In the 1980’s movie, “The Gods Must Be Crazy”, a group of African tribesmen living in the Kalahari Desert are confounded by a bottle of Coca-Cola they find that has been dropped from an airplane into their isolated enclave. The villagers quickly move from curiosity to confusion to anger as they attempt to understand this strange object and ultimately their leaders decide that it must be removed.

This has been approximately the same reaction that the release of our USC Dornsife/LA Times “Daybreak” presidential poll has caused in the mainstream political community since its initial release last month. Those of us involved with the poll have attempted to explain through interviews, op-eds and news releases that the Daybreak poll measures a different component of public opinion than traditional polls: its goal is to determine not only voter preferences in the 2016 presidential race but the intensity of those preferences by asking respondents not only to indicate which candidate they are likely to vote for but how committed (on a scale of 1-100) they are to support that candidate.

Very few voters shift their support on an absolute basis – from total and complete certainty for one candidate to equally unequivocal certainty for the other. Most people change their minds on most matters much more gradually. So an attempt to assess more ongoing changes in voter sentiment seems like a reasonable way to augment a traditional all-or-nothing survey, especially given the difficulties that the traditional approach has faced in so many recent elections both in this country and internationally.

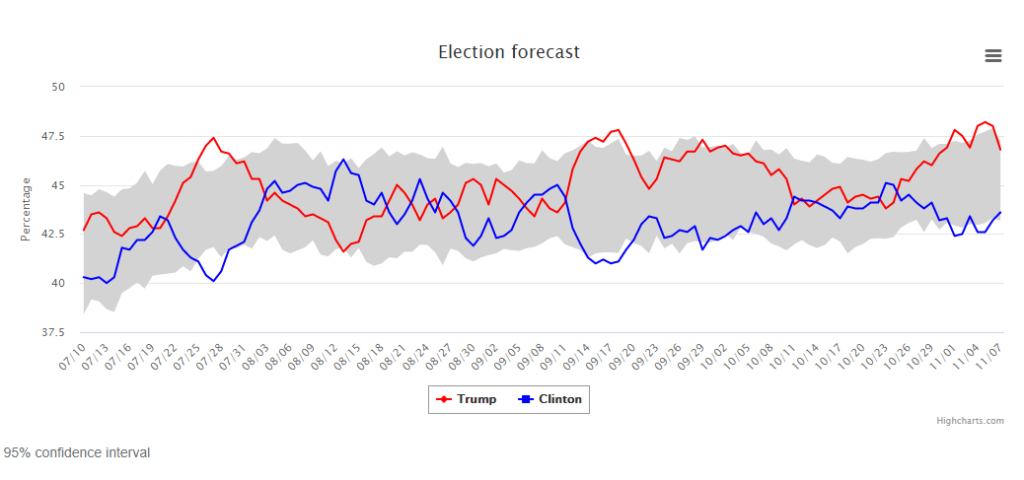

Like most traditional polls, the Daybreak poll has shown that Hillary Clinton’s support has grown at the expense of Donald Trump’s over the last several weeks. But the Daybreak poll has also consistently shown Trump with a higher level of support over that time span than has been the case in polls that only measure voter preference without attempting to gauge intensity.

This has the potential to open the door to a fascinating body of research. If Trump voters are smaller in number but stronger in the intensity of their support than Clinton’s, this raises a series of critical strategic questions related to campaign messaging, grassroots organizing, and the role of paid vs news media. It suggests a new approach to measuring shifts in voter opinion as well as a clearer understanding of how such decisions are made.

But none of those conversations are taking place. Rather than exploring the possibilities that this new complementary approach presents to the political conversation, the overriding reaction from the mainstream political commentariat has been one of criticism and derision. To be sure, a significant portion of this response is due to the extreme emotions that Trump’s candidacy provokes among most Americans. Given that his demographic base of support is with voters who lack a college education, it’s statistically unlikely that most political scientists, journalists and other commentators are fans of Trump. While the ethics and customs of these professions tend to discourage outright advocacy for a candidate, there are no such restrictions on venting equally strong emotions about a public opinion poll that produces results significantly different than others.

Is the vitriol being directed at the Daybreak poll a stand-in for the type of sentiments that our critics would prefer to be directing at Trump himself? When a McClatchy poll showed Clinton with an unusually large fifteen point lead a few weeks ago, most of those who have criticized the Daybreak poll with such vehemence responded with a curious murmur at best. It’s reasonable to assume that results like ours appearing during a Romney-Obama or Bush-Gore contest (or a Clinton-Rubio campaign) would engender more curiosity than outrage.

But just as much of this hostility is likely to be simply an innate skepticism toward the unfamiliar. The Daybreak poll’s 2012 predecessor was extremely accurate in calling the outcome of that year’s campaign, which makes it plausible that it can be just as successful this year. But it would be presumptuous to come to that conclusion in August rather than waiting until November. Perhaps the more appropriate response to new and unfamiliar information is to study it and learn from it, before either accepting or dismissing it prematurely.

It is entirely possible that the strongly negative feelings voters harbor toward both Trump and Clinton this year could be creating unforeseen challenges with this approach. But it is also possible that, just as George Gallup decided several decades ago that it was smarter to knock on voters’ doors rather than to simply question them in the town square, maybe a less traditional and more innovative approach to public opinion research can be a more effective one.