Unnecessarily prescribed antibiotics for colds and other respiratory infections can weaken immune systems and have helped give rise to “superbugs.” These antibiotic-resistant bacteria attack approximately 2 million people each year in the United States alone — of which nearly 23,000 will die. In addition, antibiotics are often the wrong treatment for such infections, so millions of dollars are wasted annually on failed therapies. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), nationally, some 30 percent of all antibiotic prescriptions for acute respiratory infections — more than 47 million per year — are inappropriate.

To help save lives and resources, Jason Doctor leads research efforts using behavioral economics to prompt physicians toward appropriate prescribing. Three of his “nudges” have been shown to dramatically improve physician prescribing, including:

- Posted Pledges — The physician hangs a poster in the examination room that explains safe antibiotic use and includes a signed promise to adhere to proper prescription guidelines.

- Accountable Justification — This prompt appears as the physician updates a patient’s electronic chart, asking the doctor to justify any antibiotic prescription for acute respiratory infections.

- Peer Comparison — The physician receives a periodic email ranking his/her inappropriate antibiotic prescription rates against those of top-performing doctors.

Each has proven effective, with the posted pledges alone cutting overprescriptions by 20 percentage points. Of note, these nudges are relatively inexpensive to institute, providing a cost-effective approach to a pressing health issue.

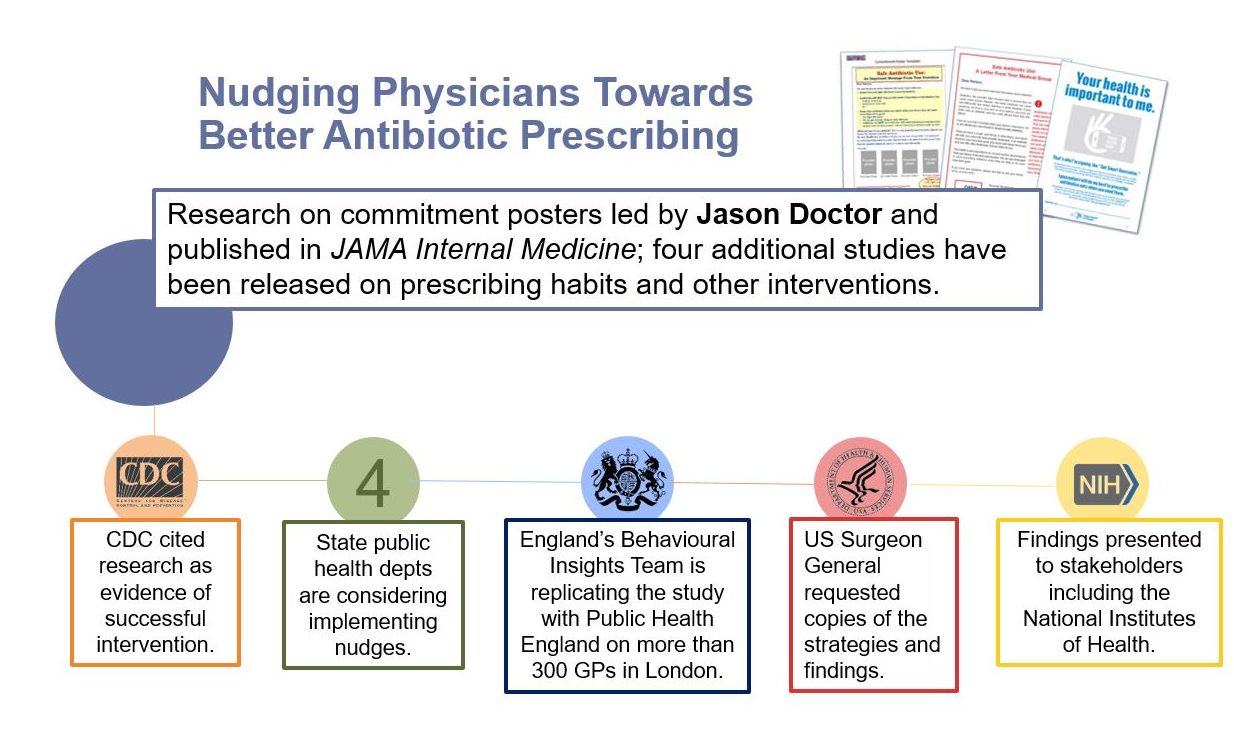

As a result, a growing number of states and the United Kingdom have implemented these measures. The CDC cites the poster initiative as a “best practice.” Meanwhile, the U.S. surgeon general requested details about the strategies and findings, which also have been drawn upon by the National Institutes of Health and other organizations.

The success of these interventions stems from a recognition of the human feelings and frailties of physicians. Previously, “most efforts to reduce antibiotic prescribing involved education, reminders or giving financial incentives to physicians,” says Doctor, Schaeffer Center director of health informatics. “We decided to test if socially motivated interventions, such as instilling pride in their performance or making physicians accountable for their decisions, would help address the problem.”

Our studies suggest that simple and inexpensive tactics, grounded in scientific insights about human behavior, can be extremely effective in addressing public health problems.

Best Practices for Better Results

Doctor’s research has shown that these types of nudges have a significant impact on prescribing:

- Posted pledges reduced inappropriate prescribing by 20 percentage points relative to the control group in their trial.

- Accountable justification resulted in an 18-percentage-point reduction in inappropriate prescribing.

- Peer comparison resulted in a 16-percentage-point reduction.

Based on the poster study’s positive results, scaling just this one low-cost nudge to reach the entire nation would lead to 2.6 million fewer unnecessary antibiotic prescriptions — saving $70.4 million.

The nudges also are easy to implement and account for physicians’ busy schedules. “These interventions are low-cost and allow the prescribing clinician to retain their decision-making authority while nudging them toward better practices,” Doctor says.

Cause and Effect

Doctor didn’t stop at implementing nudges to change physician behavior though. He also looked at how fatigue and decision-making play a role. The team pinpointed a major cause of unnecessary prescriptions — fatigue resulting from pressure, repetition and long hours. The investigators found that the number of prescriptions increased as the workday progressed. The probability of a prescription for antibiotics increased by 1 percent in the shift’s second hour, 14 percent in the third hour and 26 percent in the fourth. This aspect could probably be solved by better decision support for physicians, modified schedules, fewer continuous work hours and mandatory breaks, the researchers found.

Another study showed that simply regrouping how prescription options are displayed in electronic treatment menus makes a difference. Physicians were roughly 12 percent less likely to order antibiotics unnecessarily if the options were grouped together rather than listed individually.

“Taken together, our studies suggest that simple and inexpensive tactics, grounded in scientific insights about human behavior, can be extremely effective in addressing public health problems,” wrote Doctor and fellow researchers in The New York Times.

Back to Bad Habits

Given the high success and low cost of these strategies, hospitals and clinics might consider implementing them permanently. For a follow-up study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association, the team assessed what happened when the interventions were stopped — and, indeed, some clinicians returned to issuing unnecessary prescriptions.

Twelve months after the peer-comparison intervention ended, clinicians increased their antibiotic prescription rate from 4.8 to 6.3 percent. The rate also increased from 6.1 to 10.2 percent among clinicians who were no longer asked to justify their prescriptions. These results underscore the need to adopt these interventions over the long term to ensure continued success.

Using Insights Learned to Reduce Opioid Prescribing

In August 2018 Science published a study by Doctor that honed in on an important gap in the care system: many clinicians never learn of their patients’ deaths from overdoses. The nudge was simple: Half the study’s participating physicians received a letter from the county medical examiner when a patient to whom they had prescribed opioids suffered a fatal overdose. In the following three months, the clinician’s opioid prescribing decreased by nearly 10 percent compared to the group not receiving a letter. In addition, they were 7 percent less likely to start a new patient on opioids or to prescribe higher doses.The results are particularly promising since traditional state regulations have not had much impact on the epidemic. Numerous local and state agencies have already contacted Doctor for guidance on implementation including the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors who voted unanimously fora feasibility study aimed at using this tactic.

You must be logged in to post a comment.