Cal State Dominguez Hills student Alejandro Campos Robledo has been having panic attacks since he learned he could lose his DACA status. Robledo often works through the stress with prayer and meditation. The mural behind him depicts the cultural diversity of the U.S. He fears he may get deported and have to leave his 11-year-old daughter behind. (Photo by Bill Alkofer, Contributing Photographer)

Editor’s note: This story was first published in the The Orange County Register on Nov. 15, 2019 and written by Claudia Boyd-Barrett.

Tomasa Martinez sat with a dozen other somber-faced mothers, trying not to weep.

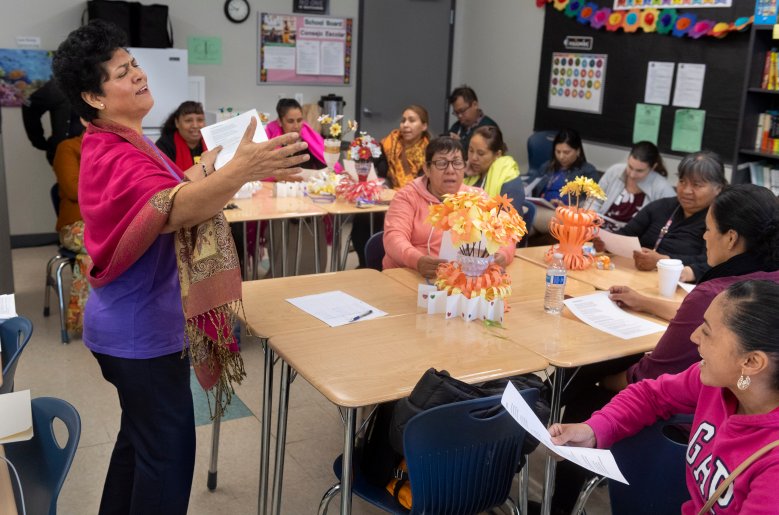

The women were in a classroom at Alliance College-Ready Middle Academy in East Los Angeles, as part of a weekly class sponsored by the Los Angeles County Department of Mental Health.

Today’s topic: “Traumatic stress caused by immigration laws.”

“My little girl, she watches the TV and she says, ‘Mommy, I don’t want to go to school,’” Martinez told other mothers in Spanish.

Martinez started to sob when she described the anxieties gripping her 11-year-old daughter, Emily. As the girl hears story after story about immigrants held in cages and of families separated — and of other kids in her neighborhood who end up alone when their parents are deported — Martinez said her daughter expresses her fear plainly:

“I don’t want to come home and you not be here, or for Daddy not to come home from work.”

For the woman leading the discussion, Elsa Barajas, a Los Angeles County community health educator — or “promotora” in Spanish — the situation is all too familiar.

Within Latino communities of Southern California, mental health workers say, the psychological and emotional woes that come from extreme, unrelenting stress are nothing short of epidemic.

Triggers everywhere

Hostile federal immigration policies, stepped up arrests by Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), anti-immigrant rhetoric from President Donald Trump and his supporters, mounting racial discrimination and hate crimes — all are touching nerves within the Latino community.

And this month, as the Supreme Court hears arguments that could end in the demise of DACA, the program known as Deferred Action on Childhood Arrivals that protects about 700,000 young Latinos from deportation, that stress is only ratcheting up.

As a result, experts say many Latinos — from recent immigrants to long-time residents and citizens, like the Martinez family — are coping with a growing cycle of fear and uncertainty. That tension, in turn, is manifesting as everything from unhealthy levels of depression to toxic stress to PTSD.

If the outbreak has a cause, it is the new politics of immigration.

In a 2018 study by The Children’s Partnership and California Immigrant Policy Center, more than half of immigrant parents surveyed said they felt stress, fear, frustration, anxiety and sadness more often than they did before the 2016 election. Almost two thirds of those parents said their children worried about their own safety and the well being of their family, and more than half said their kids are increasingly fearful and anxious.

A study published in July, by the American Medical Association’s JAMA Network Open, reported that since the 2016 election there’s been an unexpected increase in preterm births among Latina women. Preterm birth rates are known to rise among populations under increased stress

“There’s so much fear about getting deported, or having a family member get deported. People are afraid to go to work. Children are afraid of losing their parents… There’s a lot of grief, a lot of loss,” said Ana Suarez, director of the Los Angeles County’s Mental Health Promotores program.

The problem isn’t limited to the immigrant community. Latinos who are U.S. citizens and legal residents also are experiencing more stress-related problems. Millions of Americans live in mixed-status households, where at least one member is undocumented or their legal status is threatened by Trump policies, such as the move to repeal DACA..

Others fear or experience blatant discrimination, a known trigger for mental health problems.

A recent study of nearly 400 U.S.-born Latino teens with at least one immigrant parent found they had higher-than-normal levels of anxiety, higher blood pressure and more trouble sleeping. A Pew Research Center study this year found more than half of Hispanic adults report experiencing discrimination because of their race or ethnicity. Another study found greater fear, anxiety and anger among young Latinos living in Southern California.

In the case of the Martinez family, Emily has reverted to sleeping with a light on. She often wakes up, crying, convinced that at any moment ICE agents might barge into her home to take her and her parents away.

Another mom at the middle school workshop, Mary Feliciano of Boyle Heights, described how her older daughter, a citizen born in the U.S., was mortified when a man at a train station called her “a stupid Mexican” after she asked him for directions. Feliciano tried to reassure her daughter, but she also felt devastated.

“Can you imagine how you would feel if a child of yours is treated that way?” she said in Spanish. “It’s as if the very fibers of your being have been touched.”

Barajas, the mental health educator, said anti-immigrant rhetoric can make people feel like they’re under attack and that, in turn, can lead to lower self-esteem and a general feeling of being unsafe. In her workshops, Barajas encourages her students to embrace their cultural heritage, recognize their contributions to the United States, and be a source of strength in their families and communities.

“We’re beautiful,” she told the mothers.

“Society wants to take us down, wear down our batteries. But we won’t let that happen.”

New feeling

Until Sept. 5, 2017, Alejandro Campos Robledo had never heard of a panic attack.

But as he watched the news that day, and saw then Attorney General Jeff Sessions announce the Trump administration’s plan to end DACA, Campos Robledo felt an unfamiliar tightening in his chest and shortness of breath.

“I’d never felt anything like that before,” he recalled. “I thought, ‘What’s going on?’”

The program the Trump administration wants to end, DACA, was — and is — a key force in his life.

Now 35, of Whittier, Campos Robledo was brought to this country from Mexico at age 8, so he’s not a legal citizen. But under the protection of DACA, which was enacted in 2012, he’s been able to pursue his dream of becoming an occupational therapist. He recently graduated from Cal State Dominguez Hills with a bachelors in physical education, and is working toward a Masters degree.

But with DACA still hanging in the balance the stress hasn’t really faded. In the months after the announcement, Campos Robledo had several more panic attacks. To this day, he fears he could be deported at any moment.

What’s more, he notes, he’s not the only DACA recipient who feels this way.

“I see a lot of friends that are worse, that have dropped out of school, that cry every day,” Campos Robledo said. “They don’t go out as much anymore. There are a lot of people I know who are DACA kids and they’re literally hiding. They don’t want texts, they’re not on social media anymore.”

Other young Latinos — including citizens born in the country and others, like Campos Robledo, who only know this country as home — are experiencing unprecedented levels of distress.

Rosa Chavez, a counselor at Ponderosa Elementary in Anaheim, where around 90 percent of students are Latino, has seen a marked increase in children with anxiety over the past three years. She said she sees it in a variety of ways — kids acting out in class, fighting, or simply withdrawing from friends and teachers.

“Some kids have heard of neighbors being deported. That always brings fear, not knowing what’s happening, who’s next,” she said. “They don’t quite understand what all of this means.”

Josefina Jimenez, a promotora with the Santa Ana-based nonprofit Latino Health Access, which helps families facing immigration and other crises, said she also is seeing more traumatized children.

In just the past month, Jimenez said, she’s helped a family get counseling for a 12-year-old girl who became inconsolable after her older brother was detained for immigration violations. The girl doesn’t want to go to school and is terrified her parents will be arrested too.

Another case involved two elementary school children whose undocumented father was detained for driving without a license. The man, who lives in Santa Ana, was released after two days. But while he was held his children were distraught, Jimenez said, believing he was about to be sent away.

“You are moved so much,” she said in Spanish. “I’m a mom, I have children. Luckily, my immigration situation is OK. But it hurts me that a child… has to suffer from all this uncertainty.”

In San Bernardino, Jennaya Dunlap also helps families navigate immigration issues in her work for the Inland Empire Coalition for Immigrant Justice. She said she’s seen children stop eating, lock themselves in their rooms, and start failing at school after a parent was detained or deported. In one case, she said, a girl around 6 was diagnosed with PTSD.

Era of fear

Petra Alexander, director of the Office of Hispanic Affairs for the Diocese of San Bernardino, said she’s also noticed an increase in mental distress among immigrant congregants — specifically since the 2016 election.

“For so many immigrants there is a “before and after” in the state of their emotional, physical, and mental health due to the influences of the current presidential administration,” she wrote via email. “We have witnessed that emotions are anxiety and stress. Persons who do not have documentation or who are in the process of filing are constantly apprehensive as a direct result of the rhetoric of the times which includes rejection and bullying.”

At Community Congregational United Church of Christ, a progressive church in Los Alamitos, Pastor Sam Pullen said some of his Latino congregants have lived and worked in the city for decades and, until recently, felt at ease.

Now, Pullen added, under the Trump administration — and since Los Alamitos made national headlines by exempting itself from California’s sanctuary law, which limits how police work with federal immigration officials — some long-time residents feel like they and their children are no longer welcome.

The pastor said he knows of Latinos who have sought therapy to cope with anxiety. Parents, he added, have talked to him about increased racial bullying at schools. Pullen himself sought therapy after he received backlash for speaking out in defense of Latinos in his town.

“There’s just a sense of the community not being as safe as people thought it was,” he said.

For Martinez, the mother who participated in the mental health workshops in East Los Angeles, a few new strategies have proved effective in managing her daughter’s anxiety and her own feelings of despair.

She used to cry along with her daughter when the girl grew upset. Now, Martinez said, she’s learned to remain calm, to listen, and to patiently explain the family’s situation in terms that her daughter can understand. She also now limits her daughter’s consumption of news. The girl, she said, is doing better.

So is Martinez.

“I’m calmer,” she said. “Things still affect me, of course, but not as much as before when I didn’t know what to do… Now, I know I’m not alone.”

But health experts worry that many other Latinos aren’t getting the information and support they need to manage their stress before it becomes unhealthy. This could have long-term consequences for families and society as a whole, said Carolina Valle, policy manager with the health advocacy group California Pan-Ethnic Health Network.

“Untreated mental health issues have intergenerational impacts on families,” she said.

“We’re going to see…greater anxiety, greater depression, greater isolation.”

Claudia Boyd-Barrett writes for the Center for Health Reporting at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. Reporting was supported by a grant from the California Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission.

You must be logged in to post a comment.