Patients with opioid addiction have long relied on in-person group or individual therapy as well as group support for sustained recovery. At the onset of the pandemic, these activities became too dangerous to do in person, leaving many patients and those in recovery feeling isolated at a particularly vulnerable time.

Recognizing the risks of suspending treatment and recovery support during pandemic-related shutdowns, state and federal governments adjusted policies to facilitate remote access to treatment and systems of care. As with other policy changes, each state took a different approach.

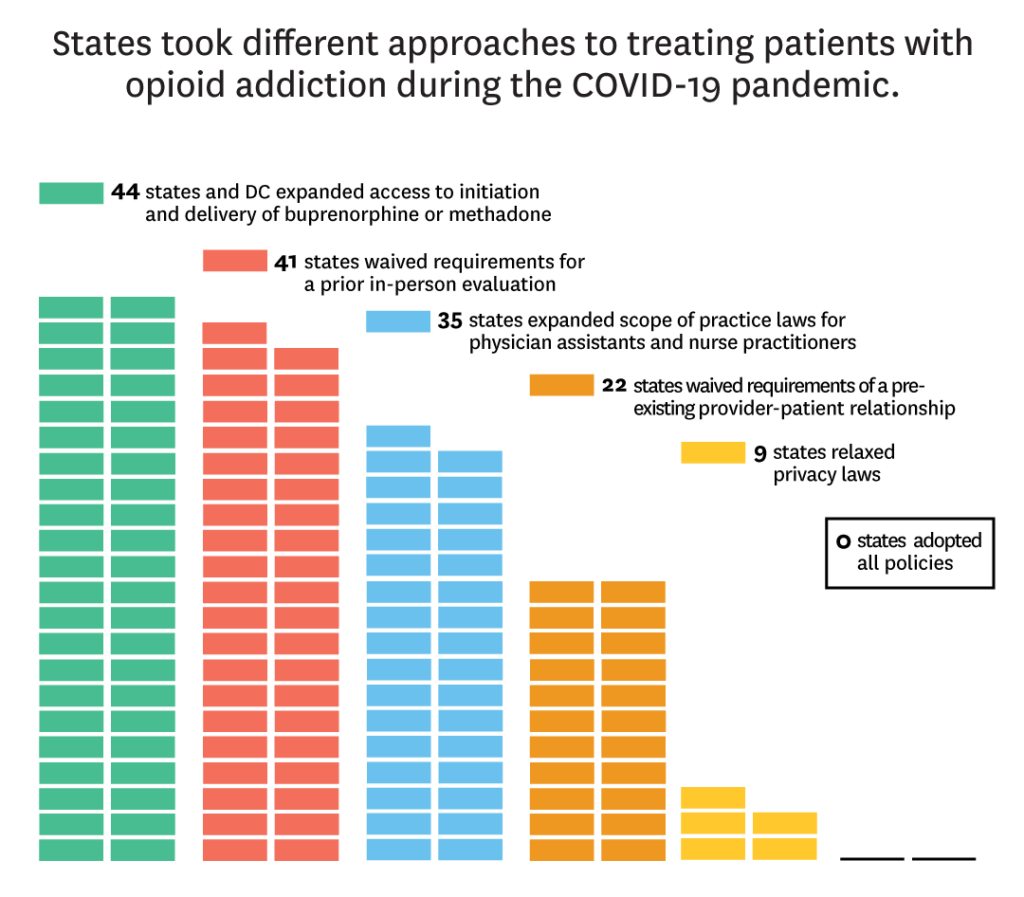

A new study in JAMA Health Forum by USC Schaeffer Center experts analyzes state and federal responses to the opioid crisis amidst the pandemic. The authors find that while all states and D.C. have adopted at least one policy related to treatment access for patients suffering from opioid addiction, zero states adopted all policies important to treatment access.

“It’s important for lawmakers and researchers to understand that the local effects of these policies may differ given variation in the number and types of barriers remaining,” said Rosalie Liccardo Pacula, senior fellow at Schaeffer Center and Elizabeth Garrett Chair in Health Policy, Economics & Law and the USC Price School of Public Policy.

Removing barriers to opioid addiction treatment that existed before the pandemic

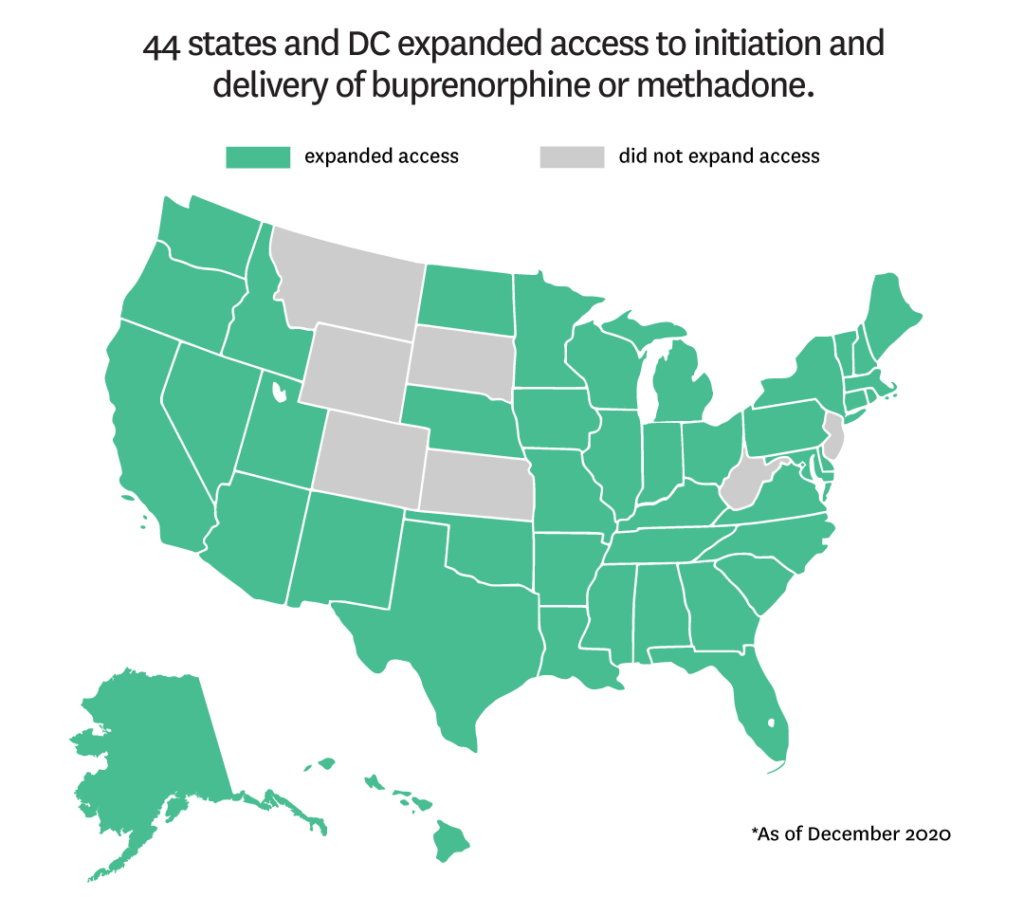

Prior to COVID-19, telehealth was a promising, yet underutilized tool for supporting patients with opioid addiction. Up to 40% of U.S. counties lack a physician authorized to prescribe the opioid treatment drug buprenorphine, and at least 18% of people live 30 minutes or more from the nearest opioid treatment program to access methadone.

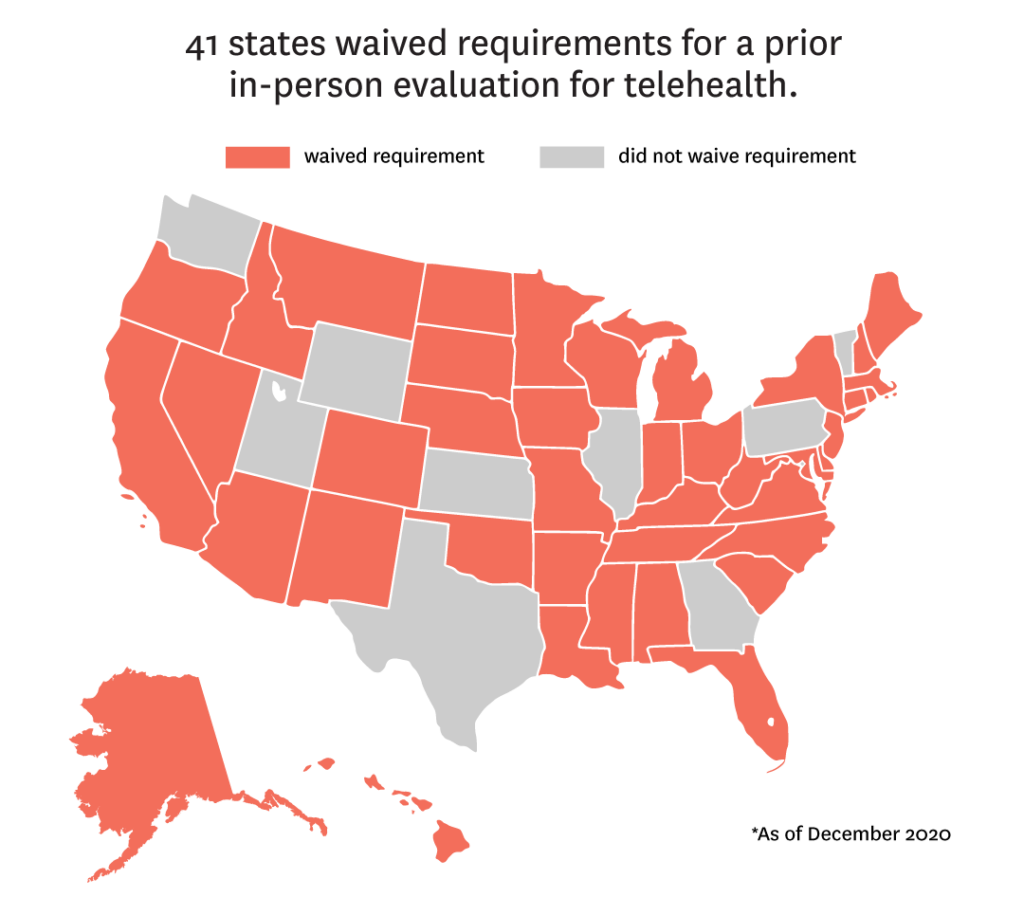

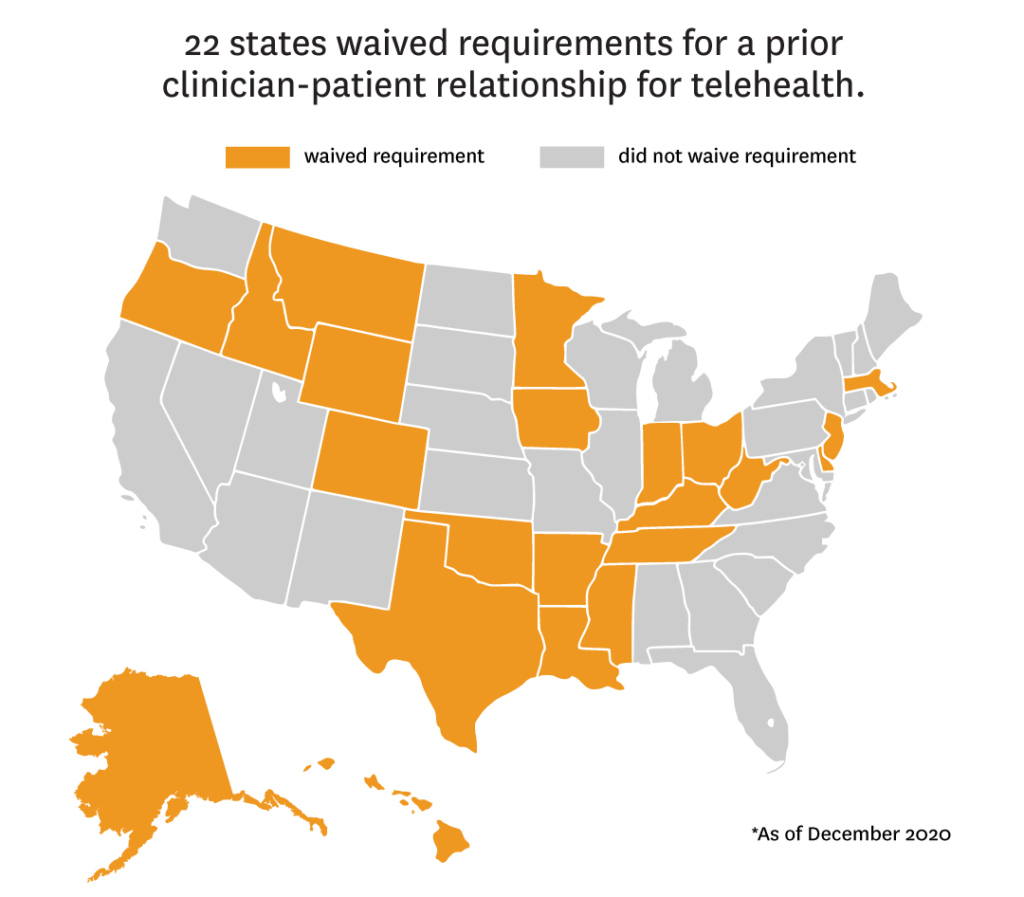

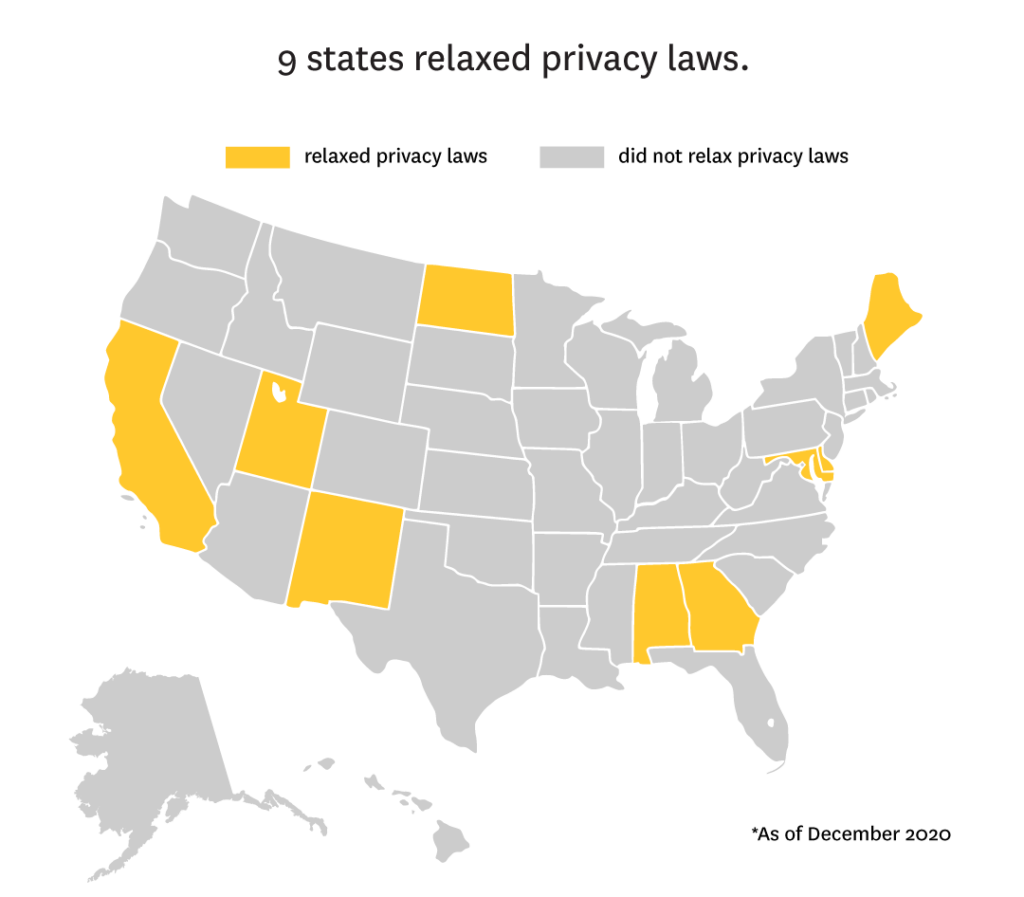

Furthermore, many states required pre-existing provider-patient relationships or in-person consultations before a telehealth visit could be conducted. Restrictive privacy laws also required direct consent to protect patient confidentiality.

As stay-at-home orders went into effect, state and federal governments took important steps to ensure treatment was accessible by expanding coverage, delivery, and payment of telehealth, loosening consent, privacy, and security requirements, loosening licensing requirements, and expanding initiation and dispensing of medication.

By September 2020, nearly all states enacted policies requiring benefit coverage for behavioral health via telehealth services and all states adopted at least one policy related to healthcare professional licensing permissions. In addition:

- 44 states expanded access to initiation and delivery of buprenorphine or methadone for OUD.

- 41 states waived requirements for a prior in-person evaluation.

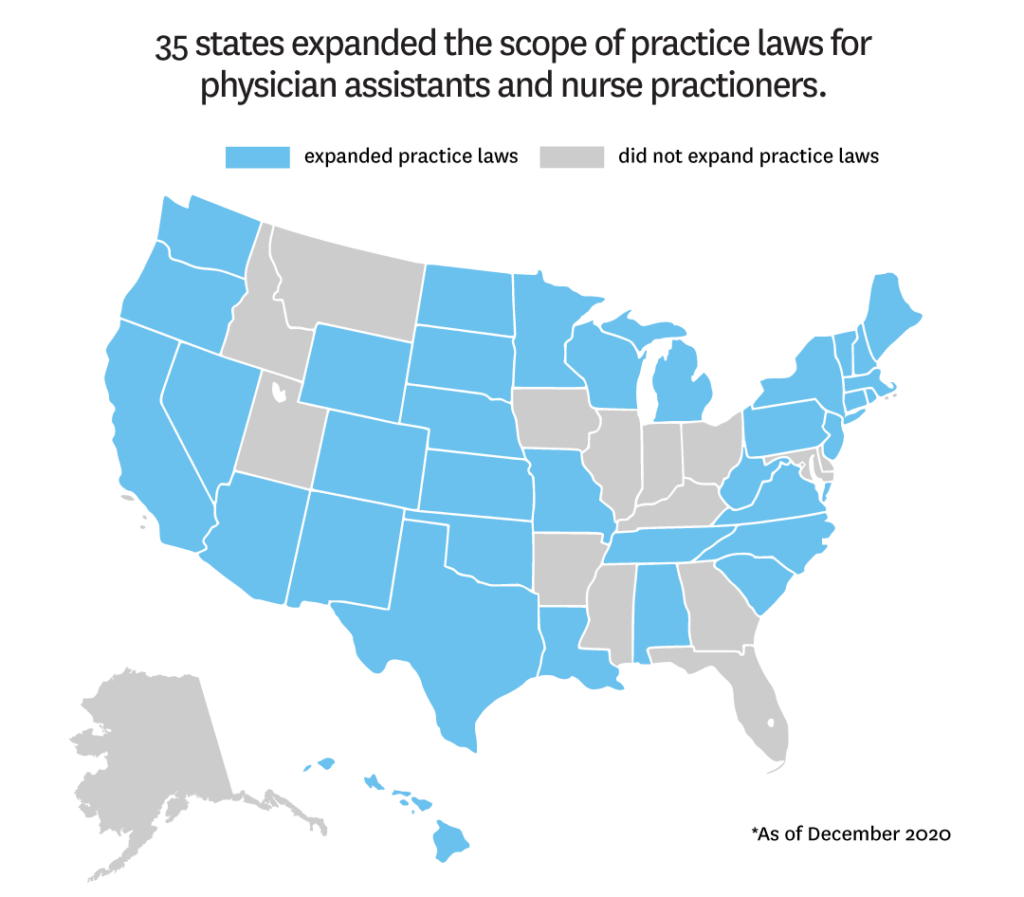

- 35 states expanded scope of practice laws for both physician assistants and nurse practitioners.

- 22 states waived requirements of a pre-existing provider-patient relationship.

- 9 states relaxed privacy laws.

No state implemented all the policies available to comprehensively expand access to OUD treatment during COVID-19.

“There were unprecedented policy changes due to COVID-19 that greatly expanded access for those with opioid addiction,” said Seema Pessar, co-author and Senior Health Policy Project Associate, USC Schaeffer Center. “We also saw states limit their response for the type of care patients could receive remotely.”

The impact of policy changes on opioid use

Early evidence from drug overdose data suggests opioid use increased during the pandemic. Barriers to accessing treatment may be the result of states not implementing all available policies. Interactions between policies impact the potential effectiveness of any one policy approach.

Furthermore, changes that were implemented are often temporary, which does little for patients in rural settings who could benefit from expanded access long-term.

“Patients in rural settings still live far away from treatment options and could benefit from telehealth and medication delivery,” Pacula said. “It is important we understand what policies can improve access so we can address immediate patient needs while also ensuring we’re prepared for future pandemics or natural disasters that may limit in-person treatment options.”