it is also innovative in the rich data that it collects on its respondents, who are part of USC’s Understanding America Study, an Internet panel of a representative sample of Americans whom we survey periodically.

“Daybreak” already breaks down voter intentions by background characteristics such as age, gender, race and educational level. From this, we can observe, for example, that women are more likely to support Clinton while men support Trump, that Whites are more likely to support Trump while African Americans and Hispanics are more likely to support Clinton, and that a higher level of education is associated with greater support for Clinton. But this can’t be the whole story – there is a great deal of variation even within these basic categories.

This brings me to one of the more unusual pieces of data collected within the UAS: personality traits. The UAS measures personality using the “Big Five”: a 44-item questionnaire that has been widely used in the social sciences over the past 20 years to measure five broad and stable traits of a person that are theorized to affect a range of behaviors.

Most people are not one trait or another; rather, research shows that everyone has each of the below traits to a greater or lesser extent. The five traits can be summarized as follows (adapted from John et al., 2008):

- Extraversion: Energetic approach to social activity.

- Agreeableness: Pro-social and communal orientation toward others.

- Conscientiousness: Socially prescribed impulse control that facilitates task and goal-oriented behavior, following rules and norms.

- Neuroticism: Negative emotionality, such as feeling anxious, nervous, sad or tense. (Sometimes referred to by its inverse, Emotional Stability).

- Openness to experience: Describes breadth, depth, originality and complexity of thought, coming up with novel ways to do things.

Research shows that these “Big Five” traits can predict job performance, health outcomes, and a variety of tastes and attitudes. Since the decision to vote is also linked to some extent to personality and preferences, the “Big Five” could also help us understand voter preferences and intentions.

The question I set out to answer is, do these personality traits, measured months or even years before this election cycle, have an association with respondents’ voting intentions in the 2016 Presidential election? And if an association exists, does it have any predictive power beyond, say, background characteristics or who the respondent voted for in the previous election? Since personality varies by individual, variations that can be measured with the “Big Five,” these traits could be one piece of the puzzle to help us answer why people vote the way they do.

It turns out that personality has a strong, significant association with voting intentions, even when controlling for factors such as age, race, gender, socio-economic status and prior voting behavior. This is interesting, particularly because the “Big Five” is an inventory of general personality traits – the questions do not incorporate political attitudes in any way.

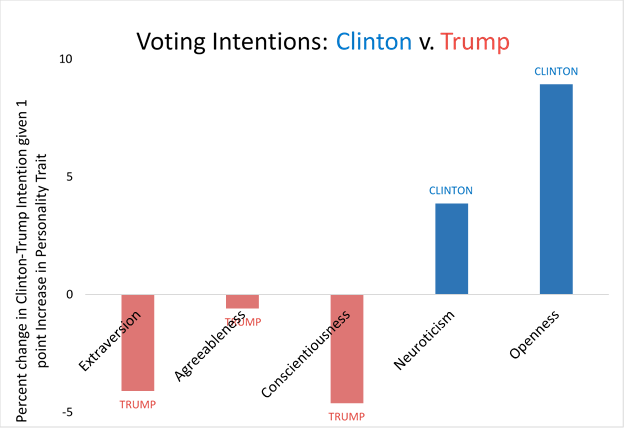

The figure below shows the estimates of the association of each trait with a Clinton versus Trump voting intention from a statistical analysis that controls for a variety of background characteristics and whether or not the respondent plans to vote in this election (see Data Appendix for more details). All traits but Agreeableness have a strong and statistically significant association with voting intentions. Higher degrees of Extraversion and Conscientiousness are associated with voting for Trump, while higher degrees of Neuroticism and Openness are associated with voting for Clinton. Interestingly enough, these results also hold when controlling for voting behavior in the last election (though the magnitude of the effect is muted).

Why might these traits affect voting behavior? To help answer this question, we can look to related research on the association between “Big Five” personality traits and political ideology. A summary has been written by Gerber et al. (2011). Related studies consistently find that Conscientiousness is associated with supporting conservative candidates, while Openness to Experience is associated with supporting liberal candidates, a result we also observe. Since Openness to Experience is associated with positive responses to change, researchers propose that individuals high on this trait would be more willing to support policies that may involve supporting new government involvement in the economy. On the other hand, Conscientiousness is associated with following social norms and achievement striving – hence, individuals high on this trait may reject liberal policies that may also be seen as undermining incentives for individual effort.

Gerber et al. (2010) also investigate the relationship between Emotional Stability (the opposite of Neuroticism) and political views. They find that people with higher Neuroticism are more likely to identify with liberalism, while people with higher Emotional Stability are more likely to be conservative. Along these lines, we find that individuals scoring higher on Neuroticism are more likely to support Clinton (hence, individuals scoring high on Emotional Stability are more likely to support Trump). As noted by Gerber et al. (2010), a possible reason for this result is that higher Neuroticism is also associated with greater worry about one’s economic future – and a greater projected reliance on social supports. Hence, people higher on Neuroticism may be more likely to support redistributive policies, which are also lined up with more liberal parties.

Regarding Extraversion, findings in the literature are mixed. When researchers do find a relationship, they tend to see that Extraversion is associated with conservative attitudes (we also observe that Extraversion is associated with support for Trump). The underlying reasons for this result remain difficult to identify.

Personality traits are thought to be stable over one’s lifetime. Since these traits are measured months or years prior to voting intentions, we might see this as suggestive evidence that different personalities cause people to vote in certain ways. However, a nascent series of research papers in political science have suggested an intriguing new explanation: another factor, namely, genetic predisposition, is proposed to affect both personality and voting behavior (Funk et al., 2012). The idea that genetics play a role in human behavior is also supported by research currently underway at the USC-CESR Behavioral and Health Genomics Center.

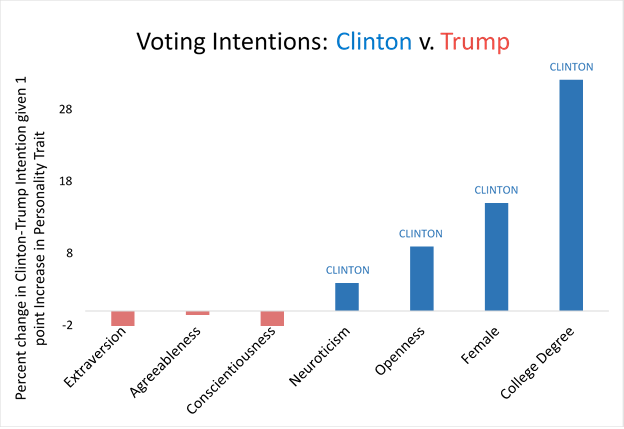

How can we put these measures into context? The next figure compares the results from the “Big Five” to two background characteristics that are also associated with a Clinton or Trump vote: gender and education level. Having a college degree increases the likelihood of voting for Clinton over Trump by 32 percentage points relative to no degree (having a professional degree increases it by 42 points, not pictured), while being female increases the likelihood of voting for Clinton over Trump by 14 percentage points. By comparison, Openness has the most predictive power out of all the other traits, since a 1 standard deviation increase in openness leads to a 9 percentage point increase in the likelihood of voting for Clinton over Trump. Keeping in mind that the personality traits are measured on a continuum (while gender and college completion are not), this shows that while personality traits certainly do play a meaningful role in understanding voting behavior, they are not the main predictors of voting intentions.

Even when accounting for all of these background characteristics, the role of personality, and previous voting behavior, we can still explain only about 15% of the variation in voting intentions. More work is needed to answer the question of why people vote the way that they do.

You must be logged in to post a comment.