In a study published this week in Annals of Emergency Medicine, Sophie Terp and her colleagues report the first peer-reviewed longitudinal description of trends in enforcement of the Emergency Medical Treatment and Active Labor Act (EMTALA) in the last decade. Terp is an Assistant Professor of Clinical Emergency Medicine at the Keck School of Medicine at the University of Southern California and a Clinical Fellow at the Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics.

In 1986, EMTALA was passed by Congress in response to publicized incidents of inadequate, delayed or denied treatment of uninsured patients by emergency departments (ED). The intent of the law was to ensure access to emergency medical services and to prevent patient “dumping,” the practice of refusing or transferring financially disadvantaged patients without authorization or appropriate stabilization. EMTALA’s requirements include that all patients presenting to an ED receive timely and appropriate medical screening and to provide stabilization of identified emergent conditions, regardless of ability to pay.

Despite the importance of EMTALA in emergency health policy, there has been relatively little published on EMTALA enforcement activities.

EMTALA Citations were Found to be Rare at the ED Visit Level, But more Common at the Hospital Level

The researchers found 43 percent of hospitals with CMS provider agreements were investigated for an EMTALA violation and citations were issued at 27 percent of hospitals, between 2005 and 2014. Although EMTALA citations were rare on the ED-visit level, with 1.7 per million ED visits, citations were common at the facility level.

On average 9 percent of hospitals were investigated, and 4.3 percent were cited for EMTALA violation in a given year. Over the decade analyzed there was a 35 percent decline in EMTALA investigations as well as a 40 percent decrease in citations.

The Vast Majority of Hospitals Cited for EMTALA Violation Resolved Citations through Corrective Actions

The 10 regional Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) offices are charged with enforcing EMTALA including authorizing investigations, determining whether a violation occurred, and enforcing corrective actions when violations are identified. EMTALA investigations can be initiated by an individual or facility reporting an incident to CMS. Though hospitals and individual physicians face civil monetary penalties related to EMTALA violations, the crux of the enforcement mechanism is the risk of a termination of the CMS provider contract for failing to implement acceptable correct action plans following a violation.

During the period studied, the researchers found there were 4,772 authorized EMTALA investigations. Of those, 2,118 (44 percent) resulted in citation. Of hospitals cited for EMTALA deficiencies, only 12 were unable to resolve citations with corrective actions, resulting in termination of CMS provider agreements. Termination of CMS provider agreements resulted in at least temporary facility closure and/or downgrading of emergency services at three quarters of these facilities, likely because Medicare is the primary payer for almost half of inpatient hospital visits.

Most Citations Involved Medical Emergencies and EMTALA Deficiencies Related to Policies and Procedures

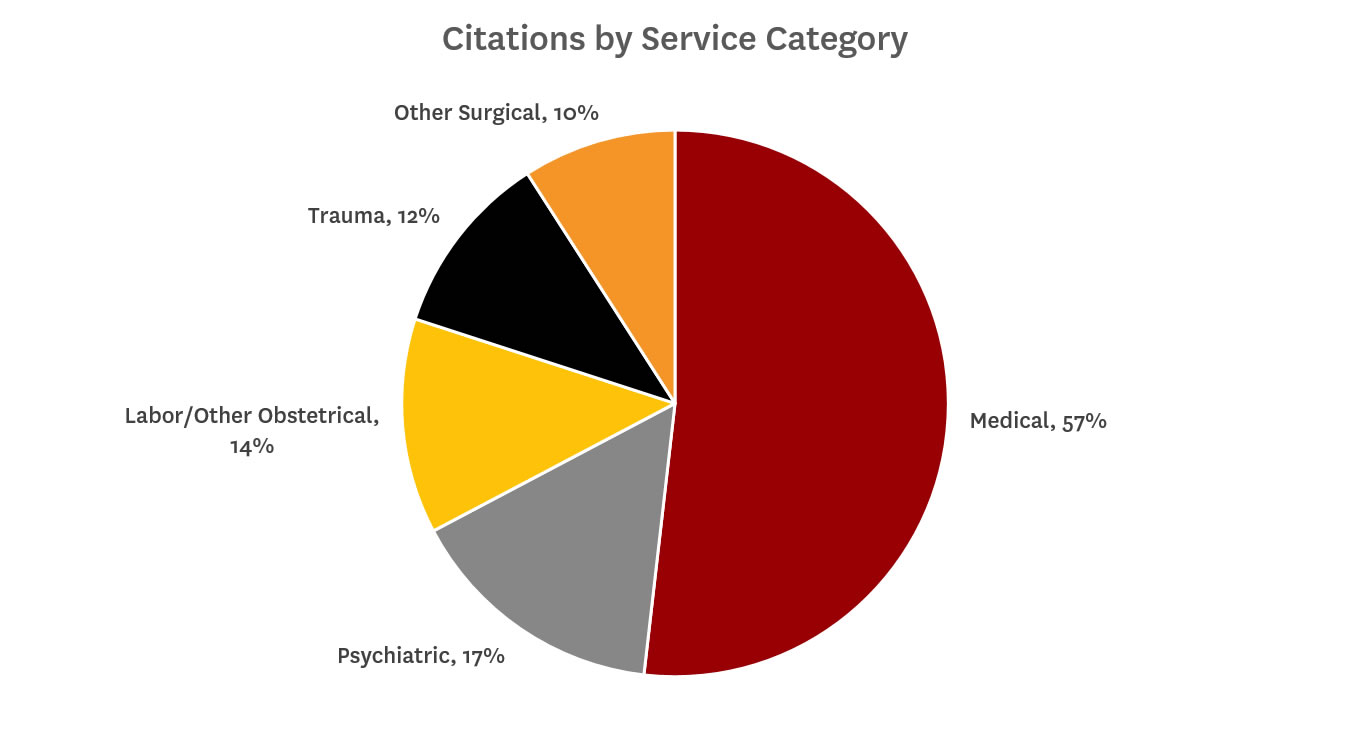

Terp and her colleagues analyzed the citations according to service category as well as the deficiency type. They found the majority of EMTALA citations involved medical emergencies (57 percent) followed by psychiatric emergencies (17 percent), labor and other obstetrical emergencies (14 percent), trauma (12 percent) and other surgical emergencies (10 percent).

In terms of deficiency types, 73 percent were cited for deficiencies related to policies and procedures; 55 percent were for failure to provide an appropriate medical screening examination; and 28 percent for failure to stabilize before transfer to another hospital. Hospitals were often cited for multiple deficiency types, including deficiencies unrelated to the specific complaint that triggered the investigation.

Implications of Study Findings on Quality and Access to Emergency Care

Though ED visits increased both in number and rate during the study period, authors identified a trend towards fewer EMTALA investigations and citations over the past decade. Between 2005 and 2014, EMTALA investigations declined by 35 percent, and citations declined by 40 percent. The proportion of investigations resulting in citations remained stable at 43 percent. Dr. Terp and colleagues theorize that the observed decline in EMTALA citations despite increasing numbers of ED visits could reflect improved hospital compliance with the statute, diminished enforcement efforts by CMS, or improvement to access to or quality of emergency care.

Many EMTALA citations involved administrative (non-direct patient care related) components of the law. Hospitals seem to be improving in some administrative categories of EMTALA deficiencies as citations for maintenance of a central log and on-call list decreased as a proportion of all EMTALA violations over time.

However, citations for clinical components of the law such as failure to provide appropriate medical screening exams and restricting transfer until a patient is stabilized increased as a proportion of all citations over the decade studied. According to Dr. Terp, “this finding in particular raises questions regarding whether EMTALA actually accomplished its original goals of reducing patient dumping or improving access to quality emergency care.”