Racism targeted at Asians and Asian Americans has grown since the outbreak of the novel coronavirus. COVID-19, which originated in and devastated parts of China, has spread to new countries and the media, including CNN, The New York Times, the New Yorker, and The Wall Street Journal, have documented the growing number of discriminatory incidents. As quantitative social scientists working at USC’s Dornsife Center for Economic and Social Research (CESR), we were interested in determining whether these were isolated incidents or just the tip of the iceberg. Further, we wanted to know whether acts of racism related to the virus were restricted to Asian Americans or extended to other racial and ethnic groups that often bear the brunt of discriminatory treatment in America. We turned to the Understanding America Study to find our answers.

Between March 10 and March 21, CESR conducted a nationally-representative survey on the public perception and response to the coronavirus pandemic. We asked survey respondents whether they felt threatened or harassed, or perceived others as being afraid of them due to people thinking they might have the coronavirus. We also asked if they were treated with less courtesy and respect than others, or if they received poorer service at restaurants and stores due to the same reason. A total of 6,238 American adults completed the survey and answered these questions, including 4,130 non-Hispanic whites, 462 non-Hispanic blacks, 311 Asians, 1,012 Hispanics, and 323 people in other racial and ethnic groups. More findings and information about the methodology can be found here.

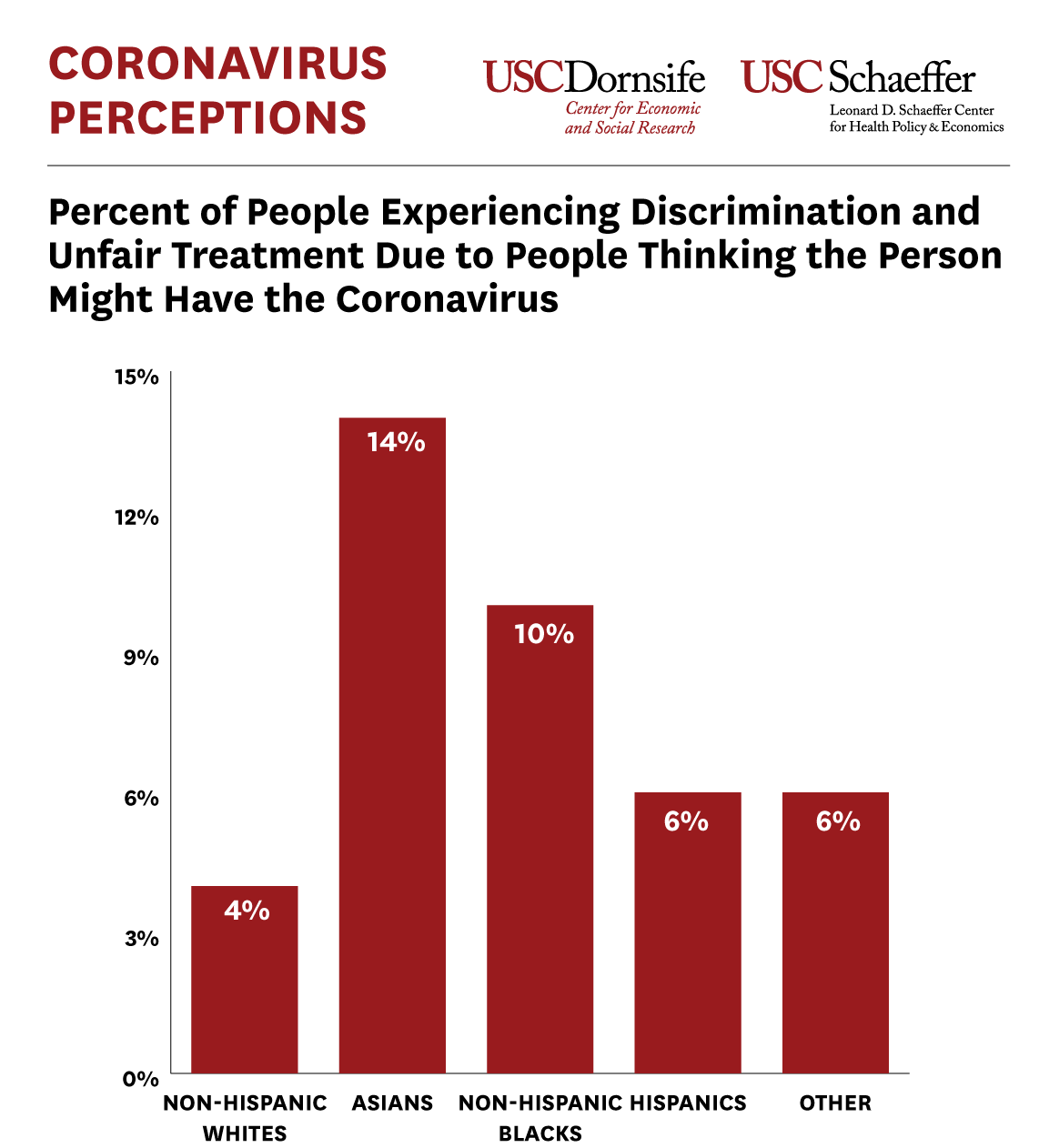

We found that Asian and African Americans were more likely to experience at least one form of discrimination and unfair treatment due to other people thinking they might have the coronavirus, compared to other racial and ethnic groups, albeit the overall prevalence is currently low. Our data show that 14 percent of Asians and 10 percent of non-Hispanic blacks had such experiences, as opposed to 4 percent of non-Hispanic whites, 6 percent of Hispanics and 6 percent of people in other racial and ethnic groups.

We wonder: is what we observed in the coronavirus pandemic essentially a carry-over from people’s day-to-day life in the past? What role do demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of a person play in this observation?

We wonder: is what we observed in the coronavirus pandemic essentially a carry-over from people’s day-to-day life in the past? What role do demographic and socioeconomic characteristics of a person play in this observation?

Between December 21, 2018 and February 28, 2019, the same panel of respondents participated in a prior survey, and were asked if they had ever been treated unfairly or been hassled or made to feel inferior due to their or their parents’ education, income, job or possessions (e.g., clothes, car, etc.). We consider these data a reasonable description of their day-to-day experience on discrimination and mistreatment before the coronavirus pandemic.

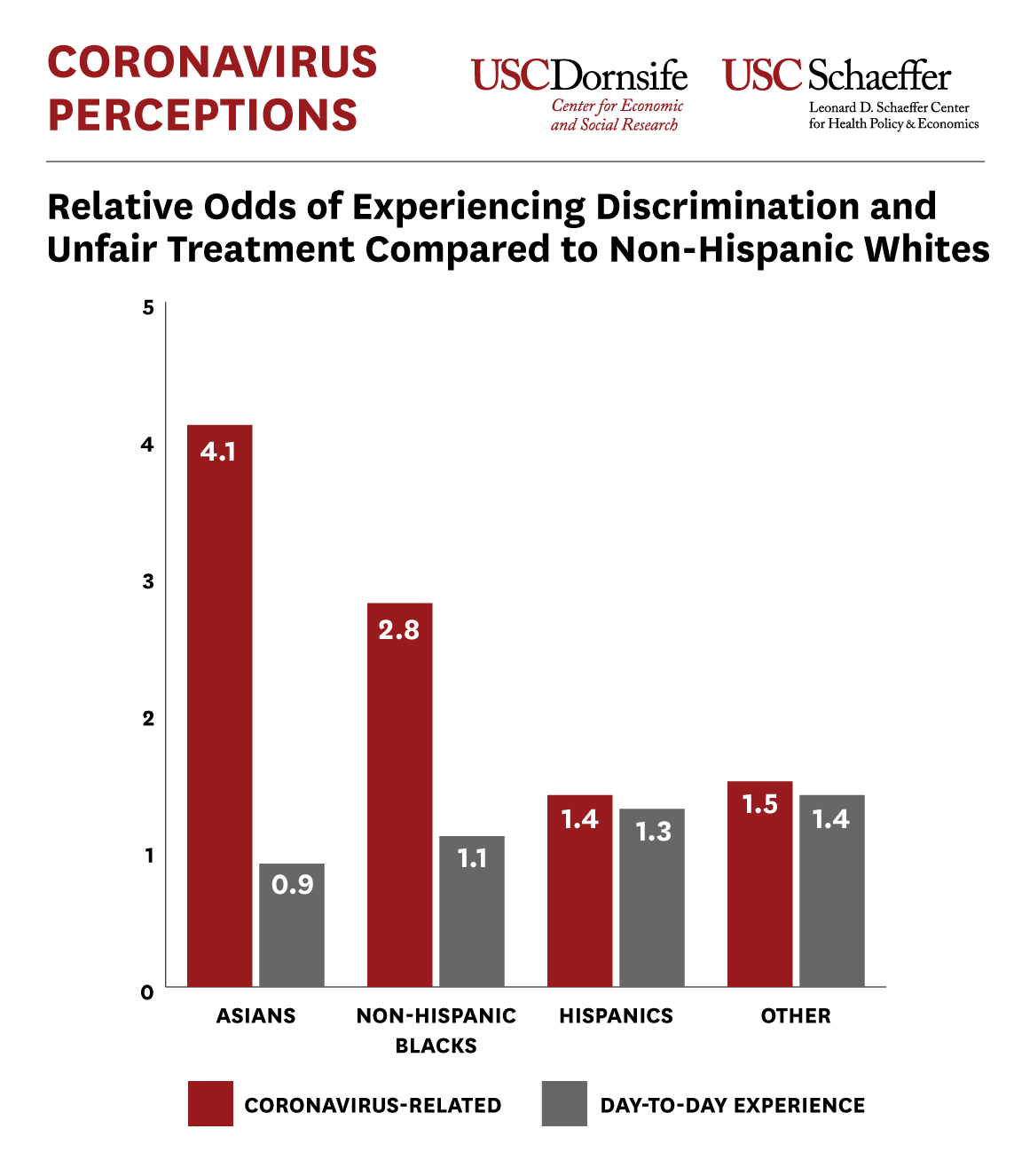

Using a logistic regression, we controlled for this prior day-to-day experience, as well as demographic and socioeconomic characteristics including age, gender, education and household income. The odds were four times higher for Asians and almost three times higher for non-Hispanic blacks than non-Hispanic whites to have reported perceived discrimination amid the coronavirus pandemic. In contrast, the odds for Asians and non-Hispanic blacks to experience day-to-day discrimination and mistreatment were similar to the odds for non-Hispanic whites, after adjusting for the demographic and socioeconomic characteristics. These findings suggest that this form of discrimination and mistreatment amid the coronavirus is new and distinct.

We further controlled for respondents’ self-reported respiratory symptoms that are suggestive of a COVID-19 infection—having experienced both fever and shortness of breath in the past seven days. These controls had no effect on our original findings.

We further controlled for respondents’ self-reported respiratory symptoms that are suggestive of a COVID-19 infection—having experienced both fever and shortness of breath in the past seven days. These controls had no effect on our original findings.

As our normal lives are put on hold to try and flatten the curve of the deadly COVID-19 pandemic, some Americans are experiencing another kind of social injustice. Discrimination and unfair treatment are certainly nothing new to the racial and ethnic minority experience in America. One 2017 study and another in 2019 found that 25 to 49 percent of the population reported having experienced some form of unfair treatment or discrimination in their day-to-day life. The odds for non-Hispanic blacks to have such experiences ranged from two to five times higher than non-Hispanic whites, and the odds for Asians ranged from slightly less than non-Hispanic whites to three times higher than non-Hispanic whites.

What is striking in our findings is both that perceived discrimination in the United States persists, even during this global health crisis, and further, that a new form of discrimination and maltreatment resulting from fear of infection is rearing its ugly head and targeting both black Americans and Asian Americans at an alarming level. The reporting of any maltreatment due to perceived coronavirus infection is troubling in and of itself, regardless of one’s own racial or ethnic identification.

The targeting of African Americans appears to go hand-in-hand with longstanding maltreatment in America. References to the virus as a “Chinese virus” and a confluence of racialized rhetoric and finger pointing in America appears to have resulted in a novel form of discrimination that is disproportionately targeting Asian Americans. Our findings highlight the importance of dispelling targeted reactions towards racial and ethnic groups by eliminating racially charged and xenophobic rhetoric. The virus spreads through broad human practices that do not conform to borders or population sub-groups. It would benefit everyone to remember this fact.

If you or someone you know has experienced specific discriminatory acts, there are a number of resources available with more information and mechanisms for reporting incidents, including the Asian Pacific Policy and Planning Council.

Ying Liu, PhD, is a research scientist at USC’s Center for Economic and Social Research. She aims to better understand how we can improve health and education.

Brian Karl Finch, PhD, is research professor of sociology and spatial sciences at USC, senior social demographer at CESR, and director of the USC Population Research Center. He aims to understand the ways in which social context and genes interact to produce health disparities.

You must be logged in to post a comment.