Medicare Advantage (MA) enrollment has increased rapidly over time. New research is helping to quantify a key driver underpinning this growth—MA’s greater financial generosity compared to traditional Medicare—and what that may mean for program reform. As policymakers consider reforms that might lower federal spending by reducing payments to MA plans, this research highlights the impact such changes could have on beneficiaries’ costs.

Nearly 33 million Medicare beneficiaries, or 54% of the Medicare-eligible population, now enroll in MA plans. Much of this growth is likely attributable to MA plans’ ability to cover extra benefits, like dental and vision, and offer enhanced financial generosity for beneficiaries, like reduced premiums and cost sharing. In Health Affairs, we quantify just how large this financial advantage is to prospective enrollees relative to other Medicare coverage options.

To do so, we used the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services’ (CMS) own projections of the financial generosity of each option available to beneficiaries. CMS measures how much a typical beneficiary would spend on premiums and cost sharing under different MA plans and under traditional Medicare, using a fixed basket of health care services. We use these data to capture how much enrollees could expect to save if they picked an MA plan instead of traditional Medicare, both with and without Medigap coverage. (Medigap coverage is an optional, supplemental policy traditional Medicare enrollees can purchase to cover some out-of-pocket costs.)

The differences were substantial.

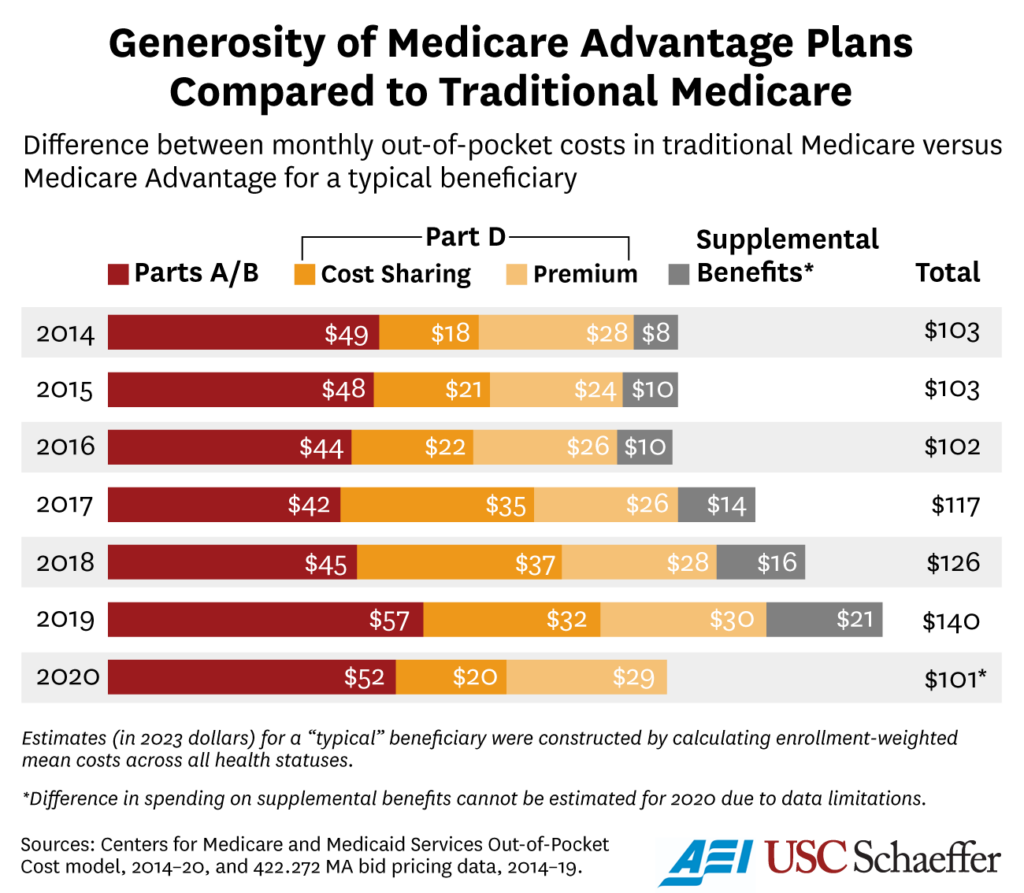

On average, a typical enrollee could expect to save 18-24% on out-of-pocket costs by picking an MA plan over traditional Medicare—an amount equivalent to nearly $140 per month. More than 40% of these savings are concentrated in drug coverage, which is likely particularly salient to consumers.

The absolute savings were larger for enrollees in worse health (who tend to use more health care services) and for people who picked HMO plans (rather than PPO plans) within MA.

On average, the out-of-pocket cost difference between MA and traditional Medicare persisted even when traditional Medicare was paired with a Medigap plan. This, perhaps surprising, result reflects the fact that premiums in Medigap, which unlike other Medicare plans are not federally subsidized, are priced to offset expected reductions in cost sharing (plus any administrative loading) across the market.

However, the impact of Medigap on expected out-of-pocket costs varies across beneficiaries depending on their health status. For sicker beneficiaries, Medigap reduces expected out-of-pocket costs because they pay less in Medigap premiums than they receive in out-of-pocket cost reductions in a given year—and vice versa for healthy enrollees.

These cost differences may help to explain increasing MA enrollment. Notably, the projected total out-of-pocket costs used in this analysis were shown to beneficiaries enrolling via Medicare Plan Finder through 2020. This information may have directly affected the choices of some enrollees.

This extra financial generosity of MA plans reflects two compounding forces: MA plans are better at constraining costs in certain ways than traditional Medicare while also being paid more than traditional Medicare to cover the same enrollee.

The Medicare Payment Advisory Commission recently estimated that the cost of covering MA enrollees was around 17% higher than for an equivalent traditional Medicare beneficiary in 2019. Many have argued in favor of reducing these “overpayments” through various mechanisms. While the fiscal benefits of doing so are clear, they need to be weighed against a reduction in enrollee benefits that would likely follow.

Our work shows that beneficiaries benefit from higher MA reimbursement via lower out-of-pocket spending—including reductions in premiums—and potentially more generous benefits along other dimensions. A back-of-the-envelope calculation suggests that the beneficiary cost reductions associated with enrolling in MA account for around 75% of these extra payments.

While not an endorsement of current spending levels, this does suggest that enrollees may have higher out-of-pocket costs if MA payments were set at parity to fee-for-service Medicare payment levels. As policymakers debate reforms to the MA program, this presents a political conundrum. With more than half of Medicare beneficiaries now enrolled in MA, there are tens of millions of beneficiaries for whom increasing out-of-pocket costs would be unpopular.

At a minimum, policymakers should recognize that MA reforms involve meaningful tradeoffs. This reality may also argue for a systematic approach to reforms that allows policymakers to learn more about how sensitive these benefits are to incremental changes in spending. Doing so could allow for a better calibrated policy informed by key tradeoffs.

Benedic Ippolito is a senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute. Erin Trish is co-director of the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics and associate professor at the USC Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. Boris Vabson is a researcher at Harvard Medical School, a nonresident scholar at the Schaeffer Center and a nonresident fellow at AEI.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

You must be logged in to post a comment.