As of February 2021, and excluding those already vaccinated, more than half of all U.S. adults (56%) planned to get vaccinated for COVID-19. This is according to February 2021 findings from the nationally representative Understanding Coronavirus in America Tracking Survey conducted by the USC’s Center for Social and Economic Research. However, people’s willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccination varies by race, ethnicity, age, education, income, gender and other demographic factors.

The Willing, Unwilling and Unsure

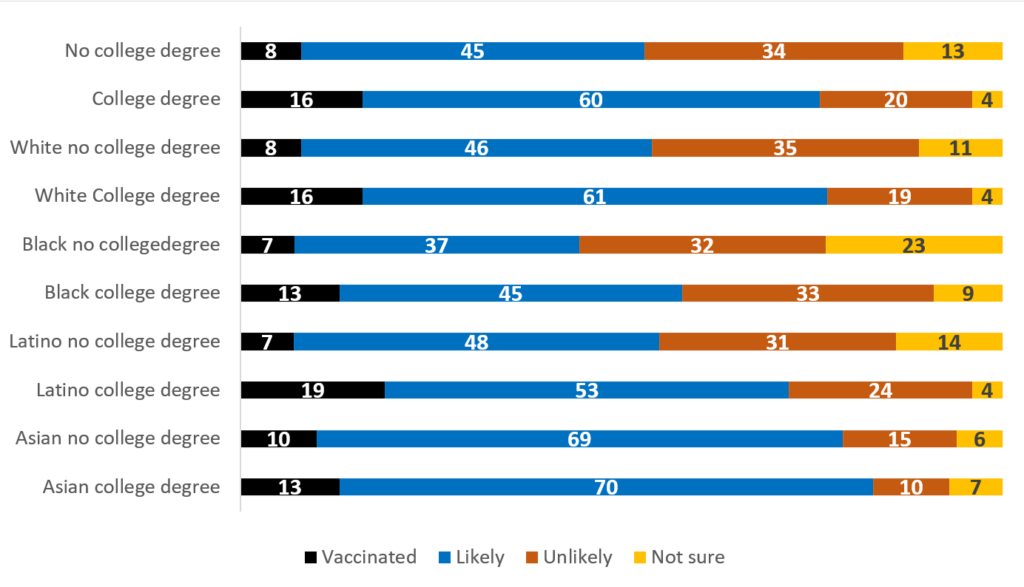

While the survey finds that racial and ethnic differences in vaccine hesitancy persist, level of education now has a stronger effect on people’s willingness to get the vaccine. The only exception may be people of Asian descent who—regardless of educational level—indicate a high level of willingness to get vaccinated.

Overall, at the time of the survey, 76% of U.S. adults with at least a bachelor’s degree had been vaccinated or planned to get vaccinated, compared to just over half of adults (53%) with less education (Figure 1). In other words, a college degree is associated with a 43% increase in the likelihood that someone plans to get the vaccine. This difference by education level is now larger than the difference in willingness to vaccinate now observed between white and Black adults (32%) and the difference now observed between white and Latino adults (3%).

However, in some cases, racial and ethnic differences in willingness to get a COVID-19 vaccination outweigh the effect of educational level. For example, the share of adults without a college degree who are unlikely to get vaccinated is similar among Blacks as it is among whites (32% and 35% respectively), but the share of adults without a degree who are unsure about getting vaccinated is much higher among Blacks (23%) than among whites (11%).

Figure 1: U.S. Adults Aged 18 and Older, Vaccinated and Willingness to Get Vaccinated, by Race/Ethnicity and Education

Vaccine Hesitancy and Equitable Access

As U.S. vaccine supplies increase, ensuring that higher-risk people get vaccinated as quickly as possible is a public health priority. Racial and ethnic minorities, for example, face greater risks of becoming severely ill or dying from COVID-19, largely because they are more likely to have underlying health conditions and to live and work in spaces that increase their risk of infection. However, in the 23 states reporting vaccination data by race and ethnicity, almost without exception, Black and Latino people had received smaller shares of vaccinations compared to their shares of COVID-19 cases and deaths and compared to their proportions of the total population. Likewise, people with lower levels of educational attainment are more likely to experience financial insecurity, live in overcrowded housing, work in frontline jobs, and lack access to adequate health care—all factors that increase their likelihood of contracting or dying from COVID-19. While increasing physical access to vaccines in underserved communities is critical to more equitable vaccine distribution, policymakers also should consider other factors, such as education, that can affect people’s willingness to get vaccinated.

Vaccine Attitudes and Education

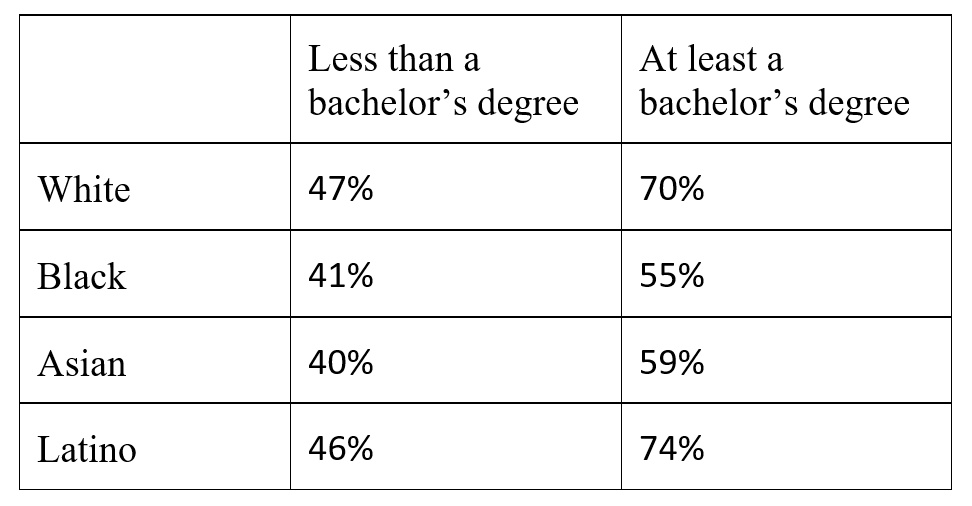

Our survey also finds that people with lower levels of education are less likely to know someone who has been vaccinated and generally are less trusting of the vaccines—both factors that may influence their willingness to get vaccinated. On a range of measures related to vaccine experiences and attitudes, including trust in the vaccine approval process and assessing the risk of serious side effects, people’s level of education plays a big role, according to our survey findings. For example, 54% of U.S. adults overall know a friend or family member who has been vaccinated, but U.S. adults with a bachelor’s degree are much more likely to know someone who has been vaccinated (69%), compared to those with less education (46%).

Differences by educational level also vary across racial and ethnic groups. For example, 74% of Latino people with a bachelor’s degree know someone who has been vaccinated, compared to 46% of Latinos with less education (Table 1). In contrast, only 55% of Black people with a bachelor’s degree know someone who has been vaccinated, compared to 41% of those with less education.

Table 1: U.S. Adults Aged 18 and Older Who Know a Friend or Family Member Who Has Been Vaccinated, by Race/Ethnicity and Education

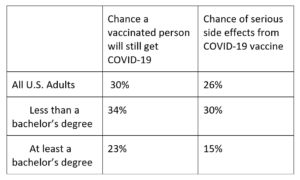

Both of the currently available vaccines are highly effective, reducing the risk of COVID-19 by about 95%, with minimal side effects—the most common being pain at the site of injection. Yet, U.S. adults vastly underestimate the effectiveness of the COVID-19 vaccines and overestimate the chance for serious side effects from the vaccines. Overall, U.S. adults believe there is a 30% chance that someone who has been vaccinated will still get COVID-19 and a 26% chance of serious side effects from the vaccine.

Again, educational level is a significant factor in people’s views about vaccine safety and efficacy. On average, U.S. adults with at least a bachelor’s degree view the vaccine as much safer and more effective than those with less education. For example, people with a bachelor’s degree believe there is a 23% chance that a vaccinated person will still get COVID-19, while those with less education believe there is a 34% chance. Similarly, people with a college degree believe there is about a 15% chance for a serious side effect from the vaccine, while those with less education believe the risk is more than double at 31%.

Table 2: U.S. Adults Aged 18 and Older Estimates of COVID-19 Effectiveness and Serious Side Effects, by Education

Implications

Earlier in the pandemic, race and ethnicity played a larger role in people’s attitudes about a COVID-19 vaccine, but now differences in educational levels in many cases have a greater effect on people’s willingness to get vaccinated. The most recent and almost real-time findings from the Understanding Coronavirus in America Tracking Study indicate that the educational gap in willingness to get vaccinated requires policy attention. As such, policymakers should consider tailoring vaccine awareness campaigns that emphasize the safety and effectiveness of COVID-19 vaccines to the public, especially those without college degrees.

For now, a limited supply of COVID-19 vaccine is the greatest factor hampering vaccine uptake by U.S. adults, with almost six in 10 saying they plan to get vaccinated. As vaccine supply increases, and once access inequities are addressed, the issue of overcoming vaccine hesitancy likely will move to the forefront of the policy agenda both nationally and in the states. Designing effective strategies to encourage people to get vaccinated will be key to increasing uptake and generating community protection against the coronavirus via widespread vaccination.

About the Survey

The data was collected from participants in the Understanding America Study (UAS), which is a nationally representative, probability-based online panel of adults who answer survey questions in the Understanding Coronavirus in America Tracking survey every two weeks, since March 2020.

Findings in this release are based on 6,231 participants who responded between Jan. 20, 2021, and Feb. 16, 2021. Margin of sampling error is +/- 1 percentage point for the national sample, +/-2 percentage points for the education subgroups. Margins of sampling error may be higher for race and ethnicity sub-groups, and are available, along with results of the full survey, in the survey’s topline and crosstab reports, on the UAS Covid-19 pages.

Graphs that are updated daily and more information on how the survey was conducted, as well as links to reports and data are available at covid19pulse.usc.edu.

You must be logged in to post a comment.