Fixing a Broken Foundation

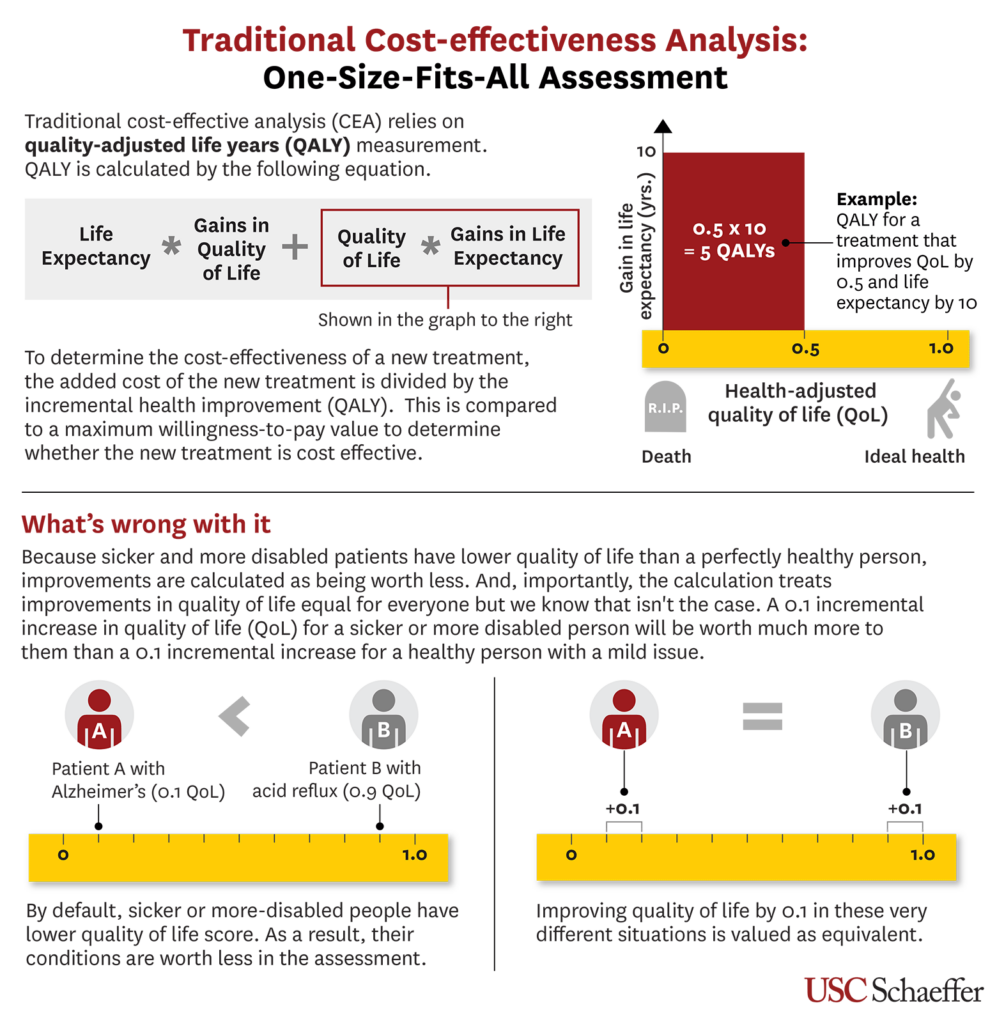

Today’s methods for quantifying the value of healthcare interventions are rooted in traditional cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA). These methods are inadequate for measuring the actual value of treating severe diseases because they rely on quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), which attempt to measure both the length and quality of life. One QALY is in principle equivalent to one year of perfect health. But QALYs still fall short of measuring the actual value because they:

- Fail to account for the target patient population’s perspectives, priorities or values.

- Discriminate against patients who are older, disabled or have complex conditions. Traditional CEA assumes that QALYs are always worth the same, regardless of context or circumstances.

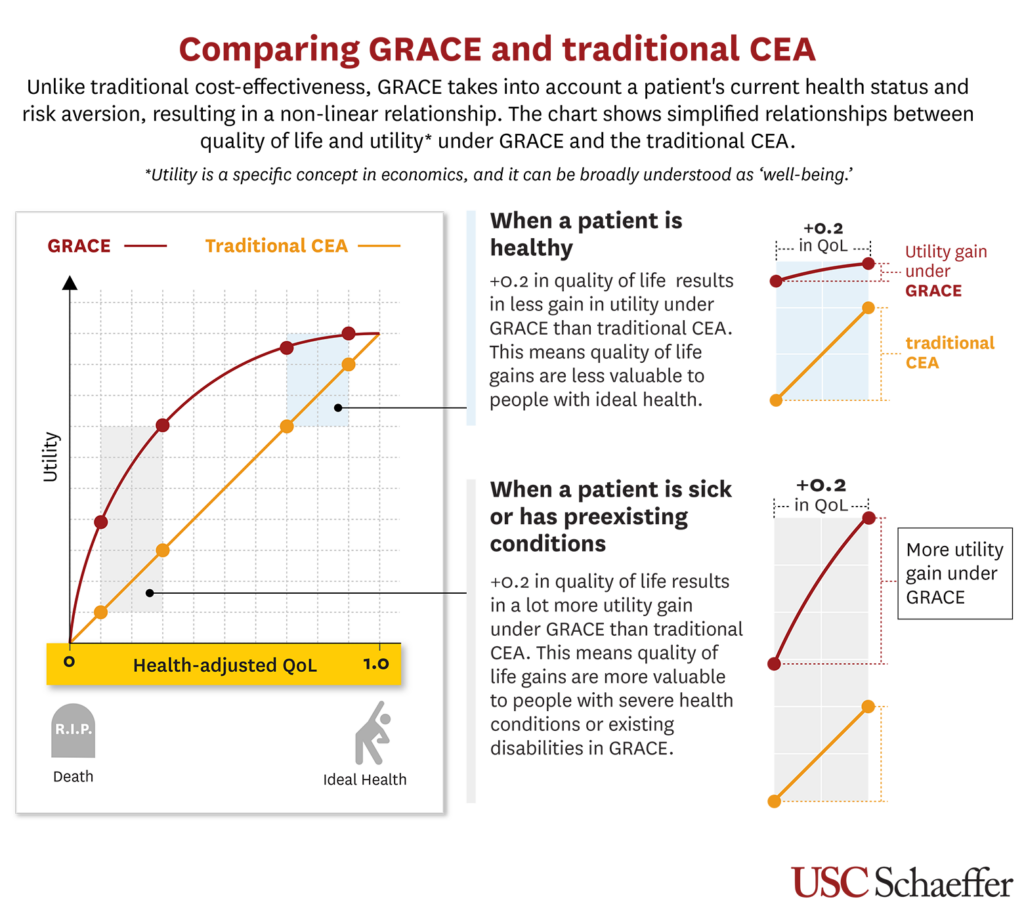

USC Schaeffer Center Director of Research Darius Lakdawalla and Nonresident Senior Fellow Charles Phelps have developed a new method: Generalized Risk Adjusted Cost-Effectiveness (GRACE) – a patient-centric model providing a more effective means of calculating the value of care. Based on well-established and quantifiable economic concepts, GRACE adheres to an economic principle that the current CEA methodology fails to consider—goods are more valuable when they are scarcer. So just as $5,000 means less to a millionaire than to the average person, a given health improvement offers greater value for people with disabilities or severe diseases than to those in better health.

By recognizing that health is worth more to those who have less, GRACE provides a more equitable approach to value assessment and healthcare investments. This avoids discriminating against people with disabilities or other adverse health conditions. Current U.S. law prohibits the use of economic methodologies that discriminate against the aged, the terminally ill and the disabled. GRACE comports with the law and promotes a more equitable distribution of resources across sicker and healthier groups.

Features of GRACE

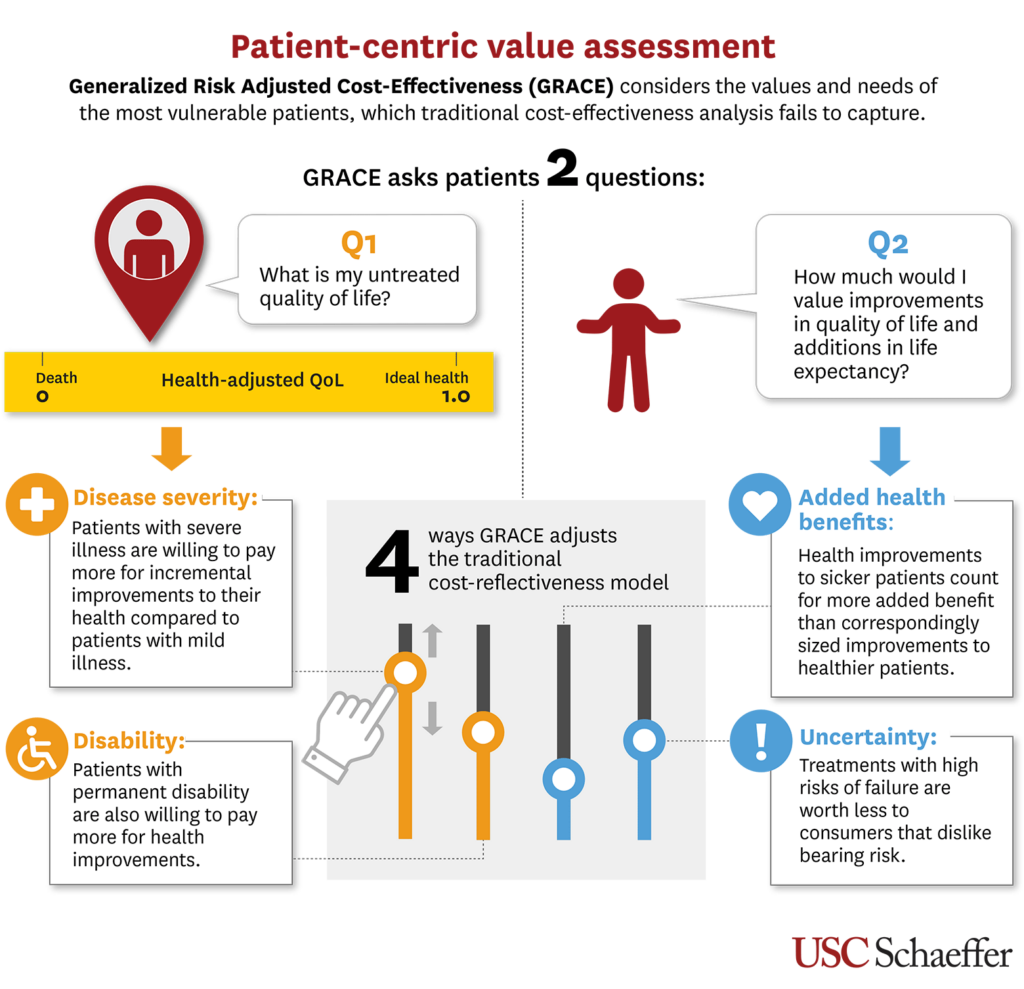

Fundamentally, all cost-effectiveness analysis starts by asking patients two questions:

- What is my untreated quality of life?

- How much would I value improvements in quality of life and additions in life expectancy?

The standard CEA model calculates the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio—added cost (compared to the next-best alternative) divided by added health benefits—and then compares this ratio to the willingness to pay (WTP) for health improvement. However, this approach fails to consider the impact a patient’s current health status has on their WTP for health improvement (question number one). In contrast, GRACE considers the values and needs of the most vulnerable patients, and how they might differ from those in better health circumstances.

It does this by recognizing the inherent relationship between the quality of life the patient starts with (question number one) and the value placed on health improvements (question number two). This recognition allows the value of health improvements to vary with the patient’s context and circumstances.

To take it a step further, GRACE considers a patient’s current health status and risk aversion. It fundamentally incorporates patient preferences based on the responses to the two questions in four concrete ways, thereby aligning WTP with the values and priorities of real patients:

1. What is my untreated quality of life?

- Disease severity: Through patient survey data, we know that WTP for health improvements increases when treating more severe illnesses and falls when treating milder illnesses.

- Disability: WTP for health improvement rises for patients with permanent disabilities also.

As a result, using GRACE results in WTP and cost-effectiveness thresholds that become more generous for severe illnesses and less generous for milder conditions – potentially differing up to a factor of 10 from lowest to highest severity. This aligns the value of medical technology with what patients care about, focusing investments where patients benefit most. In short, patient context matters, and GRACE recognizes this.

2. How much would I value improvements in quality of life and additions in life expectancy?

- Added health benefits: Health improvements to sicker patients count for more added benefit than correspondingly sized improvements to healthier patients.

- Uncertainty: Treatments with high risks of failure are worth less to consumers who dislike bearing risk.

GRACE incorporates the effects of uncertain health outcomes into assessments of new treatments and technologies. Reductions in outcome uncertainty provide value to risk-averse individuals, and value assessments should include such effects – especially in contexts with modest incremental average health gains.

The result is a non-linear relationship between health-adjusted quality of life and value.

Formulating a Patient-Centered, Healthier Future

GRACE could push healthcare decisions toward more patient-centered outcomes in four key areas:

- Altering the coverage determinations of health plans—whether private policies or public-sector programs. Full adoption of GRACE could increase reimbursement for therapies that treat more severe diseases and away from milder conditions.

- Reforming prior authorization and other formulary restriction rules. Insurance companies regularly exclude coverage of treatments that are new or don’t have extensive outcomes data yet, which will most often affect those with the lowest health status. GRACE could lead to greater access to such interventions for severely sick or disabled persons because the evidence on patient preferences implies that even a modest chance of benefit provides substantial value to patients in such circumstances.

- Assisting in shared decision-making so that patients, clinicians and health systems can identify the highest-value therapies for particular patients. Transparency in value assessment and price will help inform all stakeholders in the system about the choices that are being made.

- Increase investment in therapies that help people with more severe illness, as the adoption of GRACE widens to better reward the research and development of innovative drugs, devices and procedures that treat those populations.

GRACE appropriately aligns value assessment with the preferences of real human consumers. It forestalls the need for increasingly prevalent, ad hoc, and unfounded exceptions to CEA for end-of-life care, rare diseases and such severe conditions as cancer. The GRACE model also goes further than any current economic approach to allow for patients’ preferences to be considered at both the individual and population levels. Importantly, any source of patient preference survey data can be used in the GRACE model. If used widely, GRACE could push healthcare systems towards more patient-centered outcomes.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

Related Work

Journal Articles

A principled approach to non‑discrimination in cost‑effectiveness

February 27, 2024 | By Darius Lakdawalla, PhD and Jason Doctor, PhD | The European Journal of Health Economics

Risk Preferences Over Health: Empirical Estimates and Implications for Medical Decision-Making

March 1, 2024 | By Karen Mulligan, PhD, Jason Doctor, PhD, Charles E. Phelps, PhD, Darius Lakdawalla, PhD and Drishti Baid | Journal of Health Economics

Methods to Adjust Willingness-to-Pay Measures for Severity of Illness

February 14, 2023 | By Charles E. Phelps, PhD and Darius Lakdawalla, PhD | Value in Health

Generalized Risk-Adjusted Cost-Effectiveness (GRACE): Ensuring Patient-Centered Outcomes in Healthcare Decision Making

September 1, 2021 | By Darius Lakdawalla, PhD and Charles E. Phelps, PhD | Value & Outcomes Spotlight

A Guide to Extending and Implementing Generalized Risk‑Adjusted Cost‑Effectiveness

September 8, 2021 | By Darius Lakdawalla, PhD and Charles E. Phelps, PhD | The European Journal of Health Economics

Health Technology Assessment with Diminishing Returns to Health: The Generalized Risk-Adjusted Cost-Effectiveness (GRACE) Approach

January 12, 2021 | By Darius Lakdawalla, PhD and Charles E. Phelps, PhD | Value in Health

Health technology assessment with risk aversion in health

June 6, 2020 | By Darius Lakdawalla, PhD and Charles E. Phelps, PhD | Journal of Health Economics

You must be logged in to post a comment.