Rosalie Liccardo Pacula and Adam Leventhal answer questions raised during “The Intersection of Two Pandemics: COVID-19 and Addiction” webinar.

On Thursday July 23, 2020, the USC Institute of Addiction Science and Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics co-hosted a webinar entitled, “The Intersection of Two Pandemics: Addiction and COVID-19.” The webinar focused on early evidence of how the COVID-19 pandemic was impacting those suffering from addiction. Preliminary drug overdose data for 2019 (prior to COVID-19) released by the CDC the week before the webinar showed that deaths from all drug overdoses, and opioids in particular, continued to rise, reaching historically new heights. Several stakeholders are concerned about whether policy responses to COVID-19 (requests to socially isolate, shut down of businesses, and reduced physical access to healthcare) will cause those suffering from addiction to fare even worse.

Below we answer important and timely questions from the audience on COVID-19 and addiction, policy issues, and data resources.

COVID-19 and Addiction

Q: What are the most immediate issues policymakers and providers are grappling with in regards to care for patients suffering from addiction during the COVID-19 pandemic?

A: Broader access to substance use disorder (SUD) treatment, not just opioid medication therapies, and supportive services that keep people in recovery are a major concern and both get destabilized by the pandemic as requirements to socially distance and the shutting down of non-essential businesses make it harder to deliver the treatment and supportive programing needed. Feelings of isolation and despair, coupled with lost employment and lost health insurance due to lost employment, are major concerns for those struggling with addiction, including those in recovery. How to address those issues directly, while effectively fighting the pandemic, is difficult and requires us to think of new ways to deliver services and help. ADM Giroir mentioned in his comments the need to provide “physical distance” rather than “social distance”, as the latter is in fact harmful and need not come with physical distancing.

Q: Both addiction and COVID-19 disproportionately affect racial/ethnic minorities. What state/federal policies can help these disadvantaged groups who may not always have access to care?

A: Great question! People tend to focus on access in terms of physical access (e.g. having a waivered doctor in the local geographic area). While that is a piece of it, I think it is a less important piece given very recent COVID-19 changes making access to telehealth more readily available which potentially opens the door for providers outside a patients’ geographic area. Medicaid and CMS have changed payment rules so that care received by outside of area providers via telehealth can be paid for through certain mediums.

A more important piece is the ability to pay for care, which is impacted by insurance. As such, one of the most important issues the federal government needs to address is growing uninsurance, which is only expected to get worse with the high rates of unemployment. We have to do something to make health insurance affordable and accessible, as healthcare costs without insurance are way too prohibitive even if it is physically close in proximity.

Furthermore, the data shows essential workers are disproportionately racial and ethnic minorities. Perhaps by the next pandemic (which I hope is never!), we will have disrupted social inequities such that minority groups are not unduly in jobs that could put them at higher health risk.

Q: Where do these issues with addiction and drug use fit in with our declining national life expectancy and why hasn’t the overall multiyear decline been considered a national emergency?

A: The decline in national life expectancy is in fact driven by rising rates of drug overdose deaths, including deaths from alcohol. So, the two are in fact the same thing, which is why we have such concern about rising use of substances and more relapse during COVID-19. For more about the role of drugs in life expectancy, see the Schaeffer Center discussion with Professors Anne Case and Angus Deaton.

Q: Is there evidence the national lock-downs resulting from COVID-19 disrupting illicit drug activity?

A: Unfortunately, no. Even in countries that have completely shut down their borders, experts studying the darknet activity suggests that black market has been highly innovative and active during the pandemic even though traditional drug trafficking routes have closed. New synthetic drugs, including fentanyl analogs, are being developed and local chemists keep coming up with new psychostimulants.

Treatment Programs and Policy Issues

Q: What do you see as the pharmacists’ role in terms of controlling prescription opioids use or misuse? Does it change with the COVID-19 pandemic?

A: Pharmacists can play a role in a number of ways, depending on the state laws. This includes (1) monitoring distribution of opioids to those having legitimate needs – paying close attention to escalation in amount / frequency and/or duration that might indicate potential misuse, and communicating with doctors when such issues are seen; (2) ensuring those with a prescription opioid are also being prescribed and/or provided naloxone, given risk of people misusing opioids at home; and (3) assisting patients with identification of safe pharmacy disposal so that unused prescription opioids do not sit at home (this might be especially important now while youth and others are sheltering in place).

Q: Over half of counties lack a Drug Addiction Treatment Act of 2000 waiver, which allows for prescribing or dispensing buprenorphine (an opioid use to treat opioid-use disorder as well as manage pain). Ironically, buprenorphine prescribed to treat pain does not require a separate waiver. Countries like Canada, France, and Switzerland do not have such restrictions on buprenorphine, and when France lifted restrictions on the prescribing of buprenorphine in the late 1990s, opioid overdoses fell 80%. A similar decrease in the U.S. would save more than 30,000 lives each year. How important is getting rid of the separate waiver requirement?

A: It is a very fair question and probably best answered by a clinical psychiatrist. Our colleague, Brad Stein, who is a clinical psychiatrist and leads the RAND-USC Schaeffer OPTIC center, explains that prescribing any potentially addictive drug – for pain or for addiction treatment – requires an understanding of addiction in general. It is important to note that addiction is a part of the basic medical training in several of the countries mention in the question, although it is not traditionally part of medical training in the U.S. unless a provider chooses to specialize in it. Hence Stein recommends policies that help overcome “healthcare deserts” by allowing for payment of distal providers and leveraging telehealth as a way of getting an appropriate specialist who does have a waiver administering these medications in a medically appropriate way.

We got into this opioid crisis through doctors prescribing medications with high addictive potential and lacking understanding and training to identify when use of the medicine was a problem. It seems like an easy lesson we can take forward, especially if we maintain policies recently implemented during COVID-19 that enable telehealth for addiction treatment.

Q: My biggest obstacle in my work as an emergency room social worker is not access to detox or inpatient/outpatient treatment, it is getting my patients to agree to treatment. Simply put, it’s not lack of resources in my area, it is lack of engagement. What programs could address this?

A: This is not an uncommon problem given that only 10% of the population that meet criteria for abuse and dependence have been to treatment (let alone stay in treatment). Substantial efforts have been undertaken to understand how we can get people to seek treatment, and recent pilots done at Yale Medical Center focused on opioid using patients suggest that buprenorphine induction during an ER visit is effective at getting the patient to actually go to treatment and/or stay with treatment. The problem is obviously much more difficult when the substance is methamphetamine where well studied medication therapies are not widely available.

Q: We have an understanding of the demographics and trends of addiction. The next step that is needed is to build a “recovery” or community-based model that addresses individual, family, and community recovery and health (population health), including harm reduction and increased access for veterans, etc. The literature is there. How do we get there?

A: You are right—there has been a lot of analysis done and a lot we know, but I can’t say that we have sufficiently identified what responses are right or how to integrate those responses into the healthcare system. The strongest support typically comes from outside the traditional healthcare system, but with monitoring by the system (e.g. housing support, employment opportunities, family reintegration, and so on). U.S. DHHS has not traditionally focused on these topics, as they tend to go broader than its mission.

Recovery is an ongoing process, like keeping up your exercise regime to keep diabetes or obesity under control. It takes external commitment devices and support groups, but often requires much more than what healthcare traditionally delivers (e.g. child care and/or income support to create time for this to happen; stable housing; and so on).

Q: What are your thoughts on decriminalizing drug use?

A: If by decriminalization you mean removal of the penalties for simple possession of drugs (no selling or intent to sale), then I would say in general I think that is a good approach for helping people suffering from many addictions, although I would note that most functioning decriminalized systems include penalties for individuals who drive impaired and/or distribute to minors.

If by decriminalization you mean the removal of restrictions on the sale of all drugs (which is in fact legalization, not decriminalization), I would suggest that we hold off on such a strategy. We don’t know how to sustain recovery for many people suffering with addiction (even alcohol, let alone illicit drugs). It seems wiser to figure out a successful strategy to support treatment addiction and recovery before a market is set up that is going to facilitate more people becoming addicted.

Additionally, decriminalization and commercialization often tend to co-occur but could be disaggregated. A key example is with cannabis. In legal cannabis markets, marketing and other factors that influence use among youth that were not seen before legalization are now abundant. Therefore, if commercialization is involved in decriminalization policies, regulation to prevent youth from accessing commercially-manufactured products and prevent companies from creating products that may be particularly appealing to youth (e.g., candy-related cannabis edibles) are needed to stem adverse impact on the pediatric health burden.

Q: Task forces and policing to remove illicit substances from communities seem to have political support. However, where does harm reduction programs and community support factor in to these strategies? Do you think there is political or state level support for harm reduction strategies? How do you see NIMBY (Not in my backyard)-ism playing into these issues?

A: Each community is different and has different needs and the relative importance of policing versus harm reduction will differ depending on the community characteristics and community needs. There is not one strategy that fits all. Furthermore, without community support for any approach, none will be successful. The science on the effectiveness of harm reduction programs is growing and generally showing positive results, particularly when police are facilitators in the harm reduction activities and/or in educating police about them. People may be shocked to know that there are policing groups actively engaged in educating police about these strategies.

Q: With so many addiction treatment centers allowing the use of tobacco, what are the efforts to include nicotine addiction treatment in substance use treatment? Especially now since both (smoked) tobacco and COVID-19 attack the lungs.

A: Interestingly enough, most private and public health insurers have been provided funding for tobacco addiction services even before federal laws mandated parity for addiction treatment services. We predict that as more and more treatment is provided within the traditional healthcare system, a greater focus will be paid to tobacco addiction as well as other addiction given the education of healthcare providers to reduce smoking in order to improve a variety of health conditions.

There was old clinical lore that if you do not allow people with non-nicotine substance use disorders (SUD) who are in treatment access to nicotine as a ‘substitute’ drug, they will be at risk to relapse back to their primary substance. There is now data debunking that hypothesis that shows, if anything, people who quit smoking during treatment for a non-nicotine SUD actually have better long-term SUD outcomes. With these data, it is hard to justify any reason why tobacco policies should be relaxed for SUD treatment clinics and centers.

Q: What steps are being taken to jointly address drug use and mental health issues, particularly depression and anxiety? What can be done to improve care?

A: We have a long way to go to jointly address drug use and mental health issues, but there is some progress being made in the following ways:

- Medicaid IMD exclusion waivers – which allow those with Medicaid insurance being treated for addiction to receive care in a traditional mental health facility. Previously such facilities would not be reimbursed for addiction care by Medicaid, which meant that people suffering from mental health and addiction would receive only care for one of their comorbidities. These waivers have become increasingly more common since 2015.

- Numerous efforts to improve integration of medical care and specialty services that were part of the Affordable Care Act, and provided temporary funding, block grant funding and alternative payment models to healthcare organizations if they did a better job integrating mental health and addiction services with physical health. These reforms include medical homes, accountable care organizations, and hub and spoke models that have been tried in various states and provided the opportunity for patients to be treated in a holistic and integrated way. Many of these experiments initially funded under the Affordable Care Act eventually got supported through private insurance initiatives.

There are also specialized psychotherapy programs designed to address both depression + SUD, which have shown some efficacy over standard SUD counseling. However, disseminating these programs has been a challenge because treatment providers on the ground cannot be expected to have expertise the variety of different treatment models and programs for each type of patient. An ongoing struggle between efficacy and reach.

Stimulant Misuse and Contamination, Poly-Drug Use, and Illegal Drug Use Trends

Q: Are deaths associated with stimulants a consequence of contamination of the stimulant with a potent opioid (eg, fentanyl) or is there thought to be another mechanism by which stimulants lead to overdose deaths?

A: Some of the problem could be contamination of the stimulant with fentanyl and other synthetic opioids. However, we are seeing self-reported use (through drug poison call data and treatment data, as well as some ethnographic data of drug users) showing that people are choosing to mix the two as well. So, what may have initially started as a “contamination problem” early in the black market, has evolved into a serious problem of poly-drug use by choice.

It also could be that people who use both stimulants and opioids might be more likely than opioid-only users to have medical comorbidities and social disadvantage that could leave them more vulnerable to overdose. A recent study shows that people who use opioid+meth vs. opioid only are more likely to have such characteristics that could put them at risk.

Q: If the stimulant problem is more so a polysubstance problem than stimulant epidemics of the past, to what extent do you think we can slow or foreclose the spread of polysubstance/methamphetamine addiction by aggressively treating existing cases of opioid addiction?

A: If our treatment facilities are focused on addiction treatment overall, then some of the factors influencing polysubstance use will be addressed. If our facilities are just prescribing buprenorphine for opioid addiction and not providing behavioral therapy to address the use of other substances, then it is missing an opportunity to really treat/heal the individual and is falling short. Unfortunately, there are no FDA-approved pharmacotherapies for stimulant use disorder, making use of behavioral interventions and community and national policies particularly important for addressing people with this illness.

Q: Which is the current status of bath salts and khat problems?

A: Bath salts and khat remain more of a local regionalized problem in a few parts of the U.S., and not something that has grown popular outside of a few markets. They provide yet another example of why addiction needs to be tackled on a community-by-community basis.

Q: Is there any indication that illicit drug dealers are seeing the business logic of replacing cocaine with methamphetamine in the way that they saw the logic of replacing heroin with fentanyl? In both cases the latter are industrial rather than agricultural, more profitable, and more potent. But also much more deadly.

A: Illicit drug dealers are nothing if not innovative and efficient. Fentanyl emerged as a filler for heroin, and when some users realized it was actually more potent and effective, they actual switched (after getting experience). It is possible that methamphetamine or other synthetic stimulants may be able to replace some of the cocaine market, although I would be surprised if it is all of the market, given the very negative impacts many of these synthetic stimulants have on the body. Cocaine users don’t suffer from meth mouth and skin lesions for example.

Data and Resources

Q: The substance use data in my state has not been updated since before the pandemic (capacity is limited). What are some other community indicators I can look at to supplement the national data trends?

A: There are at least two resources you might draw on: (1) local community hospitals should be able to provide data on drug-involved ED visits and/or admissions, as hospitals track admissions data in real time; (2) drug-involved poison calls (which may or may not generate a hospitalization). In addition, some communities track waste water and local treatment admissions, but that varies by community.

Q: How would the panel recommend that we integrate COVID-19 assessment into our ongoing addictions research projects? Are there certain surveys, assessments, or questions that you view as sound pandemic-related instruments or as important pandemic-related data that should be collected?

A: There are a few assessments being developed, but none have been tested sufficiently to warrant a strong recommendation. Check out the NIH COVID-19 Research Tools page for resources.

Q: What resources are available to researchers wanting to learn more about opioid addiction?

A: The RAND-USC Schaeffer Opioid Policy Tools and Information Center as well as the USC Institute for Addiction Science.

Q: Is there any data on cannabis use trends? Is there evidence trends are changing during COVID-19?

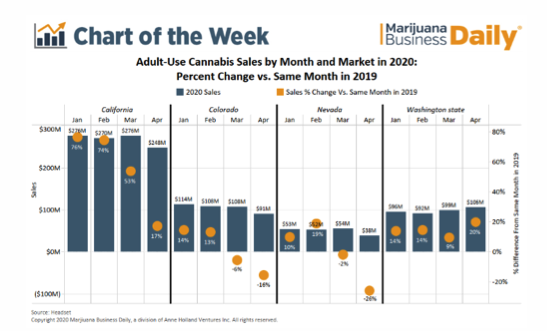

A: There is some evidence of rising cannabis use during COVID-19 (there are preliminary studies looking at this issue at the Research Society on Marijuana Conference.) The best data really comes from the cannabis industry, which suggests that sales are up even during lock down months in some states (CA, WA, AZ, MI and IL)– although not all (CO and NV show declines). Below is a slide from the MJBizdaily news on a few of those states:

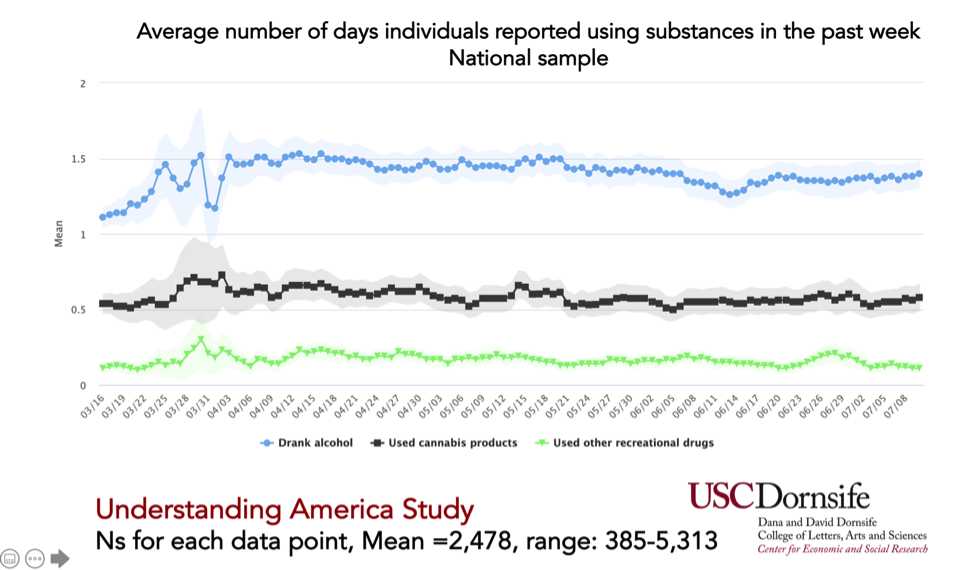

A survey study conducted by USC that is nationally representative does not show much change in the number of days used cannabis over the past few months:

Q: Is there any data on substance use prevalence in young adults (18-24) after the stay at home order? Does it vary greatly by substance?

A: There will be in a few months.

Q: Are there ways to differentiate between powder cocaine and crack in the data?

A: In mortality data, no. In self-reported data or lab seizure data, yes.

You must be logged in to post a comment.