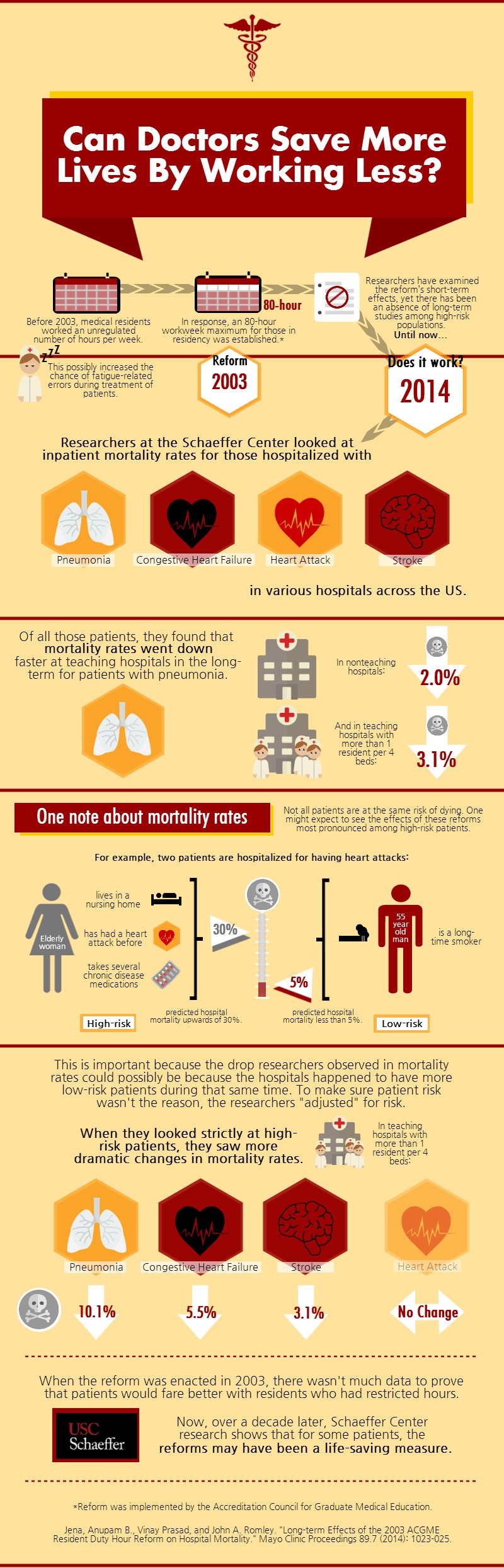

Before 2003, medical residents worked an unregulated number of hours per week. This possibly increased the chance of fatigue-related errors during treatment of patients. In response, an 80-hour workweek maximum for those in residency was established by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Researchers have examined the reform’s short-term effects, yet until now, there has been an absence of long-term studies among high-risk populations.

Schaeffer Center researcher John Romley co-authored the study that looked at inpatient mortality rates for those hospitalized with pneumonia, congestive heart failure, heart attack, and stroke in various hospitals across the US. Of all those patients, they found that mortality rates went down faster at teaching hospitals in the long-term for patients with pneumonia. In nonteaching hospitals, mortality rates for patients with this condition decreased by 2.0% and in teaching hospitals with more than 1 resident per 4 beds, mortality rates decreased by 3.1%.

However, there is one thing to note about mortality rates. Not all patients are at the same risk of dying; one might expect to see the effects of these reforms most pronounced among high-risk patients. For example, two patients are hospitalized for having heart attacks. A high-risk patient would be an elderly woman who lives in a nursing home, has had a heart attack before, and takes several chronic disease medications, with a predicted hospital mortality rate upwards of 30%. A low-risk patient would be an otherwise healthy 55-year-old man who is a long-time smoker with a predicted hospital mortality rate of less than 5%.

This is important because the drop researchers observed in mortality rates could possibly be because the hospitals happened to have more low-risk patients during that same time. To make sure patient risk wasn’t the reason, the researchers “adjusted” for risk. When they looked strictly at high-risk patients, they saw more dramatic changes in mortality rates. In teaching hospitals with more than 1 resident per 4 beds mortality rates for patients with pneumonia decreased 10.1%, for patients with congestive heart failure decreased 5.5%, and for patients with stroke decreased 3.1%.

When the reform was enacted in 2003, there wasn’t much data to prove that patients would fare better with residents who had restricted hours. Now, over a decade later, Schaeffer Center research shows that for some patients, the reforms may have been a life-saving measure.

Study citation:

Jena, Anupam B., Vinay Prasad, and John A. Romley. “Long-term Effects of the 2003 ACGME Resident Duty Hour Reform on Hospital Mortality.” Mayo Clinic Proceedings 89.7 (2014): 1023-025.