Experts who lead the Understanding America Study reflect on surveying Americans during the 2020 election cycle.

Today, on Election Day, we thought we’d reflect on our poll experience collecting data in the Understanding America Study this election cycle. This establishes something of a tradition, as we reflected on our experiences of being an outlier poll after the 2016 election here.

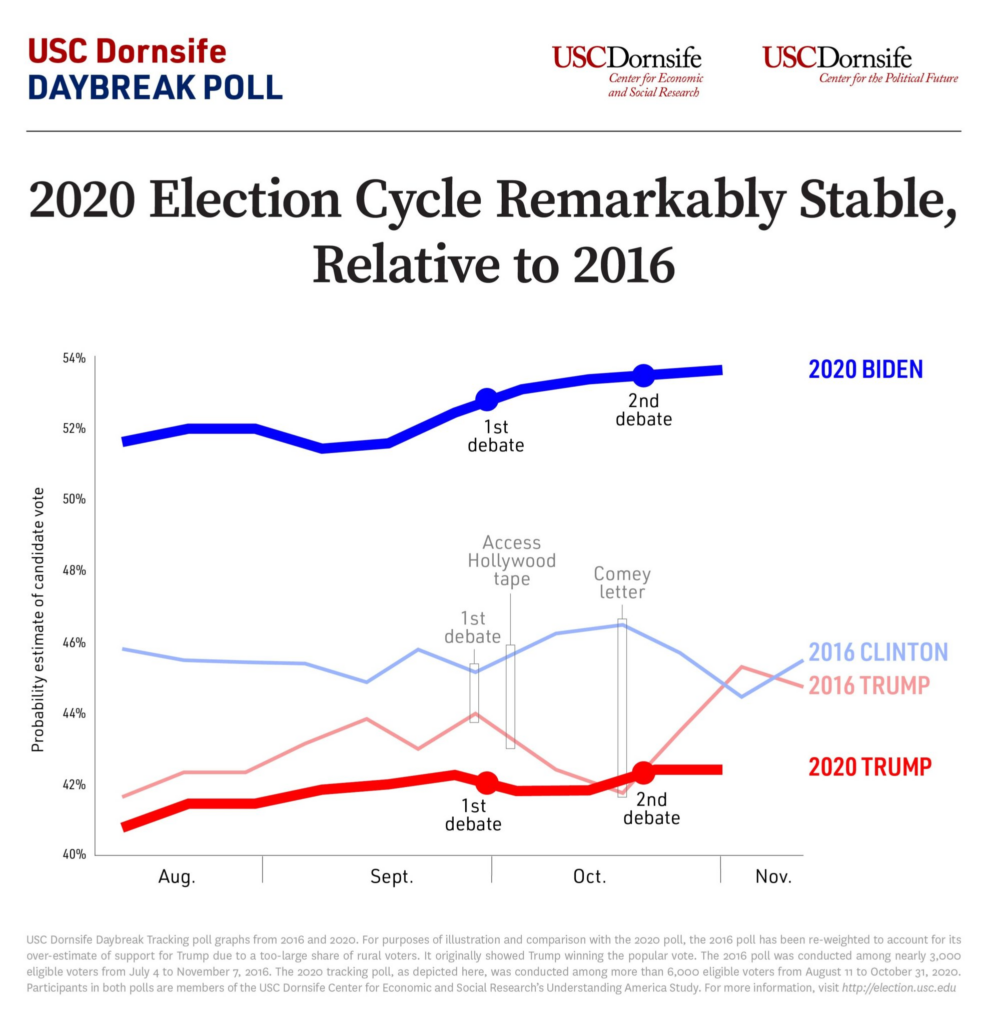

Many of us remember how the 2016 pre-election season was filled with tumultuous news events that felt like a series of earthquakes and aftershocks: Wikileak hacked the DMC, Trump and Billy Bush talked shop, Clinton referred to some Trump supporters as “deplorables,” and Comey wrote to Congress about Clinton’s use of a personal email server.

These events impacted the results of our 2016 Daybreak tracking poll, shifting it like a heat map toward Clinton or Trump, as each event registered in voter consciousness.

2020 has had its share of events as well. A global pandemic, the President’s response to it, and the resulting impact on the economy, political divisions, and health disrupted the country starting in March. The police killing of George Floyd on Memorial Day Weekend set off weeks of protests. In July it was announced that the U.S. Postal Service made cutbacks, potentially endangering its ability to handle an increase in mail-in voting. In August, Biden chose Kamala Harris as his running mate, the first woman of color to ever be part of a major party ticket. Some of Trump’s tax records were released by the New York Times at the end of September. Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg died in October, and the nomination of her replacement involved a super-spreader event at the White House that coincided with the President, Vice President, and other staff becoming infected with COVID-19. Not to mention both party conventions were conducted virtually for the first time.

None of these events shifted the point spread in our 2020 tracking poll more than a point or two.

Do we all just have “news fatigue,” in addition to our COVID fatigue? Can nothing shock us anymore? Pew Research Center was documenting signs of this in February. In August they found that 55% of social media users are tired of political posts and discussions.

A recent study released by the American Psychological Association found that the division, polarization, and perhaps residual anxiety of deflated election expectations from 2016 in combination with the COVID-19 pandemic seem to be wreaking havoc on our mental state. In our own COVID-19 study we find people report limiting news, downloading wellness apps, and drinking more.

Voters across parties are anxious about what will happen on and after election day, which has been fueled by rhetoric casting doubt on the election. Donald Trump has said he will fight to end the vote count after election day, and Joe Biden responded by saying that Trump will not be allowed to steal the election. In our poll, members of both parties predicted that the candidates are likely to contest the election and see a high likelihood that increased violence will follow. More than two-thirds of voters associated with each of the two major parties said that they not only have an unfavorable view of members of the other party but see them as a threat to the nation’s well-being.

In our poll, more than two-thirds of voters associated with each of the two major parties said that they not only have an unfavorable view of members of the other party but see them as a threat to the nation’s well-being.

Adding to the anxiety levels is a distrust of polls. In 2016, national polls mostly correctly predicted Clinton’s lead in the popular vote (notable exceptions included ours) but when election day ended, Trump had lost the popular vote but won the election in the Electoral College. The country was shocked by the fairly rare mismatch between the two election outcomes (last time was in 2000) and blamed the polls and the media for misleading the public.

We participated in many interviews asking us about the “Death of Polling” after 2016. The American Association for Public Opinion Research conducted an investigation of 2016 polling, and in its subsequent report noted that national polls were as accurate as in other election years, but many state polls had failed to account in their samples for an undercount of low education voters for Trump, and missed the mark. Our own internal investigation revealed that our 2016 overstatement of Trump vote was attributable to a high proportion of rural voters in our sample.

This year the Dornsife Daybreak tracking poll ended with a 10.9 -point Biden lead, two and a half points wider than the 8.4 point spread in Nate Cohn’s average of National polls. The poll is not predicting a winner in the electoral college vote because we do not have a sufficient sample size in each state.

Our USC colleague Wandi Bruine de Bruin and her collaborators at the Santa Fe Research Institute Mirta Galesic and Henrik Olsson, and Drazen Prelec of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, have added their Social Circle questions to our poll again this year, as they did in 2016. Their method asks voters to predict who their friend and family will vote for, and how their state will vote in the election. These questions have resulted in close estimates of the outcome in a number of previous elections in the U.S. and other countries (France, Sweden, The Netherlands).

Interestingly, their models also predicted Trump’s 2016 electoral college win. This year, their social circle and prediction models are predicting a tighter race than we see in models based on voters’ own votes, and they again predict a Trump win in the electoral college. An important caveat the team notes in a recent Q&A about their models is that this pandemic may make us less in touch with each other, and the surprise Trump victory in 2016 may also have an influence on how people think their social circles, and their states, might vote.

To find out which polls or models were accurate, and which were not this year, we will have to wait, just like everyone else.

You must be logged in to post a comment.