The FDA’s announcement that it will decide by March 2021 whether to allow clinical use of the drug aducanumab to treat Alzheimer’s disease signals a potential breakthrough in the long battle against the debilitating disease, said Paul Aisen, founding director of the USC Alzheimer’s Therapeutic Research Institute (ATRI).

Aisen was lead speaker at a September 1 webinar hosted by the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy. The session examined hopeful signs in clinical development and policy to make Alzheimer’s disease treatments and diagnostics readily available.

Aisen was introduced by Leonard Schaeffer, a trustee at the Brookings Institution and at USC. Schaeffer noted that Alzheimer’s is the only disease in the top 10 leading causes of death in the U.S. that can’t be prevented, delayed, treated or cured. Left unchanged, its annual cost will top $1.5 trillion by 2050.

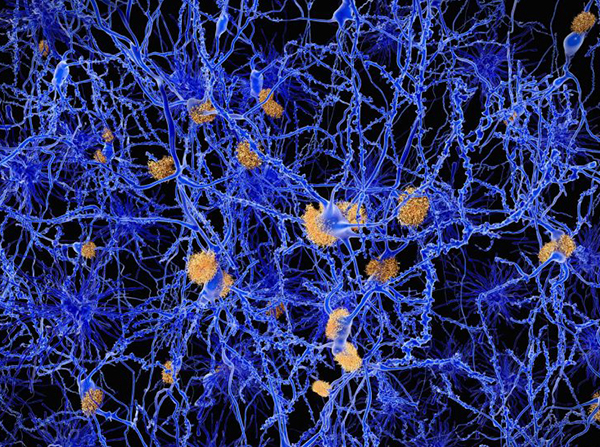

Despite many disappointments in research over the past 30 years, Aisen said “we have learned a great deal and we are now close” to major progress. Among those lessons are that amyloid buildup in the brain drives the disease, that early intervention — long before symptoms appear — may be essential and that advances in blood-based biomarkers are enabling progress toward primary prevention of Alzheimer’s.

“There are no discrete clinical stages,” he said. Alzheimer’s is “a continuum,” probably stretching over 25 years of a patient’s life.

Aducanumab, a monoclonal anti-amyloid antibody, had failed in previous trials because it targeted people with advanced cases in which amyloids had already irreversibly damaged the brain. But it did clear out amyloids, Aisen said, which means that if individuals can be identified early in the continuum, major progress in treating the disease might be possible.

“The entire field has changed dramatically with the advent of amyloid PET and tau PET imaging,” he said. “We can now see lesions of the brain longitudinally in living people.” Perhaps more important, cheaper plasma tests may be just as accurate as PET scans.

Aisen noted that two international trials of anti-amyloid immunotherapy in asymptomatic patients have been launched at ATRI.

About 6 million Americans are known to have symptomatic Alzheimer’s, but another 14 million may have pre-dementia and asymptomatic Alzheimer’s, he said, noting that if the trials are successful he envisions people getting screenings at age 45 to 50 and beginning therapies to get rid of amyloids, much as statins today reduce long-term vascular disease.

“We are close to major breakthroughs,” he said.

Aisen was joined in a panel discussion by Sharon Cohen, medical director of the Toronto Memory Program, and Heather Snyder, vice president of medical and scientific relations at the Alzheimer’s Association. The panel was moderated by Schaeffer Center Director Dana Goldman.

Cohen noted several barriers to a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s, including difficulty in recognizing the difference between the disease and normal aging, and reluctance of physicians to push for diagnosis since no treatment is available. Snyder added that as we understand more about the biology of the disease, we should also push for more lifestyle interventions. Aisen agreed, noting that diet, physical activity and cognitive activity can improve brain resilience.

A second panel discussion on how to pay for novel treatments for Alzheimer’s was kicked off by Schaeffer Center Director of Research Darius Lakdawalla. He noted that 132 drugs are in the pipeline, many of which aim to reach people early in the disease continuum. But that sets up a conundrum: Private insurers will bear more of the cost and less of the benefit since treatment often will be initiated before age 65 but visible benefits will occur after age 65, when Medicare kicks in.

“The misalignment of incentives may limit reimbursement and incentives for treating patients early,” he said. “How can we better align costs and benefits?”

He suggested using USC’s Future Elderly Model microsimulation to estimate long-term health consequences of functional and cognitive decline and associated costs. The model could then inform a pricing strategy that would better reflect the lifetime health burden of Alzheimer’s.

Lakdawalla was joined by Steve Miller, chief clinical officer at Cigna Corporation, and Sarah Lenz Lock, senior vice president for policy and brain health at AARP.

Miller said that the old model of payment is not sustainable for Alzheimer’s medications and other drugs that show the same cost-benefit misalignment that Lakdawalla outlined. Aducanumab might provide an early test for payment reform, he said, depending on what the FDA demands in a use label. If, for example, a PET scan is required before a prescription can be written then the cost will be very high.

“Will the drug be aimed at 1.5 million people or 20 million people?” Miller asked.

Lock said “we need to start changing the conversation” on payments. If innovative drugs reduce the risk of getting Alzheimer’s by 20% to 40%, or if it can delay onset by five years, the overall cost burden could be cut in half.

Lakdawalla noted that a successful treatment plan for Alzheimer’s means treating a lot of people with no symptoms. “We need a system that looks long term,” he said.

“Affordability and access are the key issues” in payments, Miller said. “If we keep patients in mind first, we ought to get to the right solution.”