Across the country states are grappling with growing populations with infectious disease, many of which disproportionately affect vulnerable populations who have the least access to care.

Hepatitis C is a particularly egregious example. Twenty-thousand people die from hepatitis C each year; that is more than the combined death toll from 60 other infectious diseases (including HIV) combined. And unlike other public health challenges, there is a cure that has been on the market since 2013.

This duality – a cure for a devastating disease and limited access to it due to a high price tag – were what motivated Neeraj Sood, a professor at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics and the Price School of Public Policy, to explore innovative payment models as a strategy for government entities to be able to pay for lifesaving cures that could eradicate diseases like hepatitis C.

Sood participated on a National Academies of Sciences Committee which published two reports focused on strategies to eliminate hepatitis B and C in the United States. The committee found that if 85 to 95 percent of the people with hepatitis C were treated, the disease would be eliminated as a public health problem. But paying for the curative treatment has stymied uptake among those infected and created a barrier to eliminating the disease, Sood noted at a July 22, 2019, event hosted by the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy and the Brookings Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy.

Sood participated on a National Academies of Sciences Committee which published two reports focused on strategies to eliminate hepatitis B and C in the United States. The committee found that if 85 to 95 percent of the people with hepatitis C were treated, the disease would be eliminated as a public health problem. But paying for the curative treatment has stymied uptake among those infected and created a barrier to eliminating the disease, Sood noted at a July 22, 2019, event hosted by the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy and the Brookings Hutchins Center on Fiscal and Monetary Policy.

An Innovative Payment Strategy

When a treatment arrives on the market in the United States, the manufacturer takes into account a number of factors when establishing the price. While a low price promotes access, it often fails to adequately reward innovation and value of the new product. As a result, Sood explained, companies set high prices to recover costs and earn a profit. This inherently limits access, especially when the population most affected by the disease is already marginalized and vulnerable socioeconomically as in the case of hepatitis C.

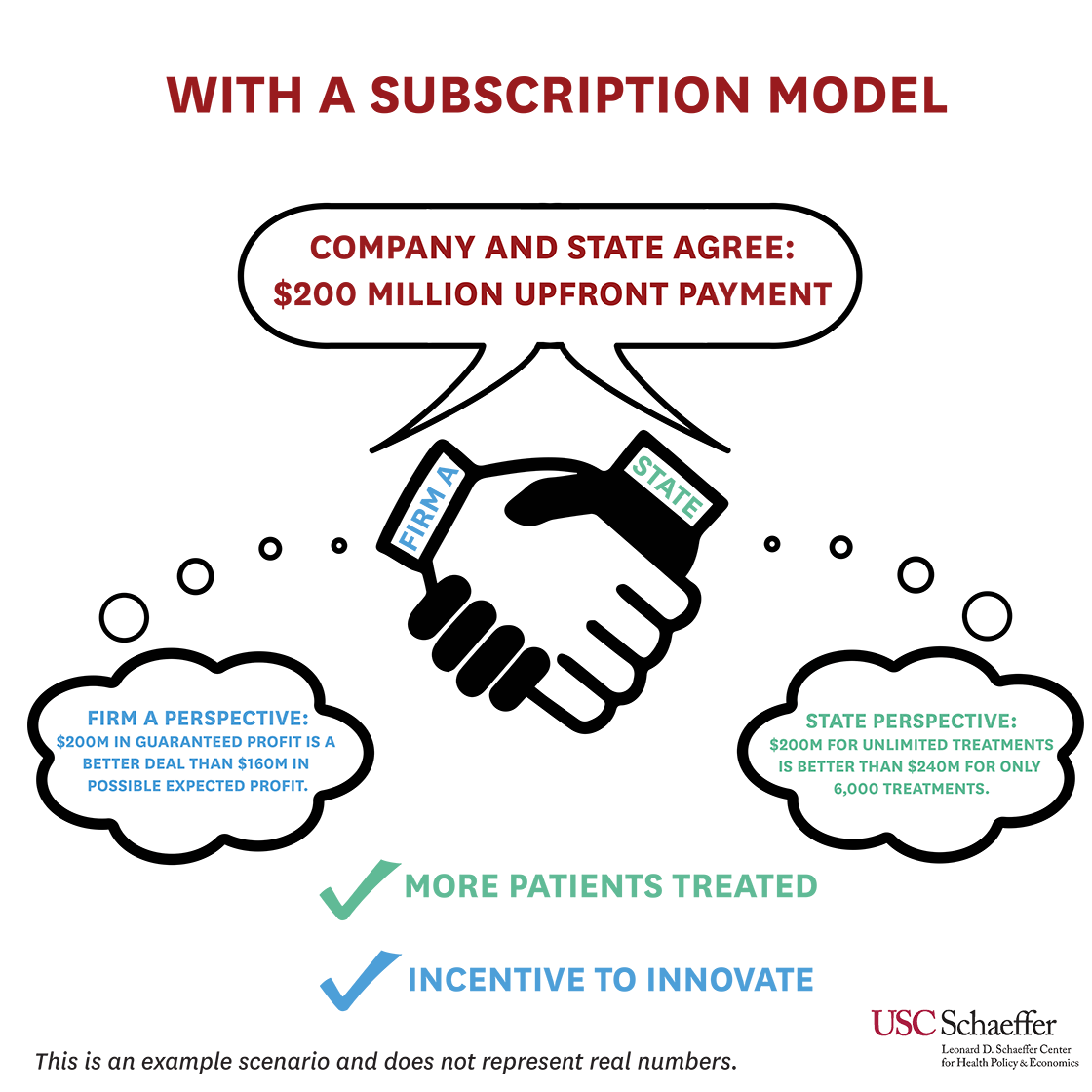

As an alternative, Sood and colleagues on the National Academies panel recommended that the federal government enter into a contract with a single pharmaceutical company that is based on the firm’s expected revenue rather than a typical price-per-pill agreement. The government would pay a lump sum payment and in exchange, the firm provides unlimited treatment for the duration of the contract. Through this arrangement, the company and the purchaser both win: the drug company receives a guaranteed payment on par with expected revenue and the purchaser is able to provide more treatments to patients for less than what would have been paid on a per-dose basis.

Since the release of the report, Sood has worked with experts to establish a state-based strategy, which was published in Annals of Internal Medicine and as a Brookings Policy Brief.

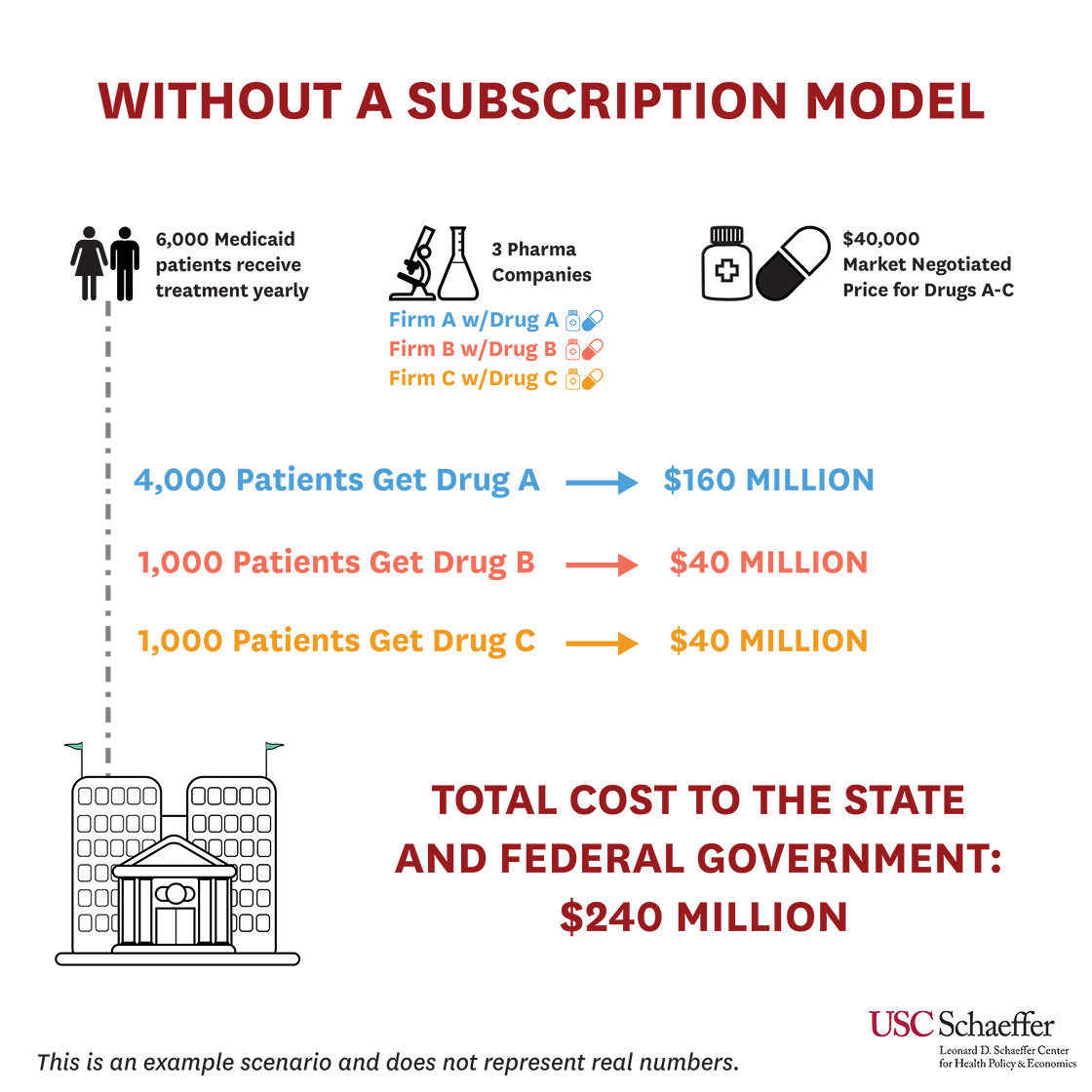

Here is a hypothetical scenario to understand how the numbers add up. Let’s say that under the existing system, only 6,000 patients in a state receive treatment, but there are 250,000 Medicaid patients diagnosed with Hepatitis C. Three different pharmaceutical companies offer the treatment with an average price of $40,000. Between the three companies selling the treatment, the 6,000 patients receive the following:

- 4,000 patients receive their treatment from Firm A at a total cost of $160 million,

- 1,000 receive their treatment from Firm B at a total cost of $40 million, and

- 1,000 receive their treatment from Firm C at a total cost of $40 million.

The total cost to the state and federal government is $240 million.

In the alternative approach – a subscription model, colloquially called the “Netflix” model – the state negotiates a contract with one company to provide all the hepatitis C pill it needs. Using the example above, the state will pay $200 million for unlimited treatment for the duration of the contract. From the company’s perspective, $200 million in guaranteed payment is a sufficient reward for innovation and more than what they would have received under the status quo. From the state’s perspective, $200 million is less than $240 million it would have paid to treat the same 6,000 people, and it will have unlimited access to the therapy.

In the alternative approach – a subscription model, colloquially called the “Netflix” model – the state negotiates a contract with one company to provide all the hepatitis C pill it needs. Using the example above, the state will pay $200 million for unlimited treatment for the duration of the contract. From the company’s perspective, $200 million in guaranteed payment is a sufficient reward for innovation and more than what they would have received under the status quo. From the state’s perspective, $200 million is less than $240 million it would have paid to treat the same 6,000 people, and it will have unlimited access to the therapy. While the above describes a “pure” subscription model, a modified subscription is a more accurate description of what Louisiana has put in place.

While the above describes a “pure” subscription model, a modified subscription is a more accurate description of what Louisiana has put in place.

Louisiana’s Prescription Drug Experiment

Louisiana’s plan, which officially launched July 15, 2019, a week before the Schaeffer Initiative event, is a modified subscription model because the state pays a fixed price per treatment up to a certain cap rather than a lump sum payment to the contracted firm. After reaching that cap, Louisiana will receive additional treatments at no cost through the end of 2024. Louisiana Secretary of Health Rebekah Gee told The New Orleans Advocate that the state hopes to treat at least 30,000 people by 2024 and the goal is to treat 10,000 by the end of 2020.

Within the first week, said Gee at the event, the state already treated hundreds of patients. The real challenge, however, will be getting the word out that treatment is available and identifying people who have the disease and are likely to benefit from the therapy, she acknowledged.

Compared to the status quo of price per pill, the modified subscription model provides greater incentive to treat as many people as possible as any additional person treated after reaching the cap is essentially free. However, they did not want to start a public education program before the contract was finalized to avoid giving patients “false hope.”

State health officials told the Associated Press Louisiana will pay up to $58 million annually for access to a generic form of hepatitis C cure – that is the same amount of money the state spent on hepatitis C treatments during its last budget year for prisoners and Medicaid patients. Alexander Billioux, head of the state public health office, told the AP that the drug co-pay for a Medicaid patient will be no more than $3.

“Price is not the only barrier to expanding treatment,” Sood told an audience. “Even if you make the price zero, you still need to figure out how are you going to test everyone, link them to care, make sure they adhere to therapy and that’s no small task.”

Innovative Payment Strategies: One Size May Not Fit All

Since Louisiana is not required to provide an upfront payment under the plan they negotiated, they will likely pay more overall compared to an authentic subscription model (though still less than the current market price).

This is because of the risk and guarantee – both for the manufacturer and the state – in different types of contracts. Sood outlined the different types of modifications to the subscription model that states could negotiate in his presentation, including a pure subscription model, a modified subscription model, and a volume-based discounts model.

“Which is the model that has the biggest commitment to elimination? The pure subscription model,” Sood explained. “And which is the model that can eliminate hepatitis C at the lowest cost? The pure subscription model.”

“Which is the model that has the biggest commitment to elimination? The pure subscription model. And which is the model that can eliminate hepatitis C at the lowest cost? The pure subscription model.”

But state budgets, Medicaid regulations, politics, and the negotiating power of the state will ultimately play into what policymakers can accomplish.

Sood was asked if the subscription model would work in other markets, and answered most likely, but several conditions must be met. One of the most important factors is the right leadership.

“Can we replicate Rebekah (Dr. Gee) in other states? I don’t know,” he quipped. Sood went on to say this first step by Louisiana is very important. “This is very innovative and you need true leadership to actually implement this.”

A partnership with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is also an essential step. Sood recommends changing Medicaid’s best price rules to make an exception for subscription models in order to streamline the process. CMS should streamline its review, change regulations and laws so that a waiver is not required and provide technical and monetary resources to implement the model, he continued.

Washington, Oklahoma, Michigan and Colorado are currently exploring subscription models to bring hepatitis C and other costly treatments to their citizens. The effectiveness of these and Louisiana’s programs will be watched closely.

“The high cost of prescription drugs is one of the greatest challenges in our healthcare system, and Louisiana’s innovative approach to leveraging a subscription model to promote access to hepatitis C therapy is a great example of how states can lead in designing solutions,” CMS Administrator Seema Verma said in a statement announcing the approval of Louisiana’s state plan amendment for supplemental rebate agreements.

Sood and colleagues at the Schaeffer Center have conducted research on a number of other alternative payment strategies, including value-based pricing and licensing agreements, recognizing that innovative payment strategies will be increasingly necessary as new cures and medicines are discovered.

You must be logged in to post a comment.