Editor’s Note: This perspective was originally published in Health Affairs Forefront on March 4, 2024.

There is a growing mental health crisis among older adults: 20–30 percent of older adults older than the age of 65 report symptoms of anxiety or depression, and older adults exhibit the highest rate of suicidal ideation of any age group. However, only a fraction of affected Medicare beneficiaries receive treatment.

Recent work has uncovered critical issues with access to mental health providers in Medicare. Only 55 percent of mental health providers will see beneficiaries in traditional fee-for-service Medicare, the large government-run plan. Similarly, in the privately administered Medicare Advantage system, an estimated 65 percent of plans have narrow mental health provider networks, a rate that is substantially higher than in other privately managed insurance plans.

This lack of access to mental health providers for Medicare beneficiaries has been of increasing policy concern. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid (CMS), Senate Finance Committee, and Biden administration have each released policy proposals to address the topic in the past year. In this article, we provide economic intuition for the unique challenges to ensuring adequate mental health care access in Medicare and evaluate recent and proposed policies to alleviate the issue.

Provider participation in traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage

In both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, providers have the option to participate in the program or plan and provide care for plan enrollees at an agreed-upon price. For traditional Medicare, provider prices for each service are unilaterally set by CMS, and in response, providers can either opt in or opt out of participating in traditional Medicare. In Medicare Advantage, provider networks are formed through negotiations between insurers and providers, where a provider will only be in a Medicare Advantage plan’s network if both the provider and the insurer can agree on a negotiated price for the care enrollees will receive.

For both traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage, a provider is naturally more likely to participate if the provider is paid a higher price for providing care. However, provider decisions can also be affected by other factors. For instance, a provider’s total revenue is also impacted by patient volume, so providers are more likely to participate in networks of larger plans. Traditional Medicare, with its more than 30 million, mostly elderly enrollees, has historically been a major source of revenue for most providers and thus can typically achieve near-universal provider participation, even though it pays providers relatively low prices compared to commercial insurers. So why is Medicare participation so low among mental health providers?

Limits to Medicare’s negotiating power with mental health providers

Mental health care providers are subject to unique constraints and incentives, compared to other specialists. These differences emerge from mental health care’s historically marginalized status in the US insurance system, as well as the nature of mental health issues. We discuss these factors and provide economic intuition for how they impact mental health provider participation in Medicare below.

Mental health providers have alternative revenue streams apart from Medicare patients

While for most medical specialties, Medicare provides a large share of overall patient volume, many mental health providers have alternative sources of patients.

This is driven, in part, by the overall shortage of mental health providers in the United States. More than 160 million people in the United States live in Mental Health Provider Shortage Areas—regions where the current mental health workforce is insufficient to meet the needs of the population. This shortage not only makes it difficult for traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage to find sufficient numbers of mental health providers in many regions; it also means that many mental health providers can operate near or at capacity, even without Medicare beneficiaries.

A second factor that makes Medicare a less crucial source of revenue to mental health providers, compared to other specialists, is the age of the typical mental health care patient. While many physical conditions tend to manifest in old age, mental health issues often emerge earlier in life.

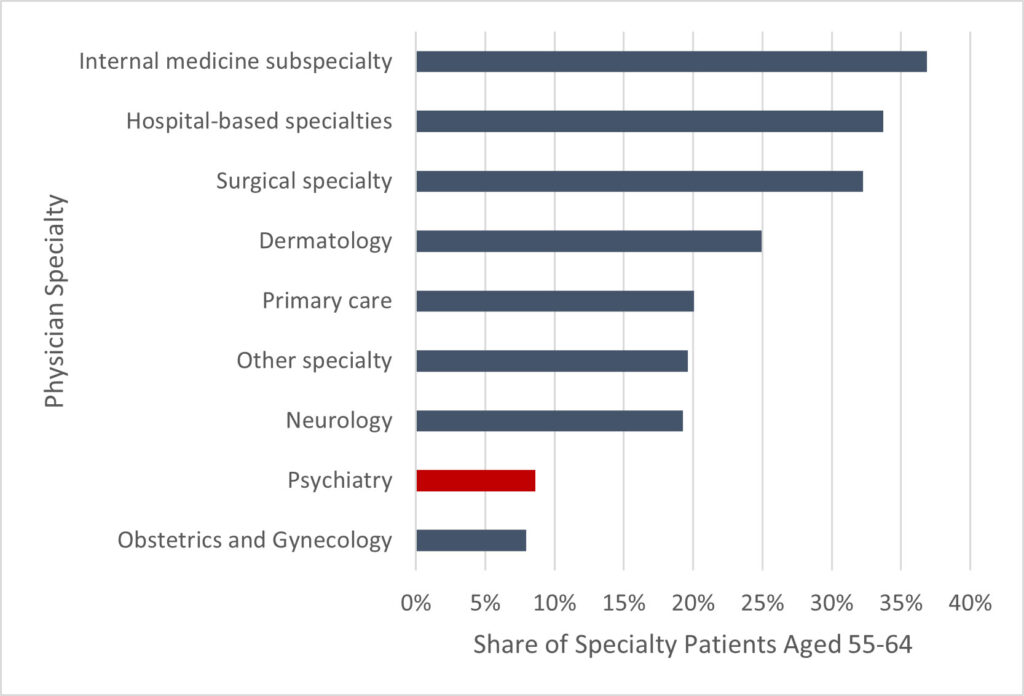

Exhibit 1 shows the average age of all non-Medicare patients seen in 2021 for each specialty. Compared to most other specialists, mental health providers see substantially younger patients, and per exhibit 2, see the fewest 55–64-year-olds. Hence, even absent Medicare’s barriers to access, older adults comprise a much smaller share of the potential mental health care patient population compared to other specialties.

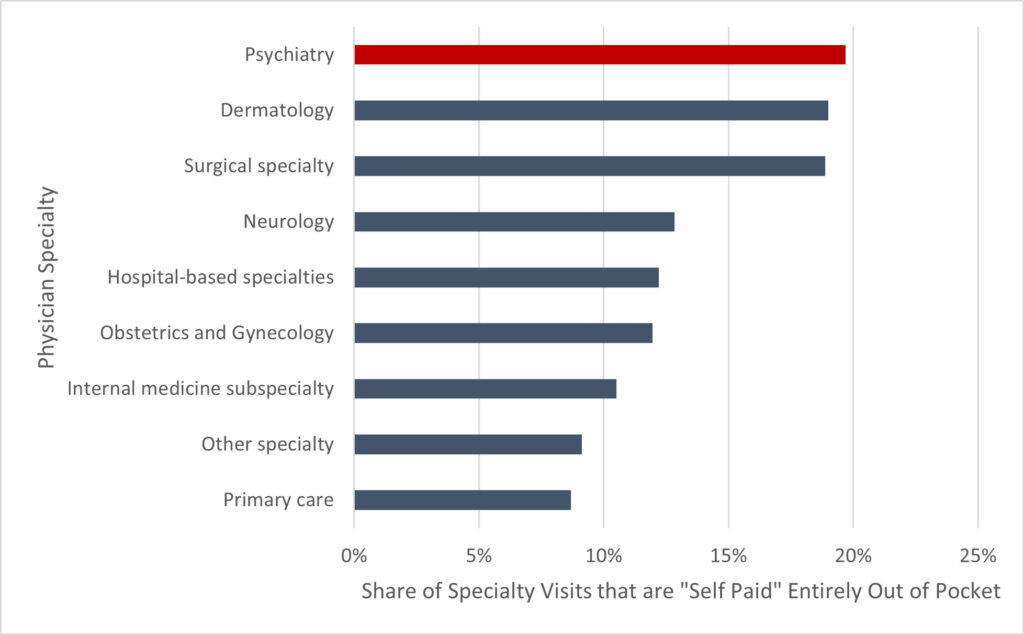

Finally, because of the historically marginalized status mental health has had in the broader US health care system, a large portion of mental health care providers now operate independently of formal insurance. As seen in exhibit 3, nearly 20 percent of outpatient mental health care visits were “self-pay” visits, which are visits entirely paid by the patient, compared to fewer than 9 percent among primary care physicians, for example. Likely because of the historically lacking coverage of mental health, today there is a sizable population of patients willing to pay entirely out of pocket for mental health care, thus providing an alternative source of revenue for mental health providers outside of Medicare.

In exhibits 1, 2, and 3, we use the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) data and employ MEPS-generated sampling weights to perform the analyses.

Exhibit 1: Average age of all non-Medicare patients seen by each specialty, 2021

Source: Authors’ analysis of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component data from 2021. Restricted to survey respondents younger than the age of 65 who are not enrolled in Medicare.

Exhibit 2: Share of total non-Medicare patients who are ages 55–64, by specialty, 2021

Source: Authors’ analysis of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component data from 2021. Restricted to survey respondents younger than the age of 65 who are not enrolled in Medicare.

Exhibit 3: Share of total non-Medicare patient visits that are paid entirely out of pocket, by specialty, 2021

Source: Authors’ analysis of Medical Expenditure Panel Survey Household Component data from 2021. Restricted to survey respondents younger than the age of 65 who are not enrolled in Medicare.

Medicare mental health patients may be particularly costly to care for

In certain instances, treating mental health in older adults may require greater expertise and some mental health providers may see caring for Medicare beneficiaries as more complex or costly. Relative to younger patients, older adults have higher rates of other mental or physical conditions that may complicate treatment. Age-related conditions, including vascular diseases, dementia, and diabetes are all risk factors for mental illness; however, they may also make diagnosis more challenging as providers have to discern signs of mental illness from symptoms of co-occurring conditions or side effects from medications. Subspecialty training in geriatric psychiatry focuses on treating mental health in older adults in this context; however, there is a very limited number of geriatric psychiatrists that have completed this training.

Furthermore, due to the high number of “self-pay” patients, receiving payment through insurance (including traditional Medicare and Medicare Advantage) may been seen as administratively burdensome to mental health providers. Reimbursement through insurance can take weeks, as opposed to cash payments that can be paid immediately for each visit. Medicare Advantage may introduce further administrative costs, as more than 80 percent of Medicare Advantage enrollees are enrolled in plans that have required prior authorization for mental health specialty services. Prior authorization is unpopular among physicians and overly restrictive policies may make mental health providers less likely to join Medicare Advantage.

Mental health providers are more likely to be independent of large health systems

Mental health providers not only have a lower incentive to participate in Medicare networks compared to other specialties, they also often have greater individual latitude in network negotiations. Often network participation decisions are made, not by individual physicians, but instead by hospital systems or medical groups, that bargain on behalf of all affiliated providers. However—by analyzing OneKey provider data on ownership status among active physicians—we show in exhibit 4, that 38 percent of psychiatrists operate independently of a larger corporate parent organization compared to 24 percent of primary care physicians. Thus, unlike other providers, whose network participation decisions are often influenced by the incentives of their corporate ownership, mental health providers can often make more tailored decisions.

Exhibit 4: Share of physicians operating independently, by specialty, 2021

Source: Authors’ analysis of 2021 OneKey data.

Evaluating policy options in light of Medicare’s negotiating position

These unique network formation dynamics for mental health providers shed light on recent and proposed policy efforts to expand access for Medicare beneficiaries.

Medicare prices

Given Medicare’s relatively weak negotiating position with mental health providers, it is perhaps less surprising that mental health care is one of the few types of care for which traditional Medicare pays higher prices than the price paid by the average commercial plan. Raising traditional Medicare prices for mental health would likely encourage more providers to participate in traditional Medicare. Furthermore, increased traditional Medicare prices would also likely result in increased prices for the same services in Medicare Advantage (and, therefore, increased participation among providers) as Medicare Advantage prices tend to track closely to traditional Medicare prices. In its 2024 Physician Fee Schedule Final Rule, CMS is increasing payments for psychotherapy for crisis services, although the effects of this policy remain to be seen.

Reducing administrative burdens

However, even if Medicare was willing to match self-pay patients in terms of service price, providers may still not be willing to take on patients if providing care will entail overly onerous administrative burden and long delays in payment. Another important policy to consider is reducing the relative administrative burden of providing mental health care for Medicare patients. The Mental Health Parity and Addiction Equity Act of 2008 requires, for example, that commercial insurers show that their prior authorization policies are no more restrictive for mental or behavioral health services compared to other services. However, no such policy exists for Medicare Advantage. Reducing administrative burdens introduced through prior authorization on specialty mental health services could improve participation among mental health providers.

Expanding eligibility for Medicare participation

CMS may also consider expanding the variety of providers that can provide mental health services. For example, further CMS policies to be in place in 2024 will allow additional providers—specifically Marriage and Family Therapists and Mental Health Counselors—to enroll as Medicare providers. This will grow the potential workforce of mental health providers that can contract with Medicare, although it may not impact the decisions of providers that already could participate and chose not to, such as psychiatrists. Relatedly, CMS has also proposed requiring Medicare Advantage plans cover an adequate number of outpatient behavioral health facilities, which would include these new provider types.

Other policy considerations

In addition to encouraging provider participation in Medicare, policy makers should also consider broader policies to facilitate access. This includes telehealth and cross-state licensing. As highlighted in a recent proposal by the Senate Finance Committee, facilitating greater telehealth access may help mitigate limited access for seniors, especially those in rural areas. Policy makers could also consider extending COVID-19-era policies that allowed mental health providers to practice across state lines.

Policy makers should also address institutional incentives in Medicare Advantage. Many of the unique challenges to mental health care access we have highlighted here have been exacerbated or directly caused by incentives among private insurers to discourage plan enrollment among beneficiaries with mental health needs. In addition to the policies highlighted above, policy makers may consider addressing structural contributors to the current status quo. For example, CMS should consider how it can address potentially perverse incentives for Medicare Advantage plans to exclude mental health providers from network.

Efforts could include ensuring that the risk-adjustment formula appropriately compensates plans for the average costs of mental health patients. Policy makers should also include more stringent benefit regulation and auditing of mental health networks. Addressing perverse incentives in Medicare Advantage could be an important first step to addressing similar, structural issues in the broader commercial market.

McCormack, G., Meiselbach , M., & Rohrer, J. (2024). Medicare’s mental health care problem. Health Affairs Forefront.

DOI: 10.1377/forefront.20240226.78751

Copyright © [2024] Health Affairs by Project HOPE – The People-to-People Health Foundation, Inc.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

You must be logged in to post a comment.