Understanding what the U.S. population thinks about our education system is critical to supporting children. Students lost years of learning during COVID school disruptions, and academic progress post-COVID is still sluggish. Nationally, unacceptably high rates of absenteeism are nearly double pre-pandemic levels. And today’s youth are suffering at unprecedented levels in terms of poor mental health, with increased rates of suicide, anxiety, and depression.

Adults’ beliefs about education matter, as votes determine local, state, and federal elections as well as the development and passage of legislation. Moreover, parents’ understanding of their child’s needs inform whether they seek or sign up for available student services, interventions, and supports.

What do adults know about U.S. education and where do they get their information? We addressed these questions in “What do adults know about education?” (Phi Delta Kappan, September 2024). We surveyed over 1,600 households with school-age children and over 2,000 without school-age children through the Understanding America Study, a nationally-representative panel of households in the US.

Here we summarize a few findings from this report.

Almost half of adults don’t know what is and isn’t taught in schools.

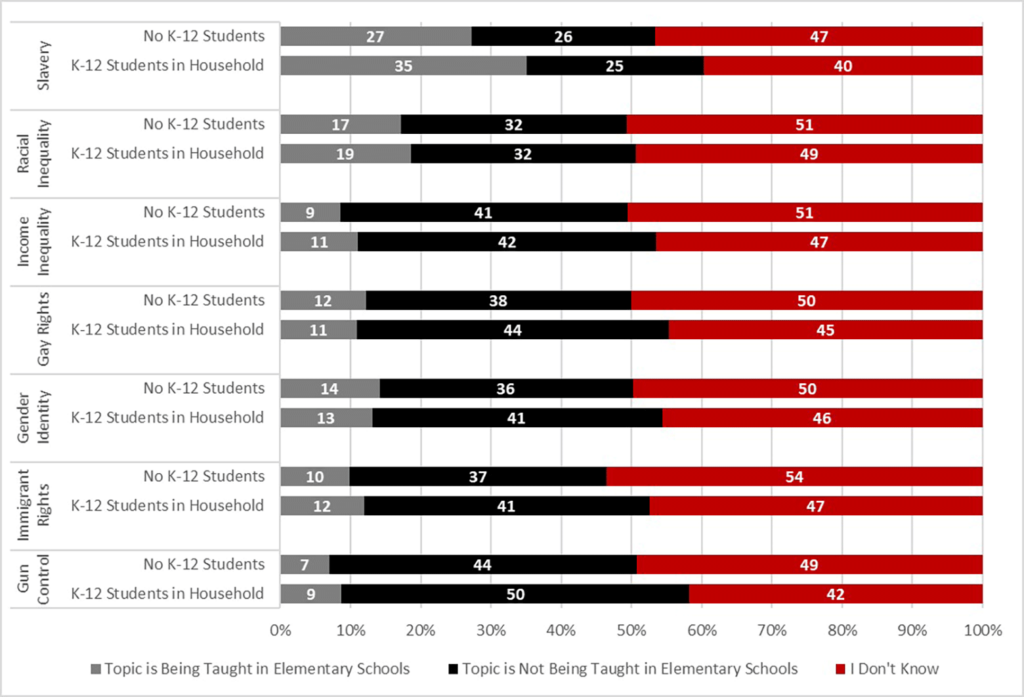

We asked respondents whether a series of topics spanning civics, race, history, LGBTQ issues, and sex education were currently being taught in schools across the country (Polikoff et all, 2022). On every item we asked about, almost half of our sample (46% on average) answered “I don’t know”. Remarkably, results were no better among households with children currently in schools (the bottom bar in each pair).

Sample items showing high rates of not knowing whether a topic is taught in elementary schools

Americans are unsure who influences what is taught in classrooms

We asked adults to rank six different groups (parents, local school boards, teachers, school and district leaders, state leaders, and national leaders) in the order in which that group influences what is taught in public schools. With each group receiving the top rank from approximately 10-20% of respondents, there was no consensus or agreement on who does have the most control. In other words, respondents were equally likely to attribute the most control to school boards, national leaders, teachers, etc. Responses from households with school-aged children showed the same pattern.

Americans admit not understanding issues that do influence school policy

One might expect adults to have strong opinions or beliefs about the role of privatization in education, especially whether federal dollars should be spent improving public education or increasing competition by supporting private school payments (e.g., through vouchers or federally supported education savings programs).

We presented a series of questions about potential benefits and downsides of privatization, seeking to tap into adults’ belief systems that might underly their positions on public versus private education spending (Saavedra, et al. 2024).

Approximately one in five respondents answered “I don’t know” to many of the statements (18% – 24% variation across items), conveying lack of positioning on one or the other side of these important beliefs about education. The same was true for households with and without K-12 students (21% and 19%, on average across the items respectively).

Americans’ perceptions of student progress don’t align with experts’ analyses of hard data

We have also shown a consistent pattern of misalignment between what parents think and what expert analyses and assessments have concluded. Among our nationally representative sample of households, children likely have academic experiences mirroring national trends. But what we hear from the adults do not track along with these trends.

- Despite unprecedented learning losses in recent years

(Kane and Reardon, 2023) our sample of households with K-12 children have expressed decreasing levels of concern about their children’s academics since 2021, and that concern has stayed low ever since (Silver et al., manuscript under review).

Academic concerns over time

- Although state and national data show almost 30% of students were chronically absent in 2021-22 (only slightly less in 2022-23) only five percent of surveyed households reported absence rates that high (i.e., missing 10% or more of school’s instructional days).

- Among those parents whose children were on pace to be chronically absent, less than half expressed concern about it (47%). Experts, on the other hand, refer to chronic absenteeism as a “crisis” (Hess & Malkus, 2024).

Prevalence of absences, and concern about level of absenteeism

| Number of days missed during first half of 2022-23 | Percent of sample | Percent concerned or very concerned about absences |

|---|---|---|

| Five or fewer | 85% | 5% |

| 5 – 10 | 11% | 29% |

| 10 or more (on pace to be “chronically absent” by end of year | 4% | 47% |

Adults mainly learn about education issues from “personal experience” – not from news sources

We were surprised to find that “your own personal experiences” was the only source of information that a majority of respondents acknowledged as a “major influence” on their views about educational topics (Table 1). No other source of information was reported by more than one-third of respondents as a major influence. Even more surprising, less than one-third of households with a K-12 child in the home reported that “communication from local schools” is a major influence on their views and beliefs about the school curriculum!

Table 1. “Major” influences on adults’ views about what is, and should, be taught in schools.

| Major influences | Overall | K-12 child in home | No k-12 child in home |

|---|---|---|---|

| Your own personal experiences in schools | 58% | 62% | 54% |

| Television/cable news | 32% | 29% | 35% |

| Social media | 29% | 33% | 26% |

| Friends, family, word of mouth | 29% | 30% | 29% |

| Communication from local schools | 27% | 32% | 22% |

| Books | 24% | 23% | 26% |

| Newspapers | 15% | 14% | 16% |

| Podcasts | 14% | 14% | 14% |

Where do we go from here?

Information is powerful.

We’ve twice shown that it can be quite easy to move people’s opinions and intentions about school-related issues simply by providing additional information. In one demonstration, we presented respondents with a hypothetical situation in which a parent wants to opt a child out of a history lesson “that contains content they disagree with.”

In the absence of additional information, 57% believed that the teacher should honor the parent’s request (Saavedra et al., 2024). A random half of the sample saw a few additional sentences – that children learning about content they might not otherwise hear or learn about helps them to learn new perspectives and to think critically, and that it can be hard for a teacher to accommodate every parent’s wish for every lesson for every child. Among those receiving the few additional sentences, 41% believed that the teacher should honor the parent request – a sixteen percentage point (nearly 30%) reduction in supporting parent opt-out.

We must improve communication from and about schools

Improving communication is critical to the future of public education, which is itself critical to healthy democracy. Parents and non-parents must be part of the conversation. Schools must provide information and data that is representative of the curriculum schools are using and children’s’ progress. Messaging must be clear and informative.

The same norms for productive discussion we seek to develop in children also apply to adults, including educators and parents.

The responsibility does not lie solely with parents or solely with schools. To improve our public education system, reduce academic achievement gaps, recover from COVID learning losses, and prepare students for a productive life after compulsory education, we need an educated voting public. Greater knowledge and awareness of what is happening inside our school buildings is key to this understanding.

References

Hess, F.M. & Malkus N. (February, 2024) Chronic absenteeism could be the biggest problem facing schools right now. The American Enterprise Institute. https://www.aei.org/op-eds/chronic-absenteeism-could-be-the-biggest-problem-facing-schools-right-now/

Kane T. and Reardon S., (May 2023). Parents Don’t Understand How Far Behind Their Kids Are in School. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2023/05/11/opinion/pandemic-learning-losses-steep-but-not-permanent.html

Polikoff, M., Silver, D., Rapaport, A., Saavedra, A., & Garland, M. (2022, October). A House divided? What Americans really think about controversial topics in schools. University of Southern California. https://tinyurl.com/HouseDividedReport

Saavedra, A.R., Polikoff, M. & Silver, D. (2024). Parents are not fully aware of, or concerned about, their children’s school attendance. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/articles/parents-are-not-fully-aware-of-or-concerned-about-their-childrens-school-attendance/

Saavedra, A.R., Polikoff, M., Silver, D., Rapaport, A., Garland, M., & Scollan-Rowley, J. (2024, February). Searching for Common Ground: Widespread Support for Public Schools but Substantial Partisan Divides About Teaching Potentially Contested Topics. University of Southern California. https://bit.ly/3wgszlD

Silver, D., Polikoff, M., Garland, M., Rapaport, A., Saavedra, A., & Fienberg, M. (under review). The evolution of caregiver concerns, child wellbeing, and availability of school-based recovery interventions during the Covid-19 pandemic. AERA Open.

You must be logged in to post a comment.