Editor’s Note: This analysis is part of USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative on Health Policy, which is a partnership between Economic Studies at Brookings and the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings.

Since the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) health insurance marketplaces first took effect in 2014, news story after story has focused on premium increases for certain plans, in certain cities, or for certain individuals. Based on preliminary reports, premiums now appear set to rise by a substantial amount in 2017.

What these individual data points miss, however, is that average premiums in the individual market actually dropped significantly upon implementation of the ACA, according to our new analysis, even while consumers got better coverage. In other words, people are getting more for less under the ACA.

Covered California, that state’s marketplace, just announced premium increases averaging 13.2 percent. But even if premiums increase by the 10 or 15 percent overall that some are predicting for 2017, they will still be far lower than premiums otherwise would have been in the absence of the law. Moreover, this analysis does not include the effects of premium and cost-sharing subsidies that serve to make ACA marketplace plans more affordable for many people.

2014 Premiums In The ACA Marketplaces Were 10-21 Percent Lower Than 2013 Individual Market Premiums

While many stories of pronounced increases are simply the natural result of a law that works differently in every region and for people of different health statuses, it appears to be conventional wisdom that the ACA increased premiums in the individual, non-group insurance market, if only because it increased the quality and robustness of coverage. Indeed, many of the ACA’s new rules do have the anticipated effect of increasing premiums, such as:

- mandated guaranteed issue regardless of health status;

- restrictions on the ability to charge different premiums based on anything besides age and smoking habits;

- requirements for plans to offer certain benefits deemed “essential;”

- limits on out-of-pocket costs an enrollee can pay for covered services in a given year; and,

- the elimination of any lifetime limits on coverage.

However, many features of the ACA push in the opposite direction and save consumers money. The individual mandate and federal subsidies greatly expanded the number of people purchasing coverage in the individual market, pushing premiums down both by increasing the sheer size of the market—the bigger the market, the lower the prices—and including many healthier people who previously went uninsured. In addition, the ACA created relatively transparent marketplaces where insurers must compete on premiums for products standardized by actuarial value, allowing competition to drive down prices.

Together, by creating a much larger and more competitive market, these changes placed strong downward pressure on insurance premiums, outweighing the factors pushing in the opposite direction. Stronger rate review and minimum requirements for how much an insurance plan must spend on actual health care expenses furthered this downward pressure on prices.

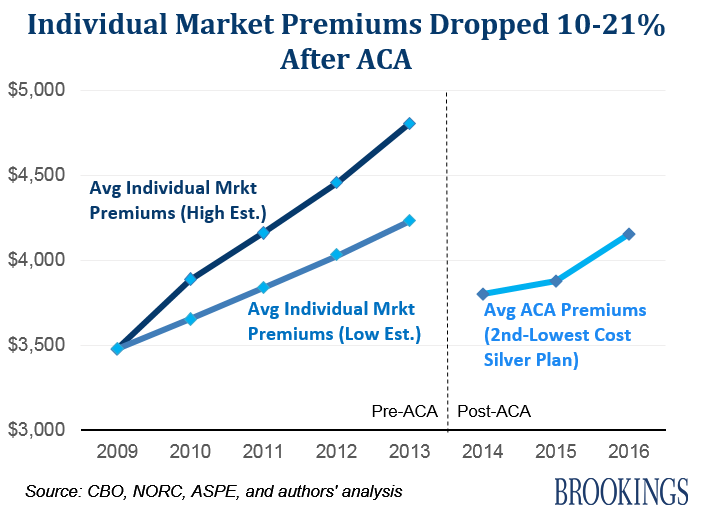

According to our analysis, average premiums for the second-lowest cost silver-level (SLS) marketplace plan in 2014, which serves as a benchmark for ACA subsidies, were between 10 and 21 percent lower than average individual market premiums in 2013, before the ACA, even while providing enrollees with significantly richer coverage and a broader set of benefits. Silver-level ACA plans cover roughly 17 percent more of an enrollee’s health expenses than pre-ACA plans did, on average. In essence, then, consumers received more coverage at a lower price.

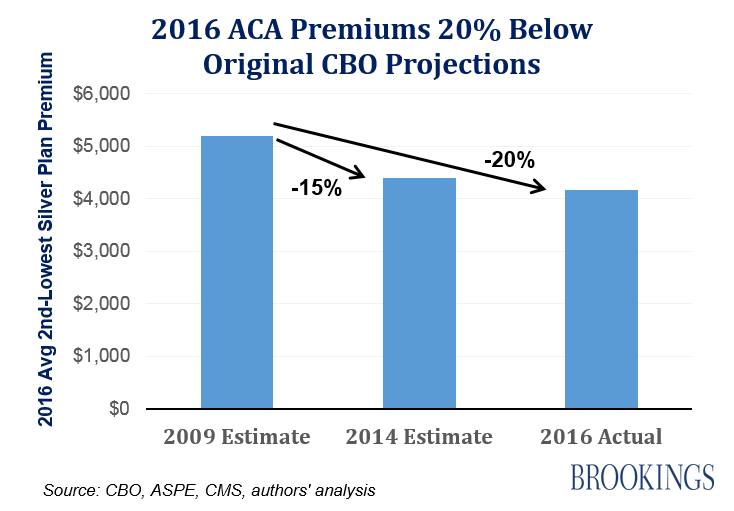

Moreover, ACA marketplace SLS plan premiums are still lower in 2016 than individual market premiums were in 2013, on average, and a full 20 percent below where the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) originally projected they would be when they first estimated the impacts of the ACA in 2009.

Health insurance was expensive before the ACA and continues to be, but the ACA appears to have had a salutary impact on premiums even while providing more robust coverage. Judging by the low or negative profits for many insurers on their ACA plan offerings and preliminary reports indicating significant marketplace premium increases for 2017 in many areas, premiums to date were likely set lower than they should have been. However, barring increases much larger than foreseen today, premiums are likely to remain notably below expectations, or where they would have been in the absence of the ACA.

For this analysis, we generally focus on average premiums for the second-lowest silver marketplace plan because they determine federal premium subsidies and represent the most common coverage level. CBO also provides good data on such plans, and this metric allows us to compare actual experience to the original predictions. A “silver” plan is one that has an actuarial value of 70 percent, meaning it pays for roughly 70 percent of the average enrollee’s covered health expenses.

While not a pure apples-to-apples comparison, the finding that SLS plans are available for a lower cost than individual market plans before 2014, on average, is significant. This is particularly true given that SLS plans have an actuarial value roughly 10 percentage points higher than the average for individual plans prior to 2014 (and thus pay roughly 17 percent more of an enrollee’s covered health care expenses).

Beating CBO’s Expectations

In 2014, the Congressional Budget Office highlighted that ACA premiums had come in 15 percent lower than expected, but premiums since then have continued to grow slower than projected (the average SLS plan premium grew at 2 percent in 2015 and 7.2 percent in 2016 in the federally-facilitated exchanges), increasing the difference in 2016 to 20 percent.

Some of this decline is the result of the impressive system-wide health care spending slowdown the nation has experienced in recent years, which is broader than just the ACA and is due in part to the slower than expected economic recovery (though growing evidence suggests that the ACA has played some role).

However, ACA marketplace premiums have beaten projections by significantly more than other areas of health care spending, therefore implying that the marketplaces have been particularly effective in driving low premiums. By comparison, premiums for employer-sponsored health plans (which the ACA only minimally impacts) in 2014 were roughly 12 percent below CBO projections from the same 2009 report and total national health spending in 2014 was about 7.5 percent lower than projected back when the ACA was enacted.

The ACA’s Effect On Individual Market Premiums

To address this issue, we draw on Congressional Budget Office estimates of average individual market premiums in 2009 (the most recent pre-ACA year for which CBO provides an estimate), largely based on data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) and adjusted for insights from their Health Insurance Simulation Model and observed data. We then adjust this estimate downward to account for it being based on pre-2009 data, by the ratio of actual 2009 employer-provided plan premiums for single coverage (from MEPS) to CBO’s predictions at the time.

Therefore, we estimate that the average annual premium in the individual market in 2009 was $3,480 (or $290 per month), which was for a plan that on average covered roughly 60 percent of an enrollee’s covered health expenses — an actuarial value of 60 percent.

By comparison, the average premium in 2014 for the SLS plan was $3,800 according to CBO, only 9 percent higher despite the passage of five years. Adjusting for the difference in actuarial value, this premium was actually lower in nominal dollars than that in 2009.

Moreover, by any measure, individual market premiums had grown enough by 2013 such that the $3,800 average SLS plan premium in 2014 represented a sharp drop from the previous year, despite covering a higher percentage of enrollee costs and offering a broader set of health benefits.

Jon Gabel and Stephen Smith of NORC at the University of Chicago conducted the most thorough analyses of how much premiums in the individual market increased between 2009 and 2013, before the ACA marketplaces took effect. Gabel and Smith analyzed data on rate increase filings for comprehensive health insurance products from a sample of states and found that individual market premiums grew by 11.7 percent in 2010, 7 percent in 2011, and 7.1 percent in 2012. A subsequent Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation (ASPE) analysis by Rose Chu and Richard Kronick, also looking at public insurer rate filings to states, found that individual market premiums in 2013 grew by 7.9 percent in their data sample.

These analyses are imperfect and tell us more about increases in base premium rates offered (before underwriting) than average premiums paid. Nevertheless, they imply that ACA marketplace premiums for the SLS plan in 2014 came in a remarkable 21 percent lower than average individual market premiums the year prior, or 32 percent lower when accounting for the new plans’ higher actuarial value, even without incorporating likely utilization increases in response to the additional coverage.

Other data sources indicate that individual market premiums may have grown more slowly from 2009-2013 than the two ASPE studies found, but suffer from other limitations. An analysis by eHealth, a company that sells health insurance policies online, found that premiums for their customers on the individual market grew by 5.2 percent per year, on average, for single plans from 2009 to 2013. It is possible, though, that their customers are unrepresentative of the full market, as people buying insurance online might differ from those buying coverage through other means, differences that might have changed over this period of expanded online purchasing. Nonetheless, premiums for employer-provided health insurance (on which better data exists) also grew by roughly 5 percent annually over that time period, both according to data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey (MEPS) and the Kaiser Family Foundation / Health Research & Educational Trust Employer Health Benefits Survey.

Even if average individual market premiums grew at only 5 percent annually from 2009 to 2013, then, ACA marketplace premiums for the SLS plan in 2014 still represented a 10 percent decline from the average individual market premium in 2013, or a 23 percent drop for a plan of the same actuarial value (again before incorporating likely utilization increases in response to additional coverage).

Is it important to note, though, that while average individual market premiums appear to have declined nationwide upon implementation of the ACA, local conditions can vary significantly because premiums are determined separately for each local marketplace. Similarly, due to its community rating provisions, the impacts of the ACA on individuals’ premiums may vary significantly based on health status — the ACA is more likely to increase premiums for healthier enrollees and decrease them for sicker enrollees.

Supporting Evidence

An analysis by Jon Gabel in Health Affairs Blog, examining base premium offerings in the individual market, lends further evidence to our new finding. He utilizes data from America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) that show base individual market premiums averaging $2,985 in 2009.

Suppose that base premiums subsequently grew annually by somewhere between 5 percent and the higher ASPE estimates detailed earlier from 2009-2013. That would then imply that average base premium offerings in the individual market in 2013 were similar to the $3,800 average premium for the SLS plan on ACA marketplaces in 2014 (anywhere from 8 percent lower to 5 percent higher).

Base health insurance premium rates before the ACA, though, are by definition lower than the actual premiums paid by many enrollees, given the ability to charge higher premiums based on a myriad of factors, including poor health status or gender, in the pre-ACA individual market. It is no surprise, then, that our estimate (based on CBO analysis) of average premiums paid in 2009 is 17 percent higher than AHIP’s finding of base premium rates that year.

How Did The ACA Lower Individual Market Premiums?

That the ACA might have caused premiums to drop so precipitously when its marketplaces took effect may seem surprising at first — it was to us. After all, the ACA prohibited insurers from denying coverage or charging higher rates to sicker individuals, required them to cover a broader set of benefits, and imposed new taxes and regulations. However, the premium reductions make more sense upon deeper analysis.

First, even though sicker people were charged higher premiums in the pre-ACA world (and some were denied coverage altogether), many still purchased insurance, but likely at significantly higher rates; as noted above, this made average premiums in the pre-ACA individual market notably higher than the base rates available to the healthy. Moreover, by creating large premium subsidies and imposing the individual mandate, the ACA may have caused a greater influx of relatively healthy enrollees into the individual market in 2014 and beyond, which was the hope all along. CBO, in fact, originally predicted that the ACA would create a healthier risk pool in the individual market by 2016, on average, than existed before 2014 (although we have not seen evidence in either direction as to whether this prediction came to fruition).

Second, the ACA creates a price-competitive and transparent market structure, where consumers can compare similar health insurance products. ACA marketplace consumers, to date, appear to be very cost-conscious and drawn to lower-cost, narrower-network offerings. As a result, many health plans have been very aggressive in negotiating lower provider payment rates and utilizing narrow networks to help do so; a McKinsey Center for U.S. Health System Reform analysis finds that narrow-network silver plans offered median premiums 22 percent lower than broad-network plans in 2016.

Third, selling costs are likely to be lower in the ACA marketplaces because of the prohibition on medical underwriting and limited variation in the policies and policy riders that can be offered. Higher enrollment also provides insurers more enrollees over which to split their fixed costs. The structure of the marketplaces, by presenting all insurance options to consumers on a single platform, should also somewhat reduce the need for marketing expenses and commissions paid to brokers.

Evidence additionally suggests that the impositions of medical loss ratio minimums (the percentage of revenue insurers must spend on enrollee health expenses) and more prevalent rate review have had a small impact in lowering premiums. Programs that limit insurers’ risk, such as reinsurance and risk corridors, also have the effect of keeping premiums down, although both are expiring after this year and Congress has restricted risk corridor payouts.

Outlook For 2017: Premiums Below What They Would Have Been Without The ACA

This analysis finds that ACA marketplace premiums have been quite low to date. Indeed, it is likely that premiums through 2016 have been too low to be sustainable in many cases given the financial difficulties many insurers are having, whether the result of underestimating the cost of serving new populations, loss leader strategies to build a customer base, or other reasons. It is not surprising, then, that we are seeing higher premium increase requests for 2017.

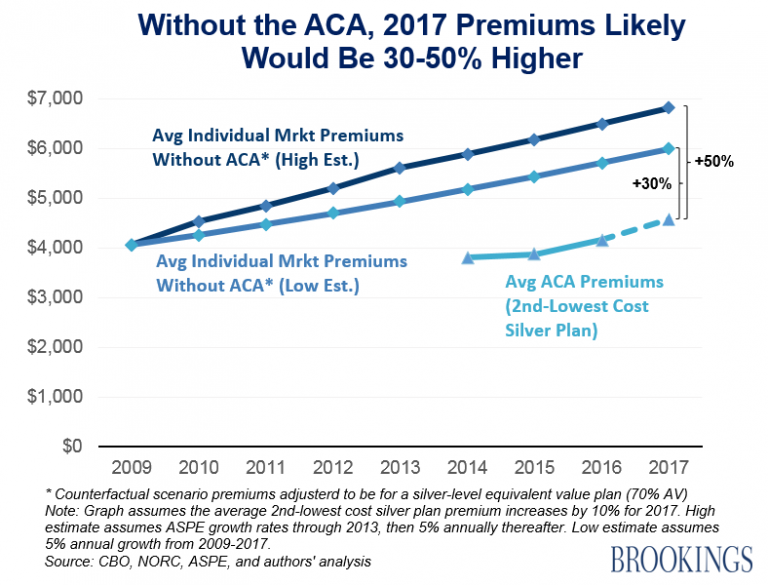

Large premium increases for 2017, if they do occur, would certainly be jarring to existing enrollees (although federal premium subsidies would soften the impact for low- and middle-income consumers). However, even if ACA marketplace premiums grow significantly in 2017, they will still be much lower than individual market premiums would have been in the absence of the ACA, on average, according to our analysis. This finding holds true under any reasonable set of assumptions about premium growth in the individual market in the counterfactual scenario that the ACA was never enacted.

For instance, this analysis indicates that had premiums grown at 5 percent annually after 2013 in the absence of the ACA, average individual market premiums in 2017 for a 70 percent actuarial value plan (equivalent to “silver” level under the ACA) would have been between 30 and 50 percent higher on average than actual ACA premiums will be in 2017 for the second-lowest cost silver plan — even if marketplace premiums increase by 10 percent next year. Put another way, ACA premiums would have to grow by more than 44 percent in 2017 to approach where individual market premiums would have likely been in the absence of the ACA, even under conservative assumptions.

Similarly, average premiums in the individual market even for less robust coverage (60 percent vs. 70 percent actuarial value) would have been between 12.5 and 28 percent higher than 2017 ACA premiums are set to be for the SLS plan if premiums grow by 10 percent next year.

The low-end estimates above assume individual market premiums also grew at 5 percent annually from 2009-2013, while the high-end estimate assumes they grew at the higher ASPE estimates during that period before slowing to 5 percent annual growth after 2013.

Lessons Learned

The ACA marketplaces, though imperfect, represent a clear improvement over the unstructured, non-transparent individual health insurance market that existed beforehand. They have been quite successful in lowering premiums for consumers while simultaneously providing better insurance. While guaranteed issue, required essential benefits, and restrictions on medical underwriting undoubtedly pushed up premiums, aspects of the ACA that created a far more competitive individual insurance market appear to have more than offset those effects. As a result, individual market premiums in 2014 were lower than they were in 2013 and lower than they would have been absent the ACA.

Experiences do differ widely across the nation, though, so consumers in some regions have fared more poorly and some markets suffer from minimal competition. The results of this analysis do not mean that no work remains. Health reform is an ongoing challenge, and there is still much room to increase the quality and competitiveness of marketplaces.

You must be logged in to post a comment.