Editor’s Note: The originally ran in STAT on 8/26/2016

Mylan Pharmaceuticals is at the center of a firestorm of criticism over dramatic price hikes for its lifesaving EpiPen. The problem, says Mylan CEO Heather Bresch, is a broken health system that has let deductibles and copays skyrocket on many insurance policies.

She is half right. If deductibles had stayed low, parents and other EpiPen users probably wouldn’t have noticed that Mylan had increased the price of a two-injector set from around $100 seven years ago to more than $600 this spring. But their insurance companies were still getting gouged.

The real problem isn’t with insurance design. It is lax regulatory oversight that doesn’t ensure an adequate supply of drugs critical to population health and opens the door to shocking price increases.

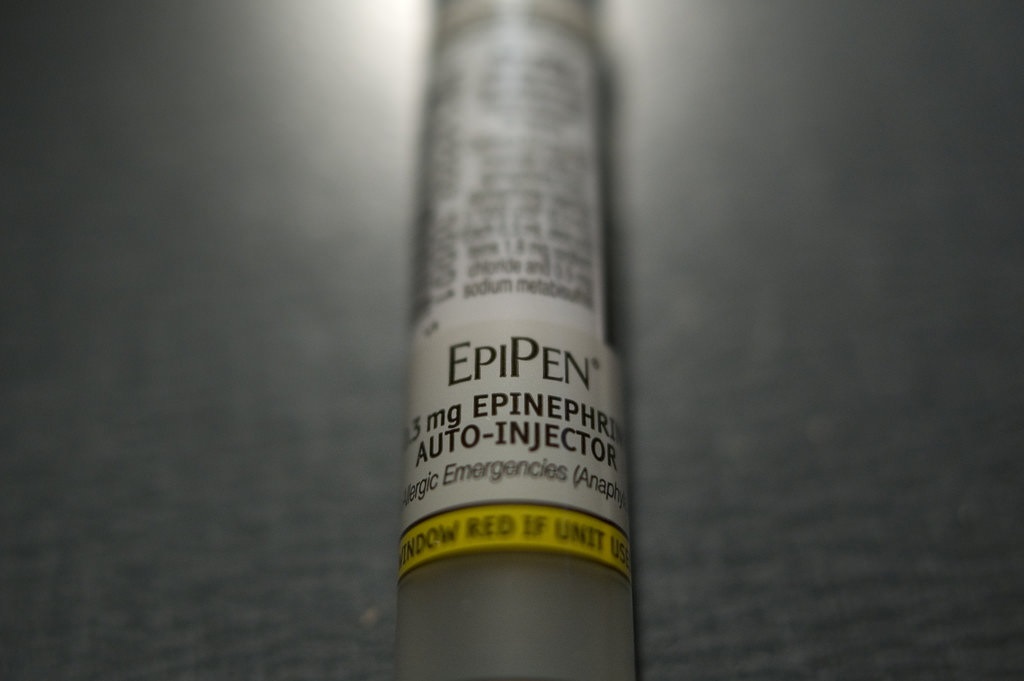

The EpiPen is the overwhelming choice to keep kids and others safe from anaphylactic shock that can be triggered by food allergies and insect bites. You use it by pressing it against the thigh, which automatically injects a preset dose of epinephrine. That’s a much-needed update to using a syringe and vial, which wastes precious seconds and risks misdosing. Parents usually buy several EpiPen sets a year to have ready whenever and wherever needed, and to make sure the medicine hasn’t expired. Schools also buy lots of EpiPens.

Epinephrine is not a new drug. In fact, its properties were discovered more than 100 years ago, and Parke-Davis — one of the largest pharmaceutical companies at the time — started marketing it under the brand name Adrenalin soon after that. The development of the auto-injector in the 1970s with a predetermined dose was a breakthrough.

Mylan couldn’t hold a patent on epinephrine, but it could on an auto-injector. This meant it could exercise its government monopoly when it bought the drug and device from Merck and started marketing the EpiPen in 2007.

French competitor Sanofi entered the market with a different type of auto-injector in 2013, but recalled the product in the United States and Canada in 2015 after reports of 26 adverse events, with no fatalities. At that time, Sanofi had already sold 2.8 million units — suggesting a failure rate of less than 0.01 percent.

Rather than working to keep Sanofi in the game, US officials sat on the sidelines as Mylan’s market power grew. This spring, the FDA rejected a knockoff injector made by Israel-based Teva Pharmaceuticals, putting Mylan in position to control 95 percent or more of the market.

So what can we do? US officials must get off the sidelines. They need to understand that sometimes it is worth taking a manageable risk to ensure adequate supply of a necessary medication. In fact, such a model already exists for vaccines.

Each year the federal government buys billions of dollars’ worth of vaccines and stockpiles them for current and future use. This process creates and maintains stable markets for vital vaccines.

For essential products such as auto-injected epinephrine — and other indispensable generic drugs — a three-stage sequence could emulate the vaccine model.

First, Congress should mandate that the Federal Trade Commission report on the availability of all such drugs and devices by identifying all the companies that make them and how they are being supplied to hospitals and pharmacies.

Second, the Food and Drug Administration should examine the FTC report to discover which essential products have competition or supply issues. When supplies are limited — epinephrine has been on a drug shortage list since 2012 — the FDA should be given new authority to allow foreign imports to solve the immediate crisis. In the case of the EpiPen, that would result in prices roughly one-quarter of Mylan’s US listed retail charge.

Finally, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, which has experience buying vaccines to prevent supply problems, should be authorized to begin buying essential generic drugs and devices on behalf of federal users, including Veterans Affairs, Medicaid, and Medicare.

Such purchases would assure potential competitors that a steady market exists worthy of investing in production lines. At the same time, renewed competition and new government stockpiles would act to keep prices from rising.

The current EpiPen imbroglio, which has reached even into the presidential campaign, may yet force Mylan to cut list prices. But that momentary salve should not delude us into thinking we can solve the problem of unstable drug pricing by shaming one company. Healthy competition among multiple suppliers is the best answer to prevent high prices.