Story after tragic story has emerged about the havoc that the COVID-19 pandemic has inflicted on the mental health of children and teens. From losing family members to disease, to school closures and continued school disruptions, to limited peer interactions and fractured social lives, the possible factors influencing worsening mental health are numerous. Though experts have been careful to emphasize that the COVID pandemic exacerbated an already existing mental health crisis, a consistent trend both inside and outside the United States is that girls seem to have been disproportionately affected compared to boys.

In April 2022, researchers at USC’s Center for Economic and Social Research asked a nationally representative sample of households to complete a survey (the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire [SDQ]) about the mental health of a child in their home (we selected one of their children at random if they had more than one) as part of the Understanding America Study (UAS). This psychometrically validated instrument is one of the most commonly used tools for screening mental health in children and adolescents. Comparing results to those from the same battery of questions posed to a different, but also nationally representative, sample in 2013 (He et. al) reveals interesting and important patterns about the changes underlying worsening mental health over the last decade.[1]

Our findings document worsening mental health since 2013 among both boys and girls, with results shedding light on areas of particular concern and a troubling pattern among girls. With continued tracking over time, we hope to help inform interventions and outreach, particularly in schools, that can help mitigate the ongoing mental health crisis facing our nation’s youth.

Small decline in overall mental health measure masks important changes

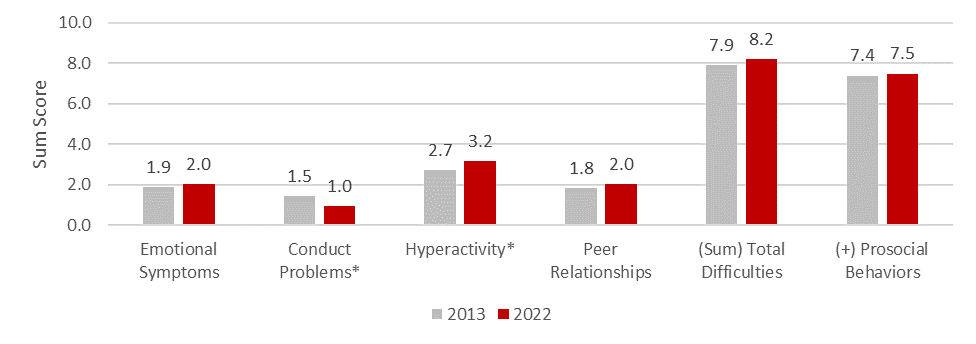

Perhaps surprisingly, the overall mental health “difficulties” score (higher scores represent more negative experiences) in 2022 was only a bit higher than it was in 2013 (8.2 compared to 7.9). However, this subtle change at the overall level masks opposing patterns in particular areas, or domains, of mental health (Figure 1). First, there was a statistically significant increase in the Hyperactivity domain (e.g., restless, overactive, easily distracted, fidgeting/squirming), accompanied by a statistically significant decrease in the Conduct Problems domain (e.g., often loses temper, fights with other youth, lies or cheats). In other words, when reporting on the mental health of a child, parents in 2022 reported more restlessness, distraction, fidgeting-type behaviors than a group of parents reported on their children in 2013; but they also reported fewer fights, lying, cheating and losing temper-like behaviors.

*Significant difference between the average score in 2013 and the average score in 2022 (p<.05)

We also observed higher scores (i.e., more difficulties) in the Emotional Symptoms domain and the Peer Relationships domain, though these changes were smaller and not statistically significant.

More negative scores for girls than for boys

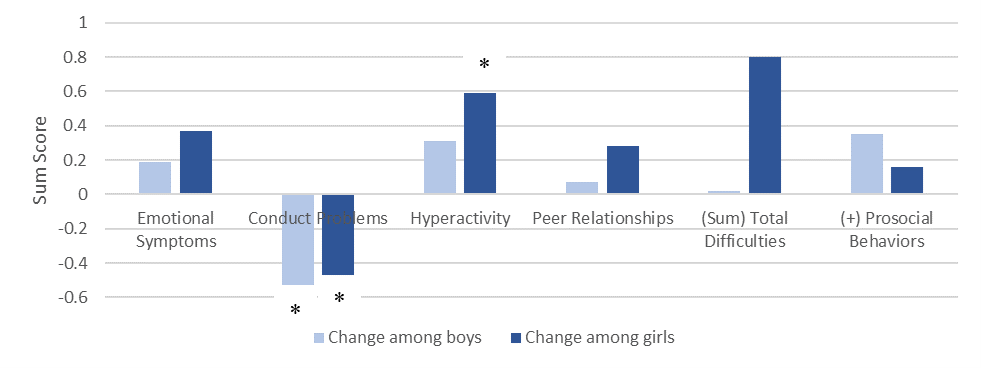

When looking at results by gender of the child, we see similar drops in the Conduct Problems domain compared to the 2013 snapshot, and similar increases in the Hyperactivity domain for both boys and girls (Figure 2). Notably, though, the magnitude of change for girls was always worse than for boys – in all domains that compose the scale. Difficulty scores were larger for girls than boys in the Emotional Symptoms, Hyperactivity, and Peer Relationships domains, and the relative positive lower score in the Conduct Problems domain was smaller for girls. Further exacerbating concerns about girls’ mental health, the relative protective increase in the Prosocial Behaviors domain (the “Strengths” of the SDQ) was smaller for girls than for boys. Though these patterns were not always statistically significant, they align with recent findings that girls’ mental health is in a heightened state of crisis.

Girls suffering more than boys in 2022, as evidenced by anxiety and depression items

As noted, scores for girls in the difficulty domains were higher (worse) in 2022 than in 2013. When looking only at 2022 data (Table 1), girls’ Emotional Symptoms score was significantly higher (worse) than boys’. This domain includes items such as “often seems worried”, “has many fears”, and “often unhappy, depressed or tearful”. In 2022 girls scored almost one full point higher (worse) on this domain scale compared to boys. Boys are struggling more than girls in the area of Hyperactivity (i.e., Hyperactivity scores were higher (worse) for boys), but the difference between boys and girls on that domain is almost half what it is for the Emotional Symptoms domain. Importantly, girls score significantly higher (better) than boys on the potentially protective strength domain of prosocial behaviors (7.83 for girls compared to 7.22 for boys), though as shown above, this domain score increased more (improved more) for boys than it did for girls since 2013.

Table 1. Differences in domain scores between girls and boys in 2022

| Boys | Girls | Difference | |

| (Sum) Total Difficulties | 7.92 | 8.36 | .44 |

| Emotional Symptoms | 1.53 | 2.45 | .92* |

| Conduct Problems | 0.99 | 0.92 | -.07 |

| Hyperactivity | 3.38 | 2.97 | -.41 |

| Peer Relationships | 2.03 | 1.99 | -.04 |

| (+) Prosocial Behaviors | 7.22 | 7.83 | .61* |

*Significant difference between boys and girls in 2022, p<.05

Results can inform targeting of mental health strategies and resources

Our lens on youth mental health post-pandemic can inform strategies for allocating large-scale investments in youth mental health services in schools. There is a clear need to consider the experiences of girls, whose parents are reporting significantly more reports of depression and anxiety today for their daughters compared to 2013. These results resonate with the terrifying statistics frequently cited relating to the increase in suicide attempts and mental health-related emergency hospital visits among girls. Not only have reports of girls’ symptoms increased in every negative way, the one positive decrease observed (in the Conduct Problems domain) was smaller for girls than it was for boys. We hope these results can be used by mental health experts, school counselors, parents, and others who can learn from these changing patterns, informing interventions and preventative measures.

We plan to re-administer the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire periodically over the next two years to the same sample of households, about the same children, allowing us to build within-person measures of mental health and behavior difficulties as they evolve over time, as well as exploring the relationship between differing school-based experiences during the COVID recovery period and related changes reflected in the SDQ over time. We believe these data will contribute productively to discussions of the evolving mental health of students in the post-reopening K-12 school system. It is essential to elevate discussion of the effects of the pandemic on children’s and teens’ mental health to support strong, data-driven policies that have the potential to allocate mental health resources where they are most needed.

[1] We limited our 2022 sample to only parent respondents of children between the ages of 13-18 to maximize similarity to the 2013 sample. The overall 2022 sample is based on a probability-based survey method and is nationally representative. The subgroup of children aged 13-18 is compositionally similar by race/ethnicity, household income, and household education level to the overall nationally representative sample, and matches the age range of the 2013 group.

You must be logged in to post a comment.