Editor’s note: This op-ed was first published on LinkedIn on February 1, 2022.

Biomedical innovation—and Alzheimer’s patients–took a deep dagger in early January when Medicare proposed drastically limiting coverage of Aduhelm, the first Alzheimer’s drug to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) since 2003.

The proposal, which could become final in April after a public comment period, ducked the key policy challenge, which is to design reimbursement schemes to encourage valuable innovation while controlling costs.

Historically, the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) has not taken costs into account as it plans for coverage of FDA-approved drugs. It claimed to follow that precedent in this case. But costs clearly mattered.

Biogen, the maker of Aduhelm, projected only 50,000 people might take the drug in the first year, at a cost of about $56,000 each. The total would have amounted to about $3 billion, a fraction of one percent of Medicare’s total budget. But critics of the drug had their eye on the millions of Americans who might ultimately seek treatment. As the CMS panel met to make a national coverage decision on Adulhelm, Medicare boosted Part B premiums to build a reserve in case the drug got a green light. When Biogen cut the list price in half to roughly $28,000 in December, Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra took the highly unusual step of ordering Medicare actuaries to recalculate premiums.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

In the end, CMS opted for a cheap solution. It advocated that coverage be extended only to individuals enrolled in a new series of clinical trials. It said it was concerned about safety, but that is illusory. The FDA, which is responsible for safety evaluation, had already looked at the data and approved the drug.

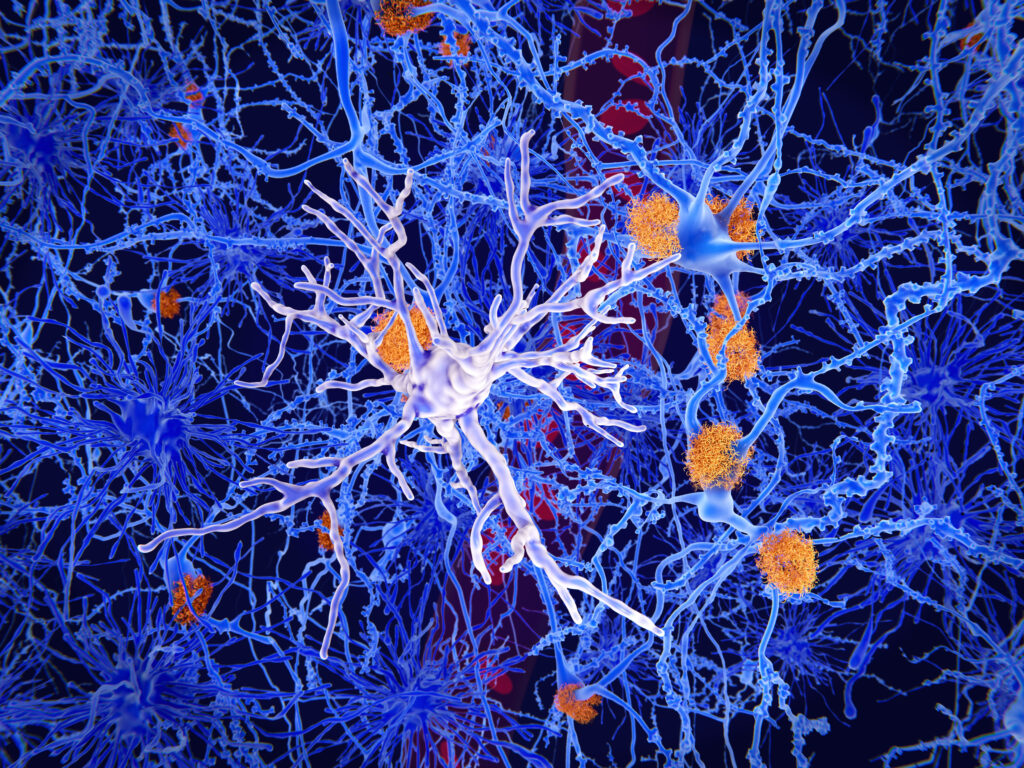

The CMS proposal is a failure of will and of imagination. As shown in previous clinical trials examined by the FDA, Aduhelm reduced amyloid plaques and neurofibrillary tangles in the brain. These are key pathological hallmarks of the disease, which has contributed to the deaths of as many as 1 million Americans over the last decade. Six million Americans are currently living with Alzheimer’s, which is expected to rise to 13 million by 2050. CMS punted the ball with our team down 14 points late in the fourth quarter.

If costs are to be considered, then CMS could break the mold and start tying drug reimbursement to meaningful patient outcomes, much as it has done with hospital services. Once safety and function are established by FDA review, value is best established by seeing how new treatments diffuse into clinical practice.

In the case of Aduhelm, a deal could have been struck to keep prices low while the drug is proving its value. Metrics could include results from imaging studies measuring plaque accumulation or cognitive batteries administered and reported by physicians. If the drug is delaying progression of the disease, and saving the nation billions in medical and caregiving costs, then Biogen should be rewarded for its innovation. If the drug proves ineffective, then usage, coverage and prices will naturally fall. In this way, patients could gain access years earlier without breaking the bank, but with a promise from Medicare to pay more once the manufacturer demonstrates true effectiveness. (Disclosure: Goldman is an economic advisor to Biogen, including advising on Aduhelm. Biogen was not involved in the development of this article).

Critics point out that of the two clinical trials run by Biogen, only one showed a slowing in disease progression. But the FDA noted that the patients in the second trial received less treatment, and granted Aduhelm accelerated approval rather than waiting for results from another large, time-consuming trial in which half the patients are given a placebo. The FDA idea, thwarted by CMS, was to allow access to a promising drug and use real world data to learn how patients who truly are suffering respond. The evidence gathered from real-world use often proves invaluable. For example, it took several years in the market before cholesterol-reducing statins were proved to show a reduction in deaths from heart disease. Scientists suspected that would happen, but it took time to show the connection, and in the meantime many lives were saved.

While waiting for the CMS decision, many hospital systems opted not to prescribe Aduhelm. Now, if coverage is ultimately denied, that picture will change only for the worse. Even with its proven capabilities, the drug will remain under a cloud for years until Biogen can complete another clinical trial. Meanwhile suffering will mount.

There is still time for CMS to reverse field and issue a final determination that rewards innovation and keeps hope alive for millions of people who are trying to avoid one of the nation’s most brutal, impoverishing diseases.

Dana P. Goldman is Dean of the USC Price School of Public Policy and co-director of the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. Joseph Grogan is a nonresident senior fellow at the Schaeffer Center and former Director of the Domestic Policy Council for President Donald Trump.