Editor’s note: This perspective was originally published by Health Affairs on March 23, 2020.

When patients access hospital emergency departments (EDs), they receive services and receive separate bills from two sets of providers: (1) physicians (including emergency room doctor and other hospital-based specialists, as needed); and (2) the hospital, for use of its ED facilities and staff and any other departments within the hospital that provided other services, such as lab and x-ray. Surprise physician bills occur when patients with insurance coverage seek emergency care in approved and contracted, in-network hospitals, only to find out (often later) that the ED physicians (and other hospital-based physicians) and the charges for their services are not part of the approved, contracted network for their plan. In these cases, non-contracted physicians can bill patients directly (balance billing) and/or bill their insurance company for supplemental charges above the amounts that their health plan approved for the out-of-network services.

In policy discussions and blog posts surrounding out-of-network emergency billing practices, much of the attention has focused on “surprise bills” from out-of-network hospital-based physician specialists (ED physicians, anesthesiologists, radiologists, pathologists, and hospitalists). This post focuses on the need and options to regulate hospital out-of-network emergency prices. We use data from California, a large state with a large number of hospitals operating under a variety of market conditions, to conduct a detailed analysis of the need to regulate hospital out-of-network emergency prices and potential benchmarks for setting hospital out-of-network emergency prices.

While the incidence of surprise hospital bills for emergency services is lower than for physician ED services, the inflationary dynamics of unregulated out-of-network emergency prices for hospital services are the same, if not greater—providers use the threat of leaving plan networks and demanding prices based on full billed charges to gain higher in-network prices. This leads to higher health insurance premiums for everyone, not just emergency patients.

The potential savings from limiting out-of-network hospital emergency prices are likely substantial. A recent study published in Health Affairs estimated that capping out-of-network physician prices “would lower physician payments for privately insured patients by 13.4 percent and reduce health care spending for people with employer-sponsored insurance by 3.4 percent.” Savings from limiting out-of-network emergency hospital prices are likely much larger than for physician services since hospital spending is about 30 percent of total spending for privately insured populations compared to the 1 percent of spending accounted for by ED physicians.

Policy Background

One of the most contentious issues in policy discussions so far has been selection of the appropriate benchmark for setting out-of-network hospital emergency prices. Recent discussions in Congress included a proposed benchmark tied to in-network, contracted rates where health plans would “pay (hospital) providers the median in-network contracted amount that insurers have negotiated with other providers in that geographic area.” Alternatively, proposed legislation in California included a benchmark tied to Medicare rates—the prices a hospital could charge for its non-contracted ED services were “limited to 150 percent of the Medicare price or the average contracted rate in the area, whichever is greater.”

Hospitals have argued that these proposed benchmarks are too low and will give health plans excessive leverage during in-network contract negotiations, resulting in a form of back door rate regulation. They also argue that reliance on average market rates unfairly penalizes higher- priced hospitals that may have higher quality or provide more advanced services that result in higher operating costs and justify above average market prices. Further, providers argue that, by relying on health plan databases to calculate average in-network rates (mean or median), health plans will have a strong incentive to cancel higher priced in-network contracts in order to lower benchmark rates applied to out-of-network emergency transactions.

Our analysis shows that providers arguments have merit Setting prices too low for out-of-network emergency services could be highly disruptive by shifting the leverage too far in favor of health plans.

We propose an alternative, more generous benchmark that caps out-of-network hospital emergency prices at 160 percent of each hospital’s own actual costs. This scales payment to each hospital’s own costs and guarantees each hospital a 60 percent profit margin for its out-of-network emergency services. We find that using this benchmark could solve many of the problems associated with current hospital out-of-network emergency pricing practices without creating excessive market disruption.

How Unregulated Out-Of-Network Prices Endow Hospitals With Excessive Negotiating Power and Thus the Need to Regulate Out-Of-Network Hospital Emergency Prices

For most commercially insured Americans, the prices they or their health plans pay hospitals (on their behalf) are determined by negotiations between their insurance companies and hospitals. A hospital, when negotiating for higher “in-network” contract rates, can threaten to cancel their contracts, become out-of-network for the plan, and then use their much higher billed charges as the price to charge the plan for its emergency patients who use the hospital.

Several factors have made the threat that hospitals will “go out of network” more powerful in the contract negotiation process and have contributed to rising hospital prices for all patients (both in and out-of-network) and contributed to rising health insurance premiums for all:

- Federal and state regulations designed to assure access to needed emergency services require hospitals to treat all emergency patients who come to their ED, and health plans are required to pay for emergency care for their members even if care is received in non-contracted, out-of-network hospitals. These regulations have contributed to substantial growth in hospital-based emergency services.

- Research shows that hospital EDs have become the primary source of inpatient admissions and that EDs are the major driver of overall economic activity for acute care hospitals.

- Hospitals typically demand their full, billed charges as payment for out-of-network emergencies.

- Hospital billed charges are set unilaterally by each hospital without external regulation or market constraints and as a result have become highly inflated (hospital billed charges average 250-plus percent of costs for US hospitals)

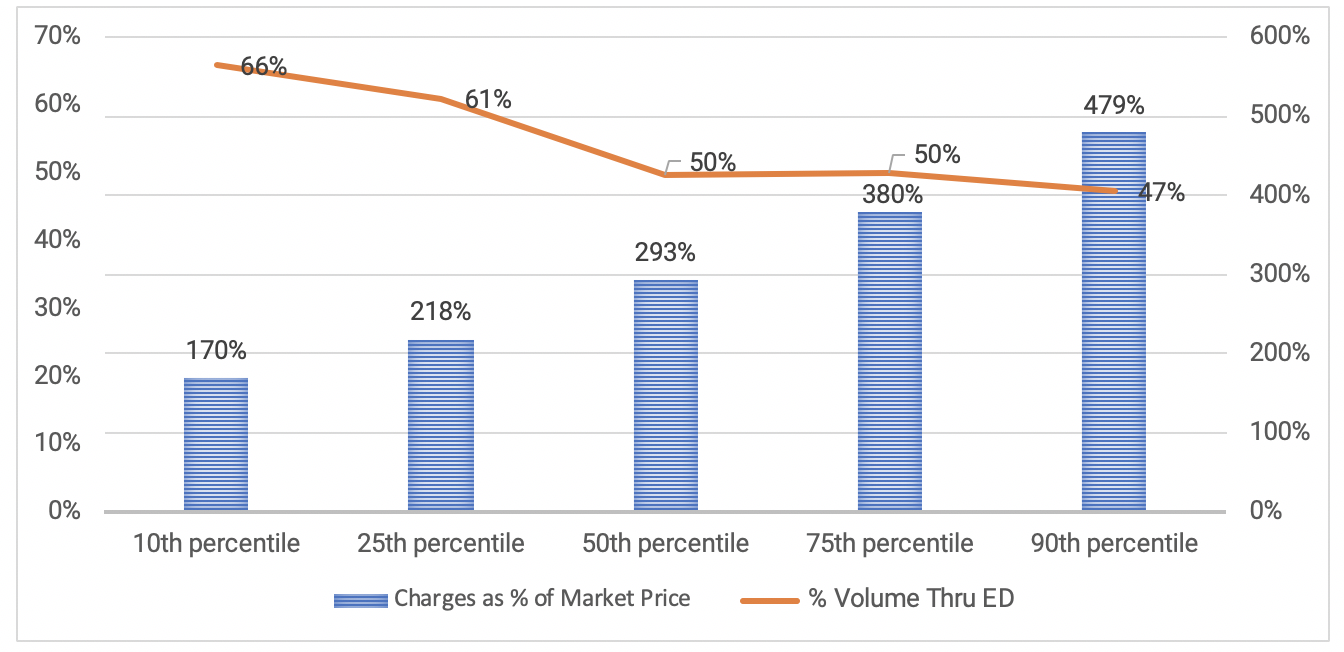

Exhibit 1 below (based on California hospital data, 2016) summarizes the effects of increased demand for hospital emergency services and rising hospital billed charges. Hospital billed charges range from 170 percent to 479 percent of market prices while most hospitals have 50 percent or more of their inpatient volume entering through their EDs.

Exhibit 1: Hospital ED Charges and Percent of Patient Volume Coming Through ED

Source: California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, 2016.

The implications of these statistics are documented in recent research that shows that hospitals can cancel their commercial health plan contracts and substantially raise their prices (based on their billed charges) to commercial health plans for out-of-network ED care and still retain 50 percent of their ED volume for up to two years, despite being out of network. The ability of hospitals to cancel their contracts, retain a large share of their ED volume, and substantially raise their prices means that even hospitals with a low share of their volume coming through their ED can retain enough non-contracted ED volume to increase their own profits and at the same time impose an in increase health plan costs by going out-of-network.

In sum, under current conditions, hospitals have substantial negotiating leverage over health plans to increase in-network rates by threatening to cancel their contracts and demanding their high billed charges along with the likelihood that that they will retain a large share of health plan’s emergency patients despite being out-of-network.

Benchmarks

One of the most controversial and contentious issues in policy discussions so far has been selection of the appropriate benchmark for setting out-of-network emergency prices. Recent Congressional discussions included a proposed benchmark tied to in-network, contracted rates, “where health plans would pay providers the median in-network contracted amount that insurers have negotiated with other providers in that geographic area.” Proposed legislation in California included a benchmark tied to Medicare rates, “where the prices a hospital could charge for its non-contracted ED services were limited to 150 percent of the Medicare price or the average contracted rate in the area, whichever is greater”.

Hospitals have argued that these proposed benchmarks are too low and will give health plans excessive leverage during in-network contract negotiations, resulting in a form of back-door rate regulation. Further, providers argue that that by relying on health plan databases to calculate average in-network rates (mean or median), health plans will have a strong incentive to cancel higher priced in-network contracts to lower benchmark rates applied to future out-of-network emergency transactions. They also argue that reliance on average market rates unfairly penalizes higher-priced hospitals that may have higher quality or more advanced services that result in higher operating costs and justify above-average market prices. These arguments have merit: setting prices too low for out-of- network emergency services could be highly disruptive by shifting the leverage too far in favor of health plans.

As an alternative, we test a more generous benchmark that caps out-of-network hospital emergency prices at 160 percent of each hospital’s own actual costs (guaranteeing each hospital a 60 percent profit margin for its emergency services based on its own costs) and find that it could solve many of the problems associated with current hospital out-of-network emergency pricing practices without creating excessive market disruption.

Assessment Of Benchmarks

The policy goal is to prescribe a benchmark and process to determine out-of-network emergency hospital prices which removes excess leverage on both sides but also minimizes distortions and disruptions to on-going contract and price negotiations between hospitals and health plans. If the benchmark is set too high, hospitals with market prices below the benchmark may have an incentive to cancel their contracts with health plans and go out-of-network to increase their profits. Alternatively, hospitals have argued that if the benchmark is set too low the price caps become a form of de facto rate regulation and that health plans will cancel contracts with hospitals in order to take advantage of below-market regulated prices.

Market-Based Benchmark

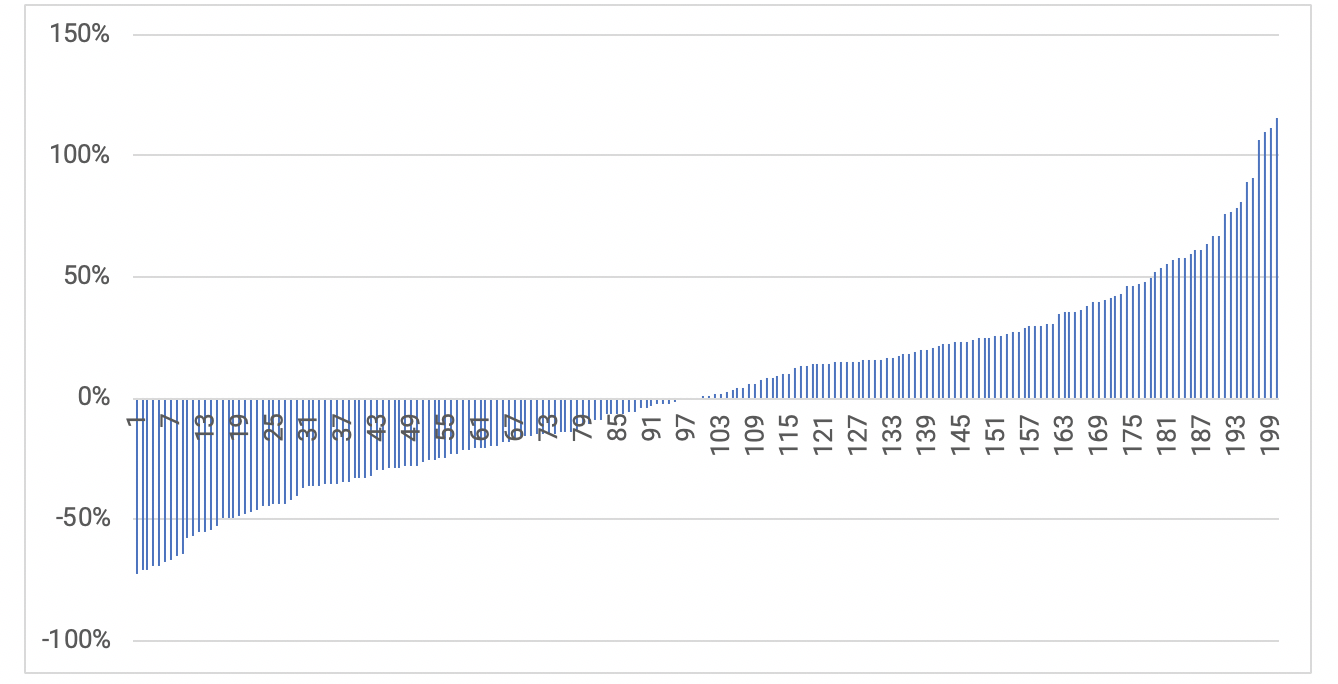

A market price (median) based benchmark has the value of being tied to the market and reflects market forces that drive hospital-health plan negotiations. However, because of the wide variation in hospital market prices (Exhibit 2), applying a market average (or median) to all hospitals has the potential to be highly disruptive and to create incentives that will distort hospital-health plan negotiations.

Exhibit 2: Hospital Market Price (Adjusted for Case Mix and Medicare Wage Index): Percent Difference From Median

Source: California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, 2016.

As can be seen, current hospital market prices vary substantially (even after adjusting for case mix and input prices) and as such many hospitals have prices that are far from the median value. Hospitals argue that using a market average (or median) does not adequately capture hospital differences and could penalize hospitals that where higher costs lead to higher quality and thus justify higher prices (above the median). In addition, depending on how it is implemented, the database required to calculate market rates could be manipulated by either hospitals or health plans to influence the benchmark (and ultimately, in network rates); over time, the underlying market price database used to calculate benchmark values would change depending on the evolving mix of the contracted hospitals and their prices. For example, if health plans systematically removed higher-priced hospitals from their networks at a greater rate, the benchmark value would fall, which would increase health plan contracting leverage vis-à-vis all hospitals.

Cost-Based Benchmark

As an alternative, we tested a cost-based benchmark that ties regulated rates to each hospital’s own cost structure, which reflects both local market forces and individual hospital characteristics. This is less subject to database manipulation, while at the same time providing a predictable benchmark that reflects market forces and each hospital’s cost structure. Medicare currently uses a cost-based benchmark to reimburse hospitals for extremely expensive “outlier” patients, and Medicare Advantage plans cap payment for out-of-network emergency admissions at the Medicare Fee for Service rate (which is benchmarked, in part, to hospital costs).

We analyzed a benchmark tied to each hospital’s actual total operating costs (per adjusted discharge) multiplied by a factor of 1.6 to reflect current average of market rates to hospital costs in California in order to minimize disruption to the market (commercial market rates in California are paid, on average, at 160 percent of costs). This benchmark could be calculated using publicly available data reported by hospitals to Medicare and would not require health plans to develop detailed databases or methods to calculate rates for each hospital, although a database would be needed to recalibrate the multiplicative cost factor over time, to reflect changes in hospital costs and prevailing market rates (i.e., to evaluate whether 160 percent of costs is continues to be the right factor).

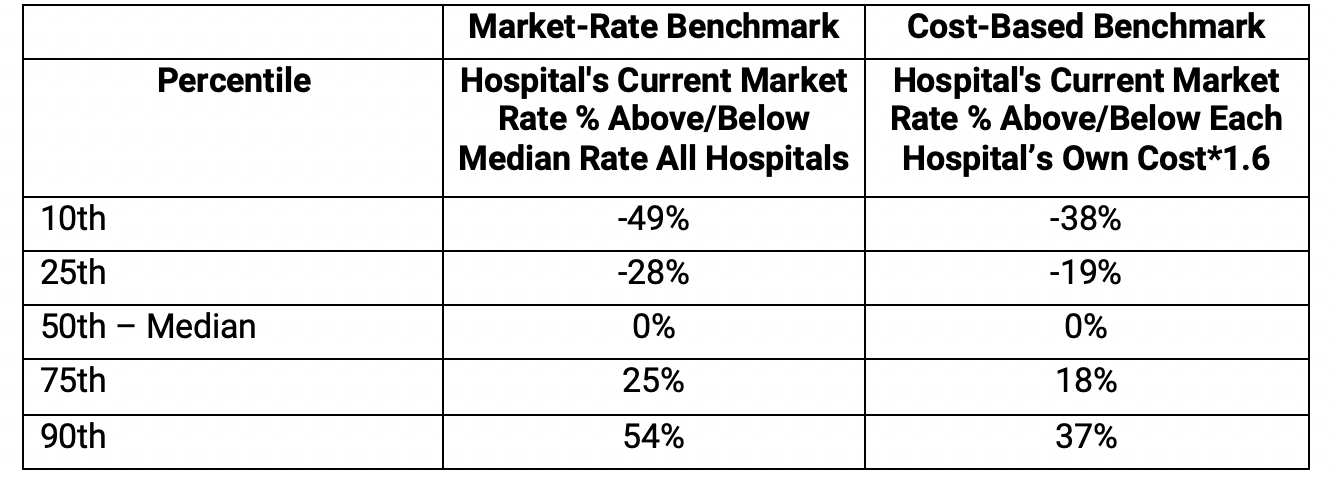

Exhibit 3 below (using California hospital data) compares the distribution of hospitals for the two benchmarks. The greater the distance from the benchmark, the greater the incentive for either hospitals and/or health plans to cancel commercial health plan contracts in order to replace their existing market rates with more favorable benchmark rates.

Exhibit 3: Distribution of Hospitals Across Benchmarks, Costs, and Charges

Source: California Office of Statewide Health Planning and Development, 2016.

While both benchmarks have a wide distribution, the benchmark based on each hospital’s costs has a narrower distribution. For example, lower-priced hospitals (25th percentile) have market rates that are 28 percent below the median market rate but are only 19 percent below the cost-based benchmark, providing less of an incentive to cancel contracts to gain the benchmark rate for their retained volume. A similar narrowing of the difference from the benchmark is observed for hospitals with higher-priced hospitals, where at the 75th percentile the average difference 18% based on the cost-based benchmark compared 25 percent using the median market rate.

Summing Up

Our analysis shows that by demanding their high billed charges, along with the likelihood that that they will retain a large share of health plan’s emergency patients, many hospitals have substantial negotiating leverage over health plans by threatening to cancel their contracts. Our data show that a high-priced hospital (75th percentile) could cancel its contract, lose almost two-thirds of its volume, and still receive 90 percent of its pre-cancellation revenue from commercial payors, resulting in increased hospital profits and increased health plan costs. Capping out-of-network rates using either benchmark substantially reduces hospital leverage from charging billed charges for out-of-network emergency patients. The cost-based benchmark achieves this goal but: 1) is likely to be less disruptive to the market, 2) is likely to be seen as less arbitrary and unfair since it is tied to each hospital’s own costs and guarantees a 60 percent profit margin for out-of-network emergency patients, and, 3) is much easier to administer as it relies on existing data that are routinely reported to Medicare.

In summary, and contrary to hospital arguments, capping out-of-network hospital emergency prices can restore competitive balance to the market without shifting leverage too far in favor of health plans. Under price caps, the incentives for health plans to cancel contracts with high-priced providers do not depend solely on the benchmark but will also depend on the prices of competing hospitals that might serve as a substitute for the plan’s network—if the plan can move its patients to another hospital that offers a lower negotiated price, it can now do so without incurring the exorbitant out-of-network penalty tied to billed charges. This restores price competition.

The potential cost savings to a health plan, however, is only one factor driving that decision as health plans must consider the importance of the hospital to its network and the marketing of their product within the health insurance market. Thus, competitive market forces, without the distortions from excessive out-of-network pricing, will determine the outcome of this process.

You must be logged in to post a comment.