An increasing number of patients prescribed oral drugs for advanced-stage cancer can now pick them up at the same place where they see their oncologist rather than travel to a specialty pharmacy or wait for them to arrive in the mail. This convenience is made possible through an emerging model that holds potential to significantly enhance cancer care by making treatment more accessible—but it may come with significant drawbacks.

The model, known as medically integrated dispensing, allows oncology practices to dispense oral anticancer drugs at their practices in onsite pharmacies. The potential benefits of medically integrated dispensing include:

- Better care coordination and patient monitoring

- Reduced time from diagnosis to treatment

- Lower barriers to medication uptake and adherence

- Averted toxicities and adverse drug reactions

- Fewer toxicity-related ED visits and hospitalizations.

These benefits could be offset, however, by the potential downsides. If oncologists profit from drugs dispensed by pharmacies at their practices, medically integrated dispensing could:

- Create incentives for inappropriate prescribing

- Create incentives for overprescribing

- Increase overall costs without increasing the value of care.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

To learn more about this little-studied care model, our team, in collaboration with researchers at the University of Southern California, Anthem, and HealthCore, designed a study to determine its prevalence. We created a novel dataset linking pharmacies to oncologists and their practices and analyzed national and state trends in the use of this model among community and hospital-based oncologists. We also examined the characteristics of the physicians adopting medically integrated dispensing and their patients.

Findings

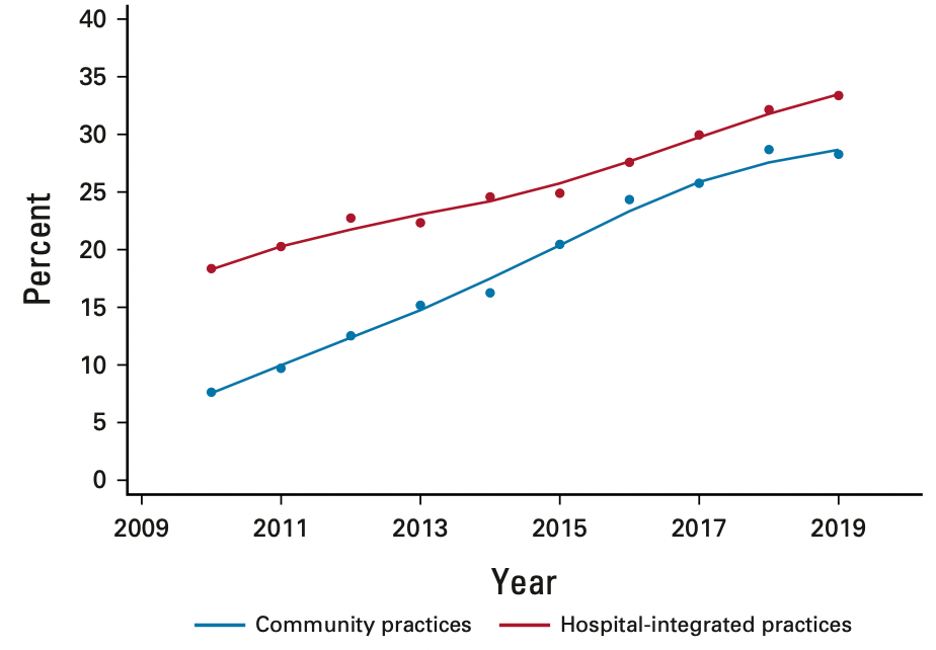

Between 2010 and 2019, medically integrated dispensing expanded significantly. The share of oncologists practicing in an office that dispenses medications increased by 151%, from 12.8% to 32.1%. Among community oncologists—those not affiliated with a hospital or health system and estimated to treat 55% of patients with cancer—dispensing rose 272%, from 7.6% to 28.3%.

The patients treated by oncologists in these dispensing practices were also different from patients treated by oncologists in nondispensing practices, having both more clinical and social risk factors. In particular, they were more clinically complex, whether commercially insured or Medicare insured. They also lived in areas with a higher share of Black residents. These findings indicated that as medically integrated dispensing expands, it may particularly affect those who are historically marginalized. Thus, quality of care differences between dispensing and nondispensing practices hold potential to impact health inequities, for better or worse.

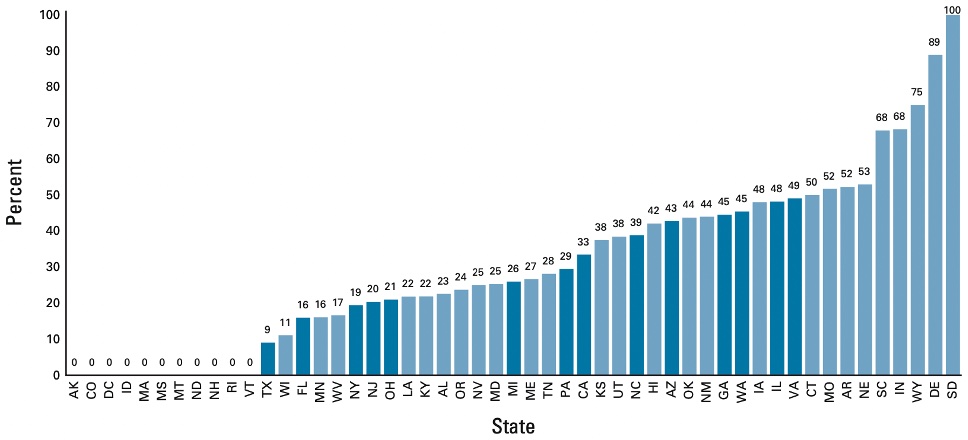

The share of oncologists engaged in medically integrated dispensing varied substantially across states, from 0% for community oncologists in some states to 50% or greater in nine states. These variations are likely due to a complex combination of factors. The most important factor may be state laws, some of which ban prescriber ownership of pharmacies or limit the size of their stake. Other state laws prohibit prescribers from dispensing medications at their practices or referring to facilities where they have a financial stake.

Implications

We are currently analyzing state laws and associated regulations to identify those with the greatest impact on medically integrated dispensing. We are using the differences in the laws to answer these questions: Do physicians change the types and quantity of drugs they prescribe when they adopt medically integrated dispensing? Do drug expenditures increase or decrease? Are patients able to start treatment sooner and better adhere to treatment?

We are also examining the effects of vertical integration—the merging of hospitals with physician practices. For example, currently, hospital-based practices are more likely to offer onsite pharmacies because of existing infrastructure, financial support from a parent health system, and powerful incentives from the federal 340B drug program. In addition, community oncology practices are driven to consolidate for financial viability; these consolidating practices are more likely to adopt medically integrated dispensing because of higher patient volumes and higher expected returns from a pharmacy.

Our forthcoming work will clarify the effect of pharmacy integration on physicians and patients and the policy tools that have the greatest leverage on physician-pharmacy integration.

The study, “Trends in Medically Integrated Dispensing Among Oncology Practices,” was funded by the National Institute for Health Care Management Foundation and published in the July 2022 issue of JCO Oncology Practice. Authors are Genevieve Kanter, Ravi Parikh, Michael Fisch, David Debono, Justin Bekelman, Yao Xu, Stephanie Schauder, Gosia Sylwestrzak, John Barron, Rebecca Cobb, Dima Qato, and Mireille Jacobson.

Data for this research was provided through the Penn LDI-Anthem partnership.

You must be logged in to post a comment.