Last winter, public officials had to decide which groups would receive priority for the limited quantities of newly approved COVID-19 vaccines. A new USC Schaeffer Center study finds that how vaccines are allocated may contribute to vaccine hesitant individuals later refusing the vaccine when it is made available to them.

“Disinterest in getting the vaccine increased among all groups when they were overlooked and had to wait for a vaccine,” says Wändi Bruine de Bruin, co-director of the Behavioral Sciences Program at the USC Schaeffer Center. “Even among people who initially wanted the vaccine, a surprising share — 16% — said they no longer wanted it after they were passed over. Public health officials should keep this dynamic in mind when developing plans in the future- whether it is the rollout of booster shots or other vaccinations.”

The study, published in the Journal of Risk Research, drew off consumer research that suggests when people are overlooked during the initial allocation of a product, they will lose interest. While COVID-19 vaccines are now widely available in the U.S., certain groups had to wait. In countries where supplies are limited, people are still waiting.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

“We can’t wind back the clock, but we can learn from what happened. We now know that when vaccine supply is limited, we need to fairly and simply allocate early doses. Otherwise, we may encourage future vaccine refusal” says Dana Goldman, Schaeffer Center co-director and dean of the USC Sol Price School of Public Policy.

Once people feel overlooked, they may no longer want to get vaccinated

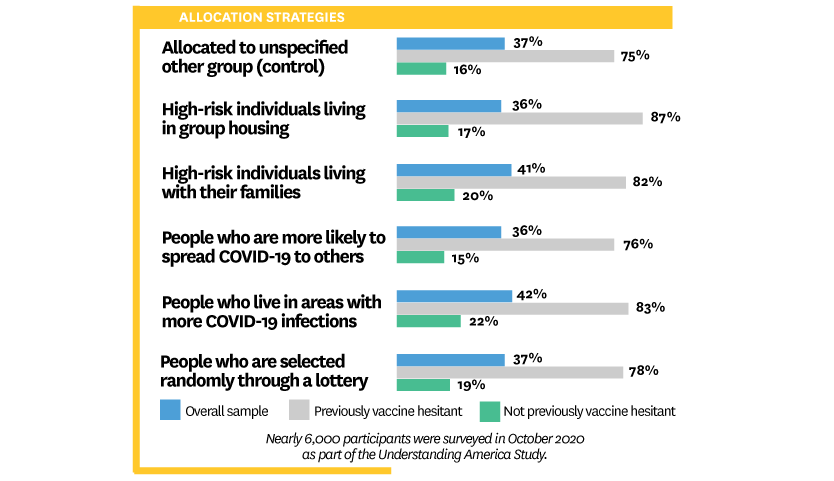

The researchers surveyed nearly 6,000 individuals from the Understanding America Study in October 2020. Participants were asked who they thought should be vaccinated next after healthcare workers and nursing home workers. Participants could choose from five different groups:

- High-risk individuals in group housing

- High-risk individuals living with their families

- People more likely to spread COVID-19 to others

- People who live in areas with more COVID-19 infections

- Participants who are selected randomly through a lottery

After healthcare workers, almost half of participants preferred vaccines go to high-risk individuals living in group-settings.

The researchers then looked at what happened if a vaccine strategy initially overlooked participants and required them to wait. They found 37% of participants indicated they would refuse the vaccine if they felt they had initially been overlooked for any reason. When overlooked because the allocation strategy prioritized people in areas with higher rates of COVID-19 – policies that were implemented in many areas – reported refusal to get the vaccine rose to 42%.

“Being overlooked by the way vaccines are being handed out has consequences,” explains Aulona Ulqinaku, assistant professor of marketing at the University of Leeds. “In this case, it may explain why some people, even those who do not self-identify as vaccine hesitant, are uninterested in getting the vaccine even when it is widely available.”

Allocation strategies affect vaccine hesitant and non-hesitant groups

Overall, 30% of participants indicated they were already hesitant to take the vaccine. Yet among those who indicated they were not vaccine hesitant, 16% said that they would no longer want the vaccine if they were overlooked for any reason. Depending on the reason for being overlooked, this percentage varied 15% to 22%.

“In countries where vaccine quantity is still limited, public officials should consider how both hesitant and non-hesitant groups may respond to different allocation strategies,” Bruine de Bruin says. “Implementation strategies should be transparent and ready to manage the expectations of groups who may later respond by refusing the vaccine.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.