There’s a key but little-examined factor that likely helps explain Medicare Advantage’s enrollment surge in recent years: It’s much easier on beneficiaries’ wallets compared to traditional Medicare.

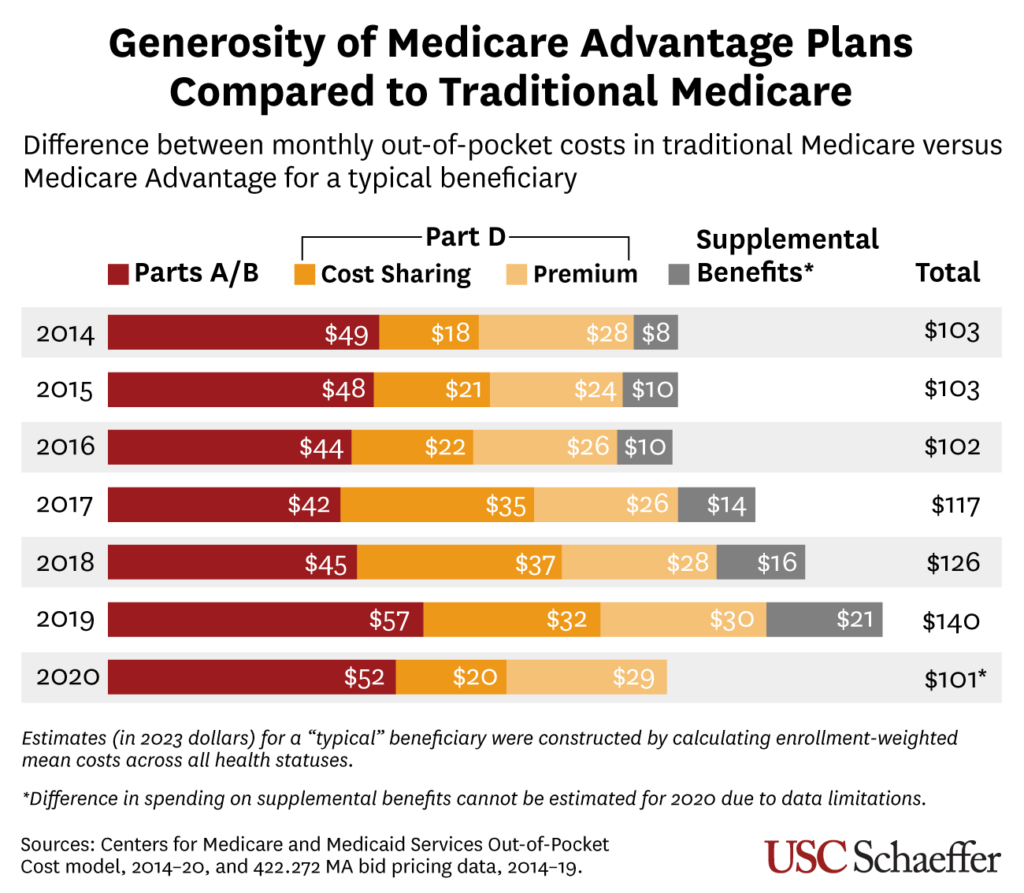

Expected monthly out-of-pocket costs were about 18-24% lower in Medicare Advantage than traditional Medicare for a typical enrollee from 2014 to 2019, according to a new Health Affairs study co-authored by Erin Trish, co-director of the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics.

More than half of Medicare enrollees now opt for Medicare Advantage plans administered by insurers, up from about one-third a decade ago. While this growth has brought increased scrutiny of Medicare Advantage’s higher government spending compared to traditional Medicare, there has been less focus on the difference in costs faced by beneficiaries themselves.

The comparatively lower out-of-pocket costs in Medicare Advantage represent “a huge financial benefit to seniors, especially if they have fixed incomes,” Trish said.

What Researchers Found

Comparing costs between the two programs has been difficult, since Medicare Advantage plans may offer supplemental benefits like vision and hearing, as well as reduced monthly premiums and cost-sharing. Trish and co-authors used Medicare data on expected out-of-pocket costs, which estimate a typical beneficiary’s monthly premiums and share of healthcare expenses, and publicly available data on Medicare Advantage bids.

For a typical enrollee, the average monthly out-of-pocket cost in 2019 was estimated at $440 in Medicare Advantage, substantially lower than the $579 in traditional fee-for-service Medicare. The gap in costs was even wider for beneficiaries in poor health.

In 2019, higher out-of-pocket costs for inpatient and outpatient coverage in traditional Medicare (Parts A and B, respectively) accounted for 41% of the difference in coverage generosity compared with Medicare Advantage. A nearly similar share (44%) was from Part D prescription drug coverage premiums and cost sharing. The value of supplemental benefits offered by Medicare Advantage accounted for just 15% of the difference, though that share had nearly doubled since 2014.

Policy Implications

Lower out-of-pocket costs in Medicare Advantage were likely attributable to three main factors, research suggests.

- To keep down costs, health plans use tools like pre-treatment approvals known as prior authorization and networks of selected providers. Medicare Advantage plans can use those savings to bid below a benchmark rate, resulting in rebates from the federal government that must be used to reduce cost sharing or premiums or supplemental benefits.

- Federal policy also sets those benchmark rates above traditional Medicare spending—for example, benchmarks averaged 9% more than traditional Medicare spending in 2023—which increases the size of these rebates.

- Plans can also receive higher payments from the government if they enroll sicker patients. Insurer practices leveraging this system are costing Medicare more than $80 billion in overpayments this year, driving conversations about potential reforms. While plans may use higher payments to increase profits, this study and past research suggests that higher Medicare Advantage payments are leading to more generous coverage for beneficiaries, researchers said.

“There’s a lot of attention on Medicare Advantage plans being overpaid, but what’s sometimes left out of that discussion is how the plans use that money,” said Trish, who is also an associate professor of pharmaceutical and health economics at the USC Mann School of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences. “Plans use much of it to offset costs that beneficiaries would otherwise pay. For example, plans are paying for beneficiaries’ Part D coverage and eliminating their exposure to high hospital and physician out-of-pocket costs.”

Trish noted a large part of Medicare Advantage enrollment growth in recent years has come from lower-middle- and middle-income beneficiaries, who may be especially sensitive to cost. While out-of-pocket costs may be a key factor in considering Medicare Advantage, beneficiaries may also weigh tradeoffs like limited provider options, the potential for care delays or denials through prior authorization, and whether they would be able to purchase affordable supplemental Medigap coverage if they wanted to disenroll from Medicare Advantage in the future.

Trish said the new study isn’t an endorsement of higher Medicare Advantage spending levels, but the findings suggest a challenging tradeoff for policymakers—reducing program payments to traditional Medicare levels could mean higher out-of-pocket costs for beneficiaries.

“You now have a lot of beneficiaries enrolled in the program who are used to getting very generous benefits, and it can be hard to take those away,” Trish said.

About the Study

Other co-authors are Benedic Ippolito, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, and Boris Vabson, a Harvard Medical School researcher and nonresident senior scholar at USC Schaeffer. Trish was supported by a grant from the Commonwealth Fund.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

You must be logged in to post a comment.