It’s easy to get distracted by the controversy and politicizing that all-too-often occupies vaccine debate, but regardless of one’s stance on the issue, the high costs associated with the diseases they prevent are indisputable.

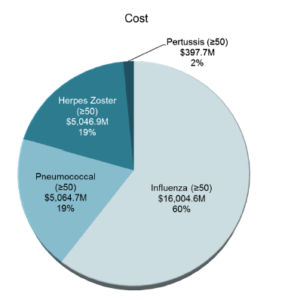

In a study my colleagues and I found the annual economic burden of four vaccine-preventable diseases (influenza, pneumococcal, herpes zoster(shingles), pertussis(whooping cough)) to be an estimated $26.5 billion among adults aged 50 years and older in the United States.

Of the $26.5 billion, 73 percent was attributed to medical costs while the remaining 27% represent indirect costs such as work and productivity loss due to disease. Neither mortality costs nor leisure time costs due to disease are captured in our estimate. Had they been, the economic burden would be even greater. Of the four diseases included in the analysis, influenza and pneumococcal accounted for nearly 80% of the total costs. More specifically, influenza was found to have an estimated annual cost of $16 billion, and pneumococcal $5.1 billion.

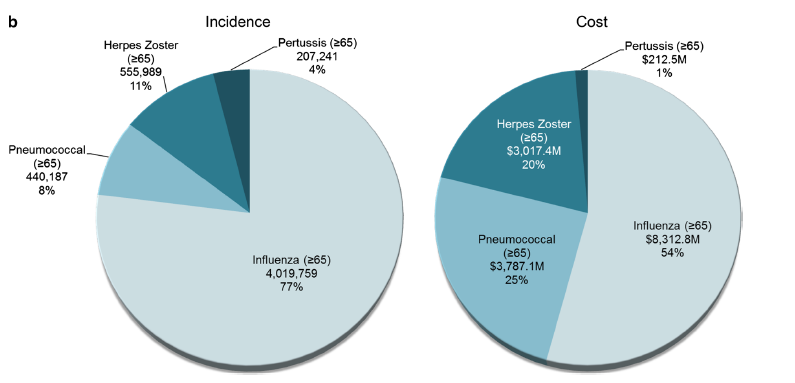

In a subset analysis of adults 65 and older, we found that although pneumococcal disease represented only 8 percent of total cases, it contributed to one-fourth of the total costs. A similar pattern emerged with shingles, which made up 11% of total cases but 20% of total costs among adults 65 and older.

Potentially driving the high collective costs to society of these diseases is low uptake of currently recommended vaccines. Although the CDC makes specific influenza and pneumococcal vaccine recommendations for adults, recent reports have indicated that less than 50 percent of adults received an influenza vaccine in 2014, and only 60 percent of adults 65 years and older have ever received a pneumococcal vaccine. Furthermore, pneumococcal vaccine uptake is particularly low in certain subpopulations, for example it is only 48 percent within the black population and mere 39 percent among Hispanics.

Given the substantial costs of vaccine preventable diseases, improving adult immunization rates should be a public health priority moving forward. Research has suggested that barriers to vaccination exist at the patient, provider, and system level. Therefore, it is critical to prioritize, evaluate, and continuously improve adult immunization efforts across all three of the levels. Previous studies have suggested that the implementation of standing orders for vaccination, assigning non-physician personnel vaccination responsibilities, and in-person clinician recommendation have the greatest impact on increasing uptake. Implementing these types of policy efforts in sub-populations most at risk for developing adult vaccine-preventable disease and at greatest risk for not being vaccinated is a good starting point and will likely yield the greatest benefit.

You must be logged in to post a comment.