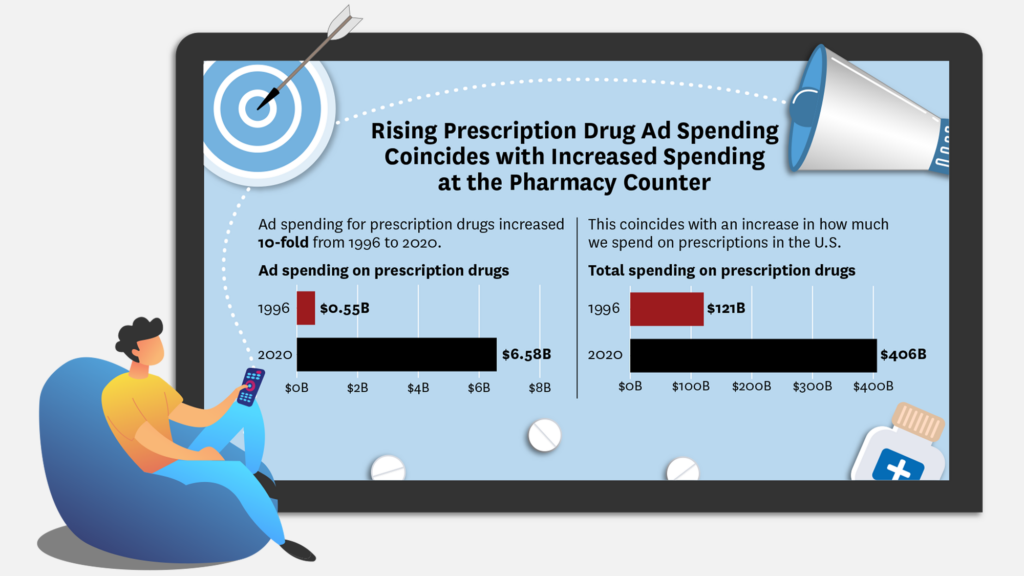

The U.S. and New Zealand are the only countries that allow direct-to-consumer prescription drug advertisements. In the U.S., television viewers are subjected to an especially increasing volume of drug commercials. In 1996, $550 million was spent by pharmaceutical companies on drugs ads. That number increased more than 10-fold by 2020, reaching $6.58 billion annually.

Concern is rising that the boom in ads leads to:

- Use of more expensive branded medication, which are more often featured in commercials, rather than generic options.

- Less interest in nonpharmacologic treatments, including lifestyle changes and healthy behaviors.

- Inappropriate drug prescribing through patients asking for unnecessary drugs they have seen in advertisements.

Conversely, others argue that these types of drug ads serve a public good by:

- Educating consumers about possible treatment options about illnesses or diseases that may not be top-of-mind for patients.

- Increasing engagement and treatment initiation with advertised drugs or their generic counterparts.

- Encouraging medication adherence.

While policymakers are considering different regulations for direct-to-consumer advertisement as the media landscape changes, it’s important that they are clear about what the problem is and what the unintended side effects of the proposed solution might be.

Starting in 2015, I worked with researchers from the University of Southern California, Johns Hopkins, Cornell University and Wharton to study the effects of pharmaceutical direct-to-consumer advertising to better understand what effect, if any, these ads were having on patient behavior and outcomes. Below are six takeaways from the research.

1. Prescription drug use is impacted by pharmaceutical ads

We used the implementation of Medicare Part D as a natural experiment to study the effects of advertising. Medicare Part D is the prescription drug benefit. When it started, we saw an increase in advertising in areas with a high fraction of Medicare-eligible consumers (such as Florida) relative to area with relatively few older adults (such as Colorado). We hypothesize that the increased exposure to advertising should increase drug utilization of the younger adults living in areas with a high proportion of Medicare-eligible viewers.

We find that drug utilization is highly responsive to advertising exposure with a 6% increase in the number of prescriptions purchased by the non-elderly in areas with a high Medicare-eligible share, relative to areas with a lower share. Furthermore, about 70% of this increase was driven by new prescriptions and the remaining 30% was driven by increased adherence for existing patients. We also find that those who initiate treatment due to advertising are on average less adherent, which suggests that some of the increase in utilization might be unnecessary.

2. Patients exposed to prescription drug ads were more likely to seek out doctor appointments and continued to see their doctor for multiple years

Pharmaceutical commercials seem to serve as a reminder or nudge to set up an appointment with a primary care doctor.

An analysis of Neilson advertising data and claims data from 40 large national employers showed that exposure to advertising lead to an increase in the number of office visits each year. Furthermore, patients who visit their doctor after seeing a pharmaceutical ad typically continue with additional follow-up visits. This impact appears to last up to four years after the initial doctor visit with a drop in the frequency of visits over time.

3. Less expensive generic brands are still prescribed despite ads promoting branded medications

Despite concerns that direct-to-consumer ads would push patients toward more expensive branded medications, we see that this is not the case in most scenarios. We find the increased number of office visits due to direct-to-consumer ads usually resulted in a prescription for a generic drug or a non-drug treatment.

4. While exposure to ads increased medication-related demand, patients don’t indicate they’ll stop healthy lifestyle behaviors

When patients with high cholesterol or who are currently cigarette smokers, overweight or obese were shown drug ads, patients indicated a slight increase in interest in these medications and getting information about them. But importantly, exposure did not seem to be correlated with a decreased interest in engaging in non-pharmaceutical lifestyle interventions like exercising and eating a healthy diet. Study participants exposed to drug ads were more likely to have favorable perceptions of the importance of health and exercise compared to those exposed to non-pharmaceutical TV commercials.

5. Disclosing price does not seem to impact individuals’ view of the advertised drug

In the study mentioned above, some of the pharmaceutical ads provided information about the cost of the drug while others did not. We found no significant difference in the effect of the ad among viewers who had cost information and those who didn’t, though the drug advertised was not a high-cost drug.

While this result is at odds with prior results from a recent study that looked at the effect of showing a high-priced drug to consumers, it is in line with the broader literature about price transparency in healthcare, which has shown that publicly available information about price does not shift demand.

6. Drug companies benefit from these ads

As much as a third of drug expenditure increases can be linked to the prevalence of drug ads. There was a positive association between exposure to drug advertising and intention to switch medications or engaging in behavior to find out more about the medication. Consumers exposed to advertising were also more likely to have more favorable views about the innovativeness and competence of the pharmaceutical industry.

Our research suggests that advertising benefits both consumers and companies advertising the products. Consumers benefit through increased adherence to medications, greater engagement with the healthcare system and use of generic medications. Companies benefit from greater sales of their products and more favorable consumer opinions of the industry. We did not find much evidence that advertising discouraged healthy lifestyles or other non-drug treatments. We also found that price disclosures in advertisements, which have been suggested by policymakers, will have little effect on consumer behavior.

In short, restrictions on advertising are not a silver bullet for reducing inappropriate use of drugs because these restrictions will also likely reduce appropriate use and reduce patient engagement. This body of research suggests that policymakers should proceed with caution as they design proposals to restrict advertising.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news