Nearly three years ago, we formed a partnership with D. Brian Burghart, a journalist responsible for building the most comprehensive collection of police homicide[i] data in the country—titled Fatal Encounters. At that time, Burghart had meticulously assembled nearly 12,000 incidents of police homicides with plans to collect more cases back to the year 2000, while simultaneously collecting new cases as they occurred. Data from FE are compiled using a number of sources including: FOIA requests of police departments, open-source searches, crowd-sourcing, and use of official data to identify decedents. A protracted effort by Fatal Encounters has led to a nearly complete census of police homicides since 2000; 23,578 incidents have been tracked thru 2017.

This unprecedented data collection is nearly complete, and we are now in a position to make some general statements about police homicides in America, with a view to conducting a comprehensive examination of the causes and effects of this uniquely important public health problem.

Unofficial vs. Official Data

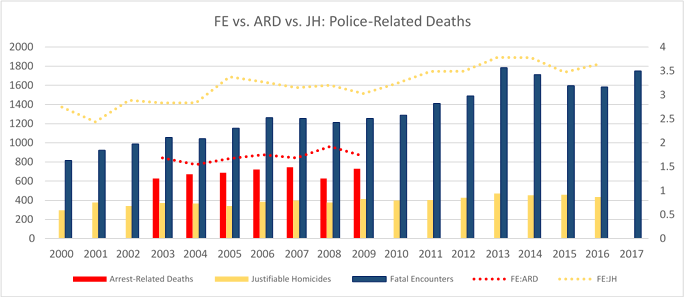

As noted in our prior post in this blog, official counts of police homicides are woefully incomplete. While all sources of data show general increases in police homicides from 2000-present, the Fatal Encounters (FE) data contain between 2- to 4- times as many police homicides as both the FBI’s “justifiable homicides” and the Bureau of Justice Statistics’ “Arrest Related Deaths” data[ii]. For example, in 2009, FE documents 1,157 police homicides while the FBI and BJS document 414 and 496, respectively (see Figure 1).

The undercount in the FBI (JH) and BJS (ARD) sources are due to both non-reporting of incidents as well as under-reporting among those who volunteer their data. In other words, while data is missing for those police departments that do not participate, incidents are also missing among those who do report.

Based on our FE data, police homicides seem to have peaked in 2013 (n=1,771), although 2017 (1,751) outpaced both 2015 (n=1,567) and 2016 (n=1,573). On average, law enforcement officers kill more than four civilians per day in the US, although only a few incidents receive national press coverage. It has been estimated elsewhere that law enforcement in Los Angeles County alone kill nearly one civilian every week.

Police Homicides as Share of Total Homicides

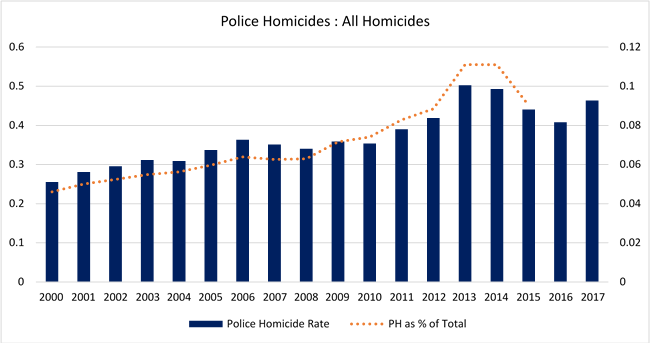

Figure 2 shows the police homicide rate per 100,000 US population (see left y-axis) as well as the proportion of police homicides relative to total homicides (see right y-axis). As presented, police homicides represent between 5 and 12% of all homicides in the country in any given year. We expect this to vary dramatically by geographic region and police department, but future analyses will quantify this more directly. Given falling crime rates over the past two decades (2015 and 2016 notwithstanding) and given increasing numbers of police homicides, the share of police homicides as a proportion of total homicides has steadily increased until 2013.

Police Homicides vs. Crime Rates

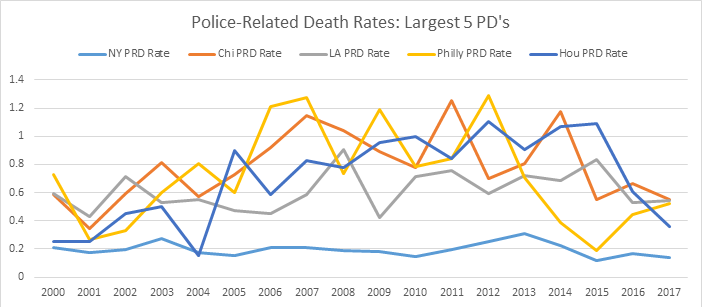

First, there appears to be wide variation in police-homicide rates (see Figure 3). It might surprise some to note that, once adjusted per capita, police homicide rates among NYPD are among the lowest of the Big 5 police departments. Adjusting for crime tells a bit of a more nuanced story.

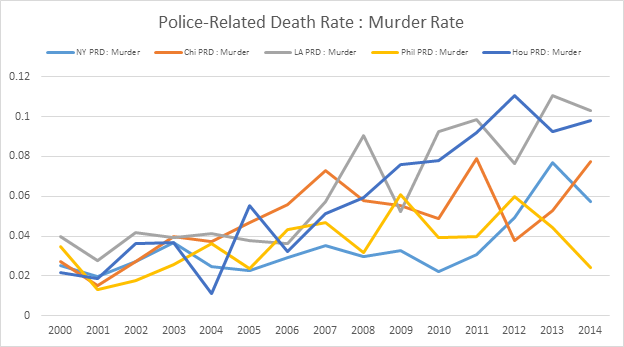

In figure 4, we adjust the police homicide rate for the murder rate (although things look generally the same adjusting for aggravated assault or violent crimes). A few things are worthy of noting here: 1) NYPD still maintains the lowest police-homicide rate, controlling for their relatively low murder rate, 2) Houston PD and LAPD exhibit some of the highest rates, net of the murder rate (or any violent crimes), and 3) police homicides have increased while violent crime and murders have decreased over time, leading to a general upward trend in both the gross police homicide rate and the crime-adjusted police homicide rate. This does not bode well for the future, unless we believe that the activities leading to police homicides are becoming increasingly unique and unrelated to overall crime rates.

Future Research

Our future research will attempt to answer questions related to police-department policies and police homicides by creating two police homicide databases using data collected by the Fatal Encounters project. We will merge FE police homicide data with several public data sources that collect information about: 1) police-department characteristics and policy, 2) civilian crime, 3) assaults/killing of police officers, 4) socio-demographic data describing US neighborhoods, 5) gun thefts and guns per capita, and 6) emergency department availability. Our national police homicide database will be used to examine which police department policies are associated with lower rates of police homicides. Our project will also create a GIS database which provides geo-locations of all police homicides in order to study the independent effect of police homicides on population health, health disparities, community well-being, and police/community relations.

The first step in reducing police homicides was to document the extent of the problem. In the spirit of true investigative journalism, Mr. Burghart of Fatal Encounters has made a herculean effort in documenting all police homicides from 2000 to the present. We are hoping that our growing partnership with him and our detailed visions for needed research will lead to future grant funding[iii] so that we can begin to explore the causes and effects of police homicides, as part of larger efforts to reduce both police and civilian violence in the United States.

If you are interested in funding our project, please email: brianfin@usc.edu or d.brian@fatalencounters.org

[i] Homicide is defined as “one human killing another human”, and we do not assign any moral or legal import to such a term. Our study of police homicides includes police killing civilians who are engaged in both legal and illegal activities—virtually all of which are legally adjudicated as justifiable homicide, and not murder or manslaughter.

[ii] We should note that differences between sources are not simply definitional. Fatal Encounters includes only homicides that result from deaths occurring during an arrest scenario, almost all of which are firearm related.

[iii] This project is being partially supported by NIH Grant #R01 HD093382.

You must be logged in to post a comment.