Editor’s Note: This analysis is part of the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, which is a partnership between Economic Studies at Brookings and the University of Southern California Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings. This post originally appeared in Health Affairs on September 10, 2019.

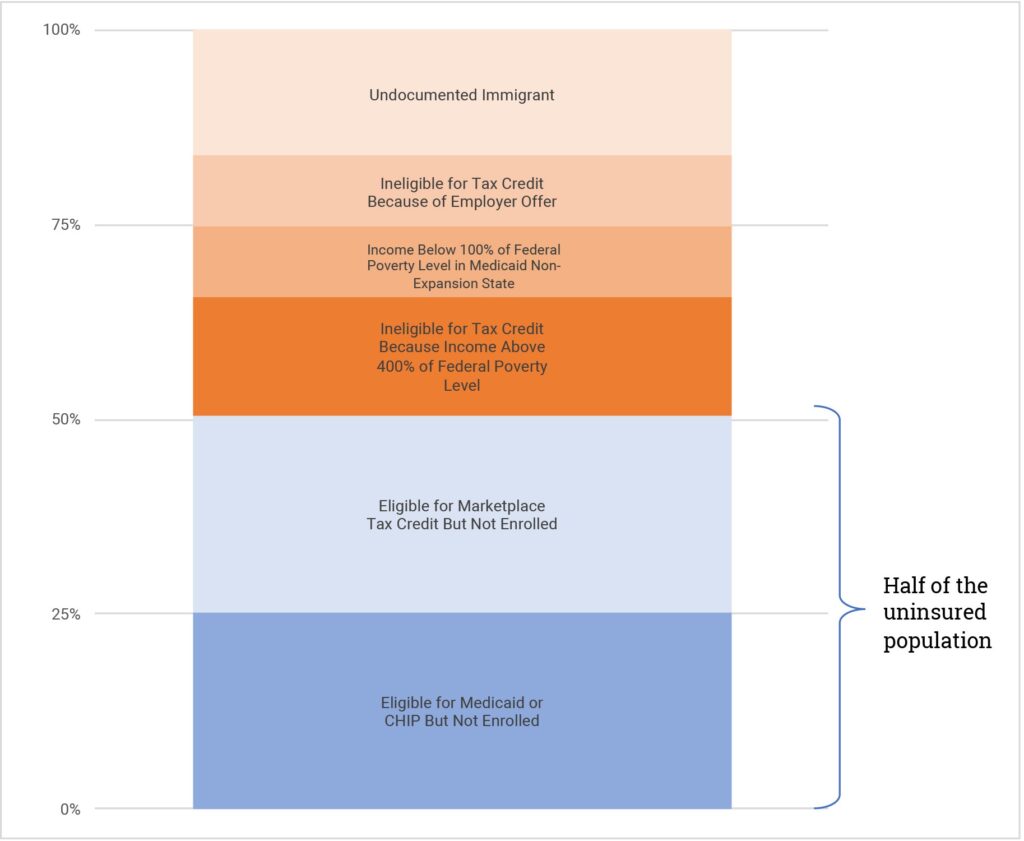

Over the past decade, the Affordable Care Act (ACA) has dramatically increased the share of Americans with health insurance coverage, but 30 million people remain uninsured. As shown in Exhibit 1, millions of people are uninsured because the patchwork of current policy leaves them ineligible for coverage assistance. At the same time, fully half of the uninsured are eligible for coverage through Medicaid or are eligible to receive financial assistance to buy coverage in the health insurance Marketplace.

That means that helping people benefit from the programs for which they are eligible could have a significant impact on the share of Americans with health coverage, making the idea of automatic enrollment into coverage attractive across the political spectrum. This post explores a “retroactive” approach to automatic enrollment in private health insurance, and it describes analogous features in other social programs to illustrate why a retroactive approach would be politically feasible.

Exhibit 1

Source: Blumberg LJ, Holahan J, Karpman M, Elmendorf C. Characteristics of the remaining uninsured: an update, Washington (DC): Urban Institute; 2018 Jul 11.

What is “Retroactive” Enrollment?

Typically, when we think about enrollment into public health insurance programs, we imagine individuals providing information, receiving an eligibility determination, and then enrolling in (and, where applicable, paying premiums for) coverage that will pay for health care services they receive going forward. This generally requires the active, prospective involvement of the enrollee, since there is no other mechanism for obtaining the necessary information and no way to collect premiums without the individual’s involvement. A retroactive approach is different. Individuals who are otherwise uninsured can be considered covered by an insurance product that will pay claims for any health care services they receive. Then, at some future point, their eligibility can be assessed and retroactively accounted for and any applicable premium can be collected. Under this approach, individuals have the benefits of health insurance—access to the health care system and financial protection in the event of serious illness—during the period they would otherwise have been uninsured. And those benefits can be provided without the individual taking any prospective action.

The Example of Medicaid’s Retroactive Coverage Period

A retroactive approach to enrollment may at first seem unusual, but it is a feature of today’s health policy landscape, specifically in Medicaid. When an individual becomes newly enrolled in Medicaid, the program generally provides coverage for medical services received in the three months prior to the time they submitted their application for Medicaid coverage. That means that if a Medicaid-eligible individual presents at a health care provider in need of care, the provider can deliver services while working to get the individual enrolled in Medicaid coverage and then be paid for those services through the retroactive coverage period.

This is an important aspect of Medicaid that accounts for a significant portion of program spending. According to one (pre-ACA) estimate, about 5 percent of Medicaid spending occurs during the retroactive coverage period. Similarly, a 2016 analysis of one state’s data by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services indicates that about 14 percent of beneficiaries have claims during the retroactive coverage period averaging $1,561 per person. In states and eligibility groups where Medicaid benefits are provided by managed care organizations, retroactive coverage is generally handled outside the managed care system, with the state paying claims on a fee-for-service basis.

As a result, individuals who are eligible for Medicaid with retroactive coverage have a significant amount of insurance protection even when not enrolled. They are mostly insulated from financial exposure in the event of a major medical event, and they generally can access care if they become sick. Certainly, there are significant individual benefits of affirmatively enrolling, including better access to primary care and reduced worry about potential medical bills. Enrollment also facilitates care coordination and care management supports that can lead to higher quality and lower costs. Nonetheless, because of the retroactive coverage period, the Medicaid-eligible “uninsured” still have a meaningful amount of insurance, even without an insurance card.

Bringing Retroactive Enrollment to the Individual Market

This same principle could be adapted to the individual market, but with important modifications. The most significant issue is adverse selection: A retroactive approach to enrollment allows individuals to, almost by definition, wait until they become sick before “signing up” for coverage. This is not a problem in Medicaid since individuals owe, at most, only nominal premiums that are not a meaningful source of program financing. But to make retroactive enrollment work in the individual market, we need a strategy to ensure individuals are contributing to the cost of coverage even when healthy. Put another way, since retroactive enrollment ensures that people have the financial protection of insurance even if they have not yet enrolled, it should ensure that people are contributing toward the cost of that benefit.

As outlined elsewhere, one approach would be to create a “backstop plan” that would provide coverage to the otherwise uninsured. Everyone who is uninsured and not Medicaid-eligible would be considered covered by the backstop, with no action required. When people file their taxes each year, they would pay an income-adjusted premium for the months they were covered by the backstop, equivalent to the income-adjusted premium they would have paid to obtain low-cost insurance if they had affirmatively enrolled in the individual market. Notably, this approach would function most effectively if financial assistance for individual market coverage were made more generous than it is today, so that the premiums for the backstop plan and for affirmative enrollment were lower than under current law.

This backstop plan premium would be paid regardless of whether or not the individual accessed any health care through the backstop. The backstop plan would be considered a part of the individual market risk pool and would participate in risk adjustment.

When backstop-covered individuals need medical care, the backstop would function like any other insurance plan, paying claims and providing utilization management and care coordination. Cost sharing would be structured as a catastrophic plan design, with all treatment except high-value services and preventive care subject to a deductible, which could be income-adjusted.

Because the backstop would cover people who have not made any affirmative decisions about their health coverage, it would need a mechanism to establish a payment amount for services received from any provider where a backstop-covered individual seeks care. This could include requiring providers to accept a specific out-of-network rate, at least for emergency services or potentially for the full suite of health benefits. In this respect, the backstop plan would function much like a public option and could be operated in conjunction with a new public plan in the individual market. One could also imagine limiting the backstop to covering claims for only a short period, such as 30 days, after which the individual would be required to affirmatively select (or be assigned to) a “traditional” individual market plan.

Other Public Benefits Include Features Similar to the Backstop Plan

Some may argue that retroactive enrollment through a backstop plan would be simply a rebranding of the ACA’s individual mandate and thus would share the mandate’s political toxicity. And this approach does have some similarities to the ACA’s mandate: It would be operated through the tax system as a tool to bolster the sustainability of a community-rated risk pool.

But better analogies than the individual mandate can be found outside the combative politics of health care. In important respects, the backstop plan is similar to programs such as unemployment insurance and the workers’ compensation system. In those cases, policy makers have determined that workers should have a specific insurance benefit, so the entire covered population is charged a “premium” for the coverage. Notably, in both programs contributions toward workers’ coverage are made automatically (through employer-side payroll taxes for unemployment insurance and premiums paid by employers for workers’ compensation) and workers go through a formal enrollment at the time they need to access benefits—in much the same way that the backstop plan would collect premiums through the tax filing process and enroll people at the time they access health care services.

There are certainly difference between these examples and retroactive enrollment into a backstop health insurance plan. Health insurance is a far costlier benefit, and unlike the very broad base for unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation, the backstop plan would cover only the narrow segment of people who were otherwise uninsured. Retroactive health insurance enrollment as laid out here would also feature direct, individual-level competition between private plans and the backstop option, which is not a feature of the other benefits. Nonetheless, just as the example of Medicaid’s retroactive coverage period demonstrates that our current health care system could accommodate the backstop plan approach, the existence of unemployment insurance and workers’ compensation make clear that this approach is politically viable.

Indeed, retroactive enrollment into backstop coverage could channel many of the political impulses that are animating the conversation about next steps in health reform. Perhaps most importantly, the backstop plan represents a path to truly universal coverage that would not directly disrupt existing coverage options. Given our current patchwork of coverage sources, the population of uninsured is ever changing: An analysis of 2012 data showed that 5 percent of the uninsured had coverage just one month prior, and 20 percent had coverage five months prior. No system that relies on a discrete action to “start” enrollment can keep up with this degree of churn and provide universality.

Retroactive enrollment into the backstop would addresses this problem. At the same time, a retroactive approach could speak to industry opposition to a public option. Specifically, while the backstop might introduce a form of public option, it would also bring a large pool of relatively healthy individuals into the risk pool and dramatically reduce health care providers’ uncompensated care burdens, which could be an attractive trade-off for providers, insurers, and other stakeholders.

You must be logged in to post a comment.