Summer’s grieving mother, Jeanine, clings to her picture. Jeanine wanted Summer’s story told in hopes of helping others. (Tomas Ovalle / Special to The Chronicle)

Editor’s note: This story was first published in the San Francisco Chronicle on Oct. 13, 2019 and written by Ariane Lange.

On July 29, 2015, police brought a 27-year-old woman to the psychiatric emergency room at San Francisco General Hospital. Her name was Summer.

She’d been hallucinating when she was picked up and seemed agitated even after multiple rounds of antipsychotic drugs. Unsure whether Summer might have an underlying physical illness, medical providers moved her between the psychiatric ER and the medical ER for at least two days before she was sent home with no follow-up care.

Over the next 10 months, as her mental health worsened and she became homeless, medical records show she cycled in and out of the psychiatric ER at least 28 times, repeatedly discharged with instructions to seek help from the same piecemeal services for low-income and homeless San Franciscans that weren’t working for her.

Summer encountered the same hurdles that many frequent users of emergency services in San Francisco face: overcrowded and understaffed ERs, daunting wait-lists for long-term psychiatric care and no case manager to help navigate complicated health and housing systems.

On May 22, 2016, just two weeks after her last admission to the psychiatric ER, Summer killed herself. A police officer and a chaplain visited her parents to tell them the daughter they’d known as a voracious reader and a halfhearted runner had died. Her mother, Jeanine, answered the door. “I couldn’t process it,” she said. Three years later, she can barely talk about her daughter’s death. She shared Summer’s medical records with The Chronicle, but at the family’s request, The Chronicle is not using Summer’s last name, in accordance with its policy on identifying sources.

San Francisco’s Behavioral Health Services system helps many of the 30,000 people it works with every year, and many receive high-quality or even lifesaving treatment. But Summer’s experience highlights weaknesses in the $370 million system — a system Mayor London Breed and the Board of Supervisors say is broken.

In March, Breed appointed a director of mental health reform, former psychiatric ER head Dr. Anton Nigusse Bland, to review the system. Nigusse Bland has since said the department will prioritize helping 200 or so people who are the most frequent ER users.

The Department of Public Health has also staffed up at the psychiatric ER, adding two social workers and four peer navigators, while opening more treatment beds outside the hospital. After a Chronicle investigation found that some treatment beds at S.F. General and outside providers sit empty every night, the department said it would create a real-time inventory of open treatment spots.

“There are gaps in our city’s health system,” said Jenna Lane, a department spokeswoman. “We are constantly working to bridge them.”

Summer’s story shows how the city can fail its most vulnerable clients. It’s one familiar to more than 30 San Francisco social workers, doctors, nurses, advocates and psychiatric patients interviewed for this report, who described a mental health care system that helps many patients only when they’re at their lowest point, and routinely fails to prevent their next crisis.

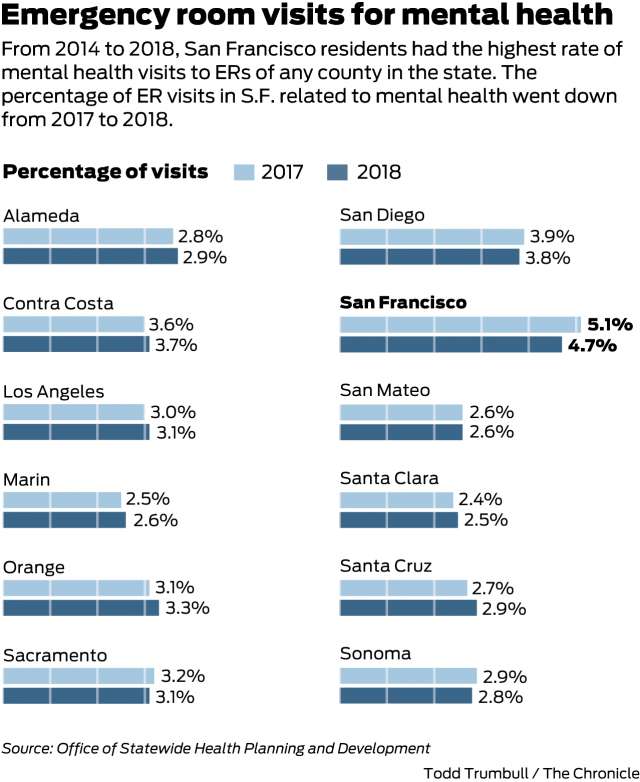

Psychiatric patients like Summer are flooding S.F. General. Data show that 8,203 people visited the psychiatric ER last year — a four-year high. According to a 2018 city audit of Behavioral Health Services, 70% of visits to the psychiatric ER in the 2016-17 fiscal year were by homeless patients.

The best many of these people can hope for is what mental health care providers call a “tuneup.” James Abbeduto, 36, is typical. He went to the ER for substance abuse or suicidal thoughts at least 16 times over a year before he was evicted from his apartment in 2018 and became homeless, according to discharge papers he allowed The Chronicle to examine.

“I go in there, like, ‘Look … I need help. I need to see a doctor.’ They’ll keep me for a couple hours, and they’ll give me a pill, and they’ll just let me go,” said Abbeduto, who remains homeless. He said he had asked repeatedly to be transferred to an inpatient unit. But, he said, he wasn’t considered sick enough.

Cecily Donegan, a social worker in UCSF Medical Center’s emergency department, said experiences like Abbeduto’s are common. Long wait-lists for residential treatment services mean there’s often nowhere to send patients once they’re stable enough to leave the hospital. Because of these gaps, she said, “it’s almost like mental health care is being completely done in the ER(s).” And ERs frequently discharge homeless patients back to the streets, she said, even though homelessness aggravates their mental health and substance abuse problems.

“In psych emergency, it was very, very typical for people to just go back to the street,” said Jennifer Esteen, a former psychiatric ER nurse at S.F. General who now works directly for the Department of Public Health.

Broken_summer_promo from San Francisco Chronicle on Vimeo.

Summer graduated from UC Riverside with a degree in political science in 2009. About two years later, she moved to San Francisco. For most of her time in the city, she was in sporadic contact with family members.

After her initial involuntary visit to the psychiatric ER, Summer kept coming back, often voluntarily. She was depressed, her medical records show, and self-medicating with alcohol and sedatives as well as cocaine and methamphetamines. Doctors quickly diagnosed her with schizophrenia.

Doctors prescribed her antidepressant, antipsychotic and anti-anxiety drugs, which she took irregularly. She told her doctors that one drug quieted her hallucinations. Starting in fall 2015, she told doctors consistently that voices in her head were telling her to harm herself.

In October 2015, doctors at the psychiatric ER sent her to Shrader House, an acute diversion unit where people can stay for up to 14 days and get therapy, food and shelter. But when she told workers that voices were telling her to jump out of a window, they sent her back to the psychiatric ER. After six hours there, she was sent back to Shrader. The next week, she returned to the psychiatric ER, saying she was suicidal.

At least twice, staff at S.F. General said Summer needed a case manager. According to her records, she never got one.

In San Francisco, there aren’t enough case managers to meet demand. The most vulnerable patients are assigned to intensive case managers — who have fewer clients and are more involved day-to-day. A 2018 city audit of Behavioral Health Services said that about 2,200 largely homeless people use emergency services frequently, and only 11% of them were assigned an intensive case manager in the 2016-17 fiscal year. The audit found that for each adult discharged from intensive case management between 2012 and 2017, two more were waiting for those services.

Since the audit, the Department of Public Health has added six intensive case managers, said Lane, the spokeswoman. The department is budgeted for 78 intensive case managers, but about 20% of the positions are vacant due to the difficulty of hiring staff. Even with full staffing, the department could serve only about 1,300 clients.

Without a case manager, behavioral health patients often leave an ER with little more than a list of walk-in hours for clinics that offer follow-up care, according to doctors, nurses, advocates and patients. Records show Summer got those referrals, even after she became homeless. Dr. Christopher Colwell, chief of emergency medicine at S.F. General, said many patients need more help than that.

“Are we doing an adequate job of helping them really follow up to the extent that they need?” Colwell said. “I’d say the answer is no.”

In December 2015, months after doctors recommended that she receive case management services, records show that S.F. General’s medical ER gave Summer reading material titled, “Suicidal Feelings — How to Help Yourself.”

A few weeks later, after she fell behind on her $865-a-month rent, Summer’s landlord evicted her. The apartment was her last permanent housing.

In San Francisco, some patients experiencing a mental health emergency go straight to the psychiatric ER. But in many cases, including when the psychiatric ER is full, they go instead to a medical emergency room.

In the medical ER at S.F. General, four rooms are designated for psychiatric patients deemed at risk of harming themselves or others.

ER nurses Will Carpenter, Jenna Marchant and Heather Bollinger said that when the four rooms are full, patients end up in hallways, and are sometimes watched over only by clerks instead of trained staff. Colwell, S.F. General’s emergency medicine chief, said he couldn’t confirm or deny that, but acknowledged, “We constantly have more patients with psychiatric issues than we have room for.”

In the first three months of this year, psychiatric ER staffers filed at least 17 complaints to their union asserting there weren’t enough medical providers and support workers to serve patients. In 13 of those complaints, staffers said they had to work shifts that violated hospital policies on staff-to-patient ratios.

Dr. Mark Leary, deputy chief of S.F. General’s psychiatry department and acting head of the psychiatric ER, said managers do “everything they can” to staff up when there’s a surge of patients. Such surges, Leary said, are often tied to a lack of appropriate places to discharge the most complex patients.

The psychiatric ER was on “condition red” — so full that ambulances are diverted to other ERs — 35% of the time between January and June 2019, according to the department.

The lack of acute inpatient beds— where those in crisis can stay for longer periods after they’ve stabilized at the psychiatric ER — contributes to the overcrowding. The county mental health system has only 44 such beds.

The resulting backup leaves people stuck in emergency rooms. Dr. Maria Raven, UCSF chief of emergency medicine, said patients “end up in our emergency department for very, very long periods of time. Sometimes days.” Raven said “it’s an awful, awful” situation.

Others are kept in locked wards because of a shortage of “step-down” beds. One 24-year-old woman said she had to remain in a locked acute unit at S.F. General for seven months before a spot opened in an unlocked residential home in May 2019. During that time, she was taking up a spot someone else likely needed.

In January 2016, after being evicted from her apartment, Summer was in and out of both the ER and psychiatric ER at S.F. General multiple times, receiving treatment for suicidal thoughts and psychotic episodes.

From Jan. 8 to 11, she was in a locked inpatient unit. According to her medical records, her doctor said she needed to be connected to “more intensive (outpatient) services.” Toward the end of the month, another doctor noted before discharging her that Summer’s visit to the psychiatric ER was her 25th.

On May 3, she was back in the psychiatric ER “asking for help with (auditory hallucinations) telling her to kill herself and others,” records show. On May 9, Summer was there again. She told a doctor she was hearing voices telling her to kill herself. Again, she was discharged after an unspecified period of time.

Two weeks later, on May 22, 2016, Summer died of blunt force trauma injuries after she jumped off the Golden Gate Bridge.

Before her death, Summer had been calling home multiple times a day, saying she wanted to die. Her mother, Jeanine, 200 miles away in the Central Valley, said she felt powerless, “begging her to come home.” Until Jeanine obtained her daughter’s medical records, she did not know that she had been asking for help from San Francisco’s behavioral health system since at least August 2015.

Her family finds it painful to talk about her death. But Jeanine said she decided to share her daughter’s records in hopes of helping others.

“I felt like if Summer could do anything, she would want to help people who are poor to get better health care treatment,” Jeanine said. “Especially with mental health services. She would really want that, because that was something that she wasn’t able to get for herself.”

Ariane Lange writes for the Center for Health Reporting at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. Reporting was supported by a grant from the California Mental Health Services Oversight and Accountability Commission.

You must be logged in to post a comment.