The map identifies nearly 1 in 4 neighborhoods — representing millions of Americans — as pharmacy shortage areas.

USC’s Dima M. Qato spent more than a decade working as a community pharmacist and public health advocate in underserved refugee and immigrant communities in Chicago.

Through her experiences and public health training, Qato — the daughter of a pharmacist and now an associate professor at the USC School of Pharmacy — has come to view pharmacy access as a human rights issue. Pharmacies are a frequently overlooked piece of the health care access puzzle.

As a pharmacist, she observed that people in low-income neighborhoods were taking days off work just to pick up their medications. And in some cases, they did not pick up their medications at all if the medicine was not in stock and the prescription had to be filled at another pharmacy farther away. Patients in high-income, mostly white neighborhoods did not really experience these access barriers, Qato said.

“The World Health Organization has considered geographic access to pharmacies as one of the key determinants of access to essential medicines for decades,” said Qato, an associate professor who holds the Hygeia Centennial Chair at the School of Pharmacy and is a senior fellow at the USC Leonard D. Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics.

“Despite the important role of pharmacies in providing essential medicines to the community, 15 years ago, when I started my PhD, no one really considered pharmacy access — not even people investigating health equity and disparities in medication adherence,” she added. “It wasn’t part of the conversation. So, I started asking questions.”

Designing a map that identifies ‘pharmacy deserts’

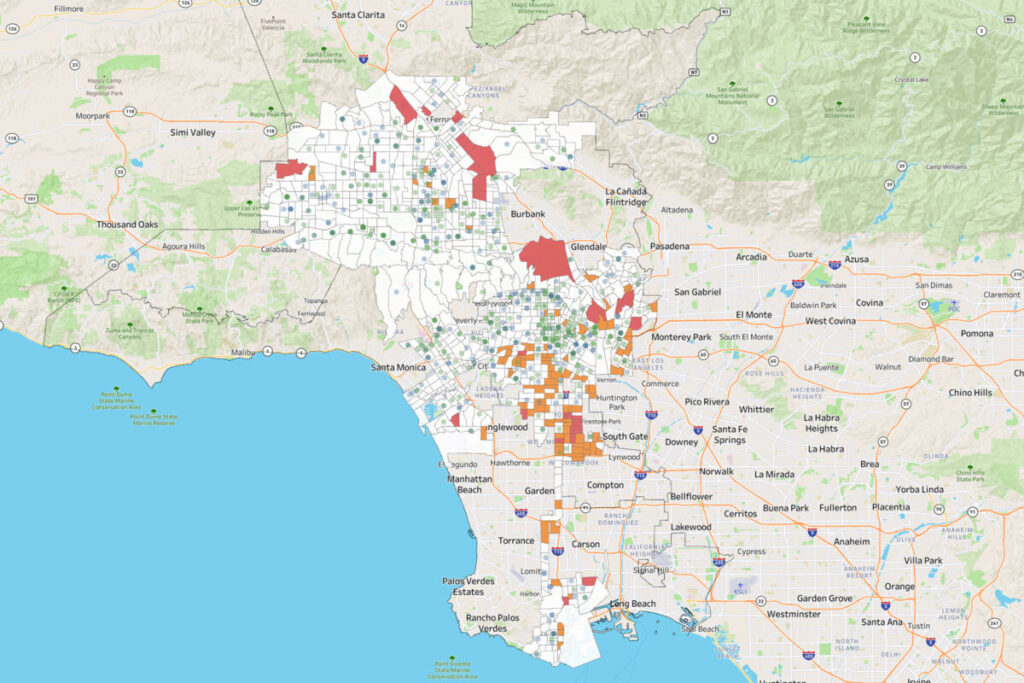

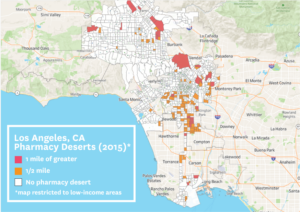

Her latest project is an interactive, nationwide mapping tool showing the location of every pharmacy in the United States and which neighborhoods fall into the category of “pharmacy deserts,” or pharmacy shortage areas. The Pharmacy Access Initiative is a collaboration with the School of Pharmacy, the USC Schaeffer Center, the Spatial Sciences Institute at the USC Dornsife College of Letters, Arts and Sciences and the National Community Pharmacists Association, which represents independent pharmacies around the country.

Sign up for Schaeffer Center news

The map identifies nearly 1 in 4 neighborhoods — representing millions of Americans — as pharmacy shortage areas.

“Dr. Qato has spent several years thinking about various barriers to pharmacy access and how these impact equity in health care — her work has defined and measured the idea of pharmacy deserts in urban areas around the U.S.,” said Robert Vos, an associate professor (teaching) of spatial sciences, who helped build the tool. “We combined her insights about pharmacy access with spatial thinking and computing. By collaborating, we have been able to attack the problem on a national scale using faster spatial computation and spatial analysis to better understand geographic contexts, like urban versus rural areas.”

The tool can serve multiple purposes that could influence policy and improve public health.

Mapping pharmacy deserts

First, the map defines a pharmacy shortage area as one where the distance to a pharmacy is greater than 10 miles in a rural area, 2 miles in a suburban area, 1 mile for urban areas and a half-mile in neighborhoods that are low income and have low vehicle ownership.

Earlier work by Qato found that one-third of neighborhoods in the largest U.S. cities — including Los Angeles — are a pharmacy desert. The most impacted neighborhoods are segregated Black or Hispanic/Latino communities within these cities.

“If you don’t have a car and have problems walking, bus connections are bad, the weather is inclement and you have a child who needed that antibiotic yesterday for a raging infection, a mile can be impossible,” said Qato. “A half-mile can be 30 miles in terms of time and effort.”

Mapping a need for better policy

Qato hopes the mapping tool will inform federal and state policy changes that improve health equity.

For example, Medicare Part D and Medicaid health plans have pharmacy networks that often exclude independent (and some chain) pharmacies that largely serve Black and Hispanic/Latino populations. Qato said such policies are a form of structural racism that forces historically marginalized populations to travel farther to their nearest pharmacy to fill their medications.

Excluding pharmacies from networks also leads to the underutilization — and, often, closure — of pharmacies located in these neighborhoods, Qato said.

“Reimbursement is the main issue in pharmacy closures that contribute to pharmacy deserts,” said Ronna Hauser of the National Community Pharmacists Association and a co-director with Qato on the pharmacy access project. “States are making it more obvious that they want to help pharmacies succeed and continue to stay open in these underserved areas.”

Map helps address inequitable implementation of policies and pharmacy reimbursement

The map not only reveals the pharmacy deserts across the country, but could also provide a framework to promote accountability — including in the regulation of pharmacy benefit managers, who play an important role in low and inequitable pharmacy reimbursement and pharmacy closures.

“In terms of the equitable implementation of federal and state policies, it’s important to ensure that local pharmacies are actually stocking essential medicines and offering essential services they are authorized to provide,” Qato said.

For example, Qato said that pharmacists in California and some other states can prescribe and dispense contraceptives and pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) medications for HIV prevention. Pharmacies in all states are also allowed to dispense buprenorphine for the treatment of opioid use disorder or naloxone, an opioid overdose antidote.

Although pharmacists are authorized for those services, Qato explained access remains a problem for the underserved: “Our research has shown that many pharmacies either do not stock these medicines or do not provide these services — especially in underserved neighborhoods that need them most.”

Mapping the risk of people not taking their medication

Lastly, the mapping tool can also provide important insights about the neighborhoods at risk of becoming pharmacy deserts.

“My work in Chicago and elsewhere, including Los Angeles, has found that predominantly Black and Hispanic neighborhoods have fewer pharmacies, and they are also more likely to experience closures. Closures impact medication adherence,” Qato said. “We found that people who have filled a prescription at a pharmacy that subsequently closed are more likely to discontinue their prescription drugs.”

Vos notes that the mapping tool was developed with user-friendly Web GIS software design. The tool will be rolled out via training webinars for stakeholders in the coming months.