Big data tell many of today’s stories in research news, but our recent study underscores the need for caution when reporting the rate of childhood obesity. A Centers for Disease Control and Prevention health survey last year showed that the overall rate of childhood obesity plateaued, but a more granular set of data by the National Center for Education Statistics indicated that only children in wealthy households are trimmer.

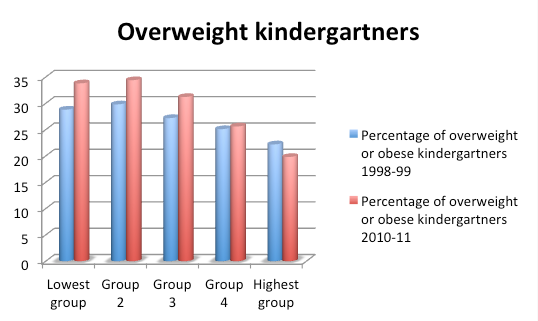

My colleague Paul Chung from UCLA and I analyzed the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study and found overweight and obesity increased 20 percent among kindergartners from low- and middle-income households over the course of a decade, from 11.6 percent in the 1998-99 school year, to 13.9 percent in 2009-2010. This shows that kids from these backgrounds are still entering school with a significant obesity problem.

At the same time, our study showed the obesity rate of kindergartners from the wealthiest households fell 2.4 percentage points from 1999 to 2010, from 22.2 percent to 19.8 percent. The decline in obesity among wealthy children may explain the plateau in the CDC survey’s overall rate.

The differences in study results are a reminder that a study sample’s size and representation can greatly influence scientific outcomes and conclusions. While the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study involved more than 15,000 kindergartners, the CDC survey involved a smaller group – 5,000 participants – who ranged in age from birth to adult. These findings suggest that the news of overall static trends must be interpreted cautiously and underscore the need for understanding the drivers of these socioeconomic differences.

Our findings were published in a research letter for June’s JAMA Pediatrics, which can be found here.