A new study led by Sophie Terp, an emergency medicine physician at LA County USC Medical Center, found that nearly one in five settlements related to the Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA) involved psychiatric emergencies and these settlements have been significantly larger than settlements not involving psychiatric emergencies. Furthermore, the proportion of settlements related to psychiatric emergencies has increased in recent years, suggesting the need for more resources to improve access and quality of care for patients with psychiatric emergencies.

The study was published online April 17 in Academic Emergency Medicine.

“Recent high-profile cases have drawn attention to the issue of patient dumping as it relates to psychiatric emergencies, but there hasn’t been prior analysis of the frequency or magnitude of civil monetary penalties related to EMTALA cases involving psychiatric emergencies,” said Terp. “As the number of patients presenting to emergency departments with psychiatric emergencies increases, these penalties may be an important indicator of adequacy of psychiatric emergency care.”

Terp is a clinical fellow at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics and an assistant professor of clinical emergency medicine at the Keck School of Medicine of USC.

The Emergency Medical Treatment and Labor Act (EMTALA)

EMTALA was landmark legislation passed by Congress in 1986 establishing that emergency departments (EDs) had a responsibility to provide screening exams and stabilization of emergent conditions to patients requesting care regardless of ability to pay. EMTALA was passed in response to a series of high profile incidents of inadequate, delayed or denied treatment of uninsured patients by EDs, and intended to stop the practice of patient “dumping” (refusing or transferring financially disadvantaged patients without appropriate stabilization).

The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) can cite hospitals for non-compliance with the law, and the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) can issue civil monetary penalties to hospitals found to be in violation of EMTALA. EMTALA is actively enforced. In 2017, Terp led a study evaluating trends in enforcement of EMTALA, finding that more than a quarter of hospitals were issued citations for EMTALA violations between 2005 and 2014.

In recent years, CMS has clarified that EMTALA applies not only to medical emergencies, but to psychiatric emergencies as well.

Cases Involving Psychiatric Emergencies Are Substantial and Growing Share of Citations Levied

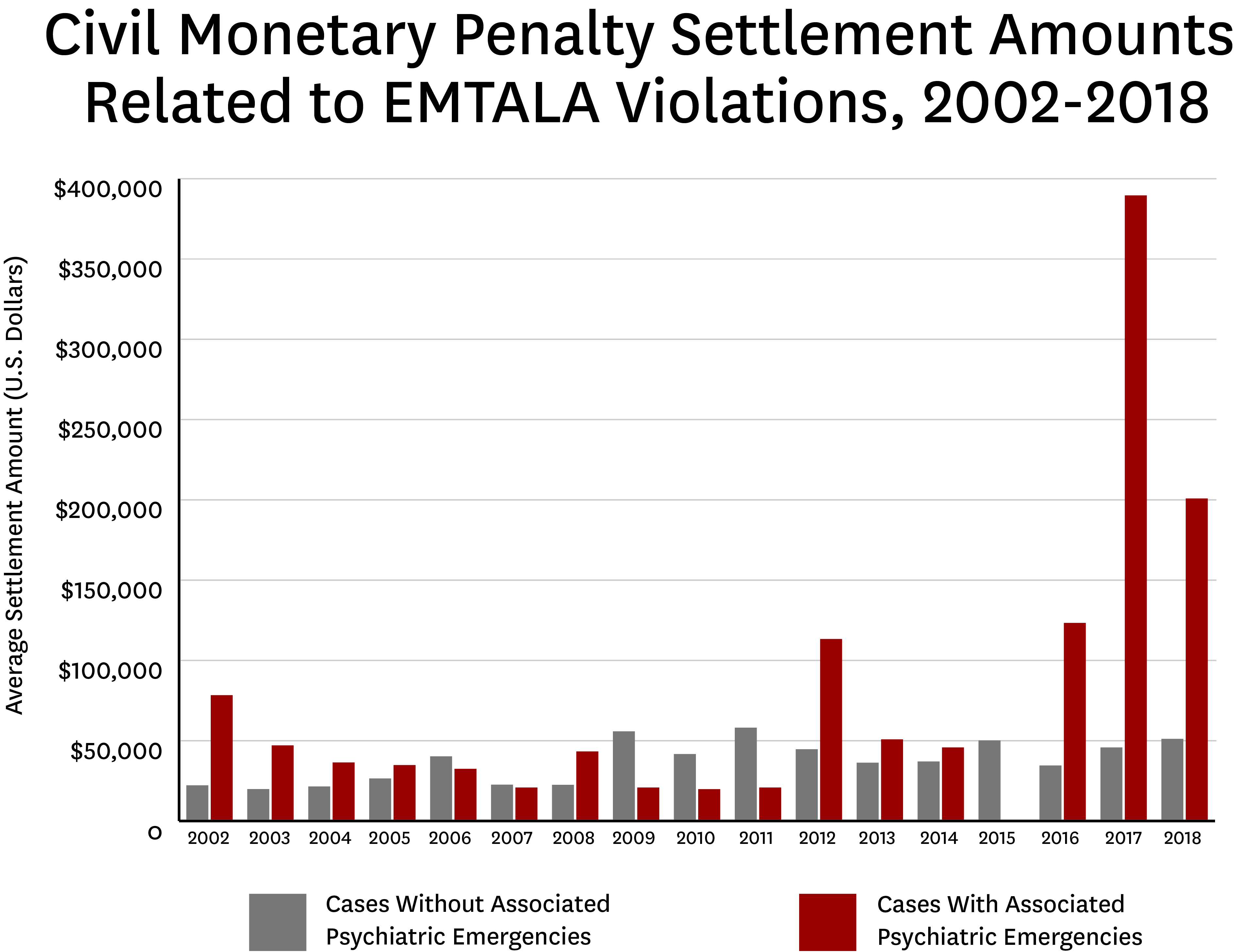

Terp and colleagues analyzed 230 civil monetary penalty settlements related to EMTALA violations issued between 2002 and 2018. They found 19 percent of EMTALA related settlements involved psychiatric emergencies, increasing from 18 percent in the first 14 years of the study period to 26 percent between 2016 and 2018.

The average settlement amount for a psychiatric-related case was $85,488, more than double the average settlement for a non-psychiatric violation ($32,004). The three largest settlements during the study period involved psychiatric emergencies and occurred in recent years.

The researchers look at the largest settlement agreement, for $1.3 million in 2017, which involved a South Carolina ED where the OIG identified 36 incidents of individuals presenting to the ED with unstable psychiatric conditions who were involuntarily committed and kept in the ED for between 6 and 38 days. In this case the hospital was cited for multiple instances of failure to provide appropriate medical screening exam, stabilizing treatment and appropriate transfer. Notably, the hospital was cited for failing to admit involuntarily committed psychiatric ED patients to available beds in the hospital’s behavioral health unit that historically, by policy and practice, only admitted voluntary patients.

“The CMS determination that ED in this case should have admitted involuntarily committed patients to their behavioral health unit that had a policy of only admitting voluntary patients raises the question of whether other hospitals boarding involuntary patients in their EDs might be cited for failing to utilize available inpatient beds restricted by policy to voluntary or geriatric patients in the future,” explained Terp.

Lack of Access to Mental Healthcare and Resources May Be Driving These Trends

In the past two decades, patients seeking treatment for mental health emergencies have comprised a significant and growing proportion of ED visits. This has unfortunately coincided with a decline in the number of available inpatient psychiatric beds.

“Ultimately, the shortage of inpatient psychiatric beds available for patients requiring stabilizing psychiatric treatment places EDs in the precarious position of boarding patients on involuntary psychiatric commitments for days or even weeks until inpatient beds can be identified,” said Terp. “EDs are suboptimal long-term venues of care for patients experiencing acute psychiatric crisis. The scarcity of inpatient psychiatric beds is central to the crisis of psychiatric care in EDs.”

All told, 68 percent of cases involving psychiatric emergencies involved citations for failure to provide stabilizing treatment. In addition, common causes for citations included failure to arrange appropriate transfer and failure to provide a medical screening exam.

The researchers found half of all settlements involving psychiatric conditions occurred in three states- Florida, North Carolina, and Missouri. Though, it is unclear if this reflects regional variation in access to emergency psychiatric care or differential enforcement in these areas.

In addition to Terp, study authors include Brandon Wang (New York University School of Medicine), Elizabeth Burner (Keck School of Medicine of USC), Denton Connor (Creighton University School of Medicine), Seth Seabury (USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics) and Michael Menchine (Keck School of Medicine of USC). This research was initiated while Terp was supported by an F32 Postdoctoral Training Award from AHRQ (F32 HS022402-01).

You must be logged in to post a comment.