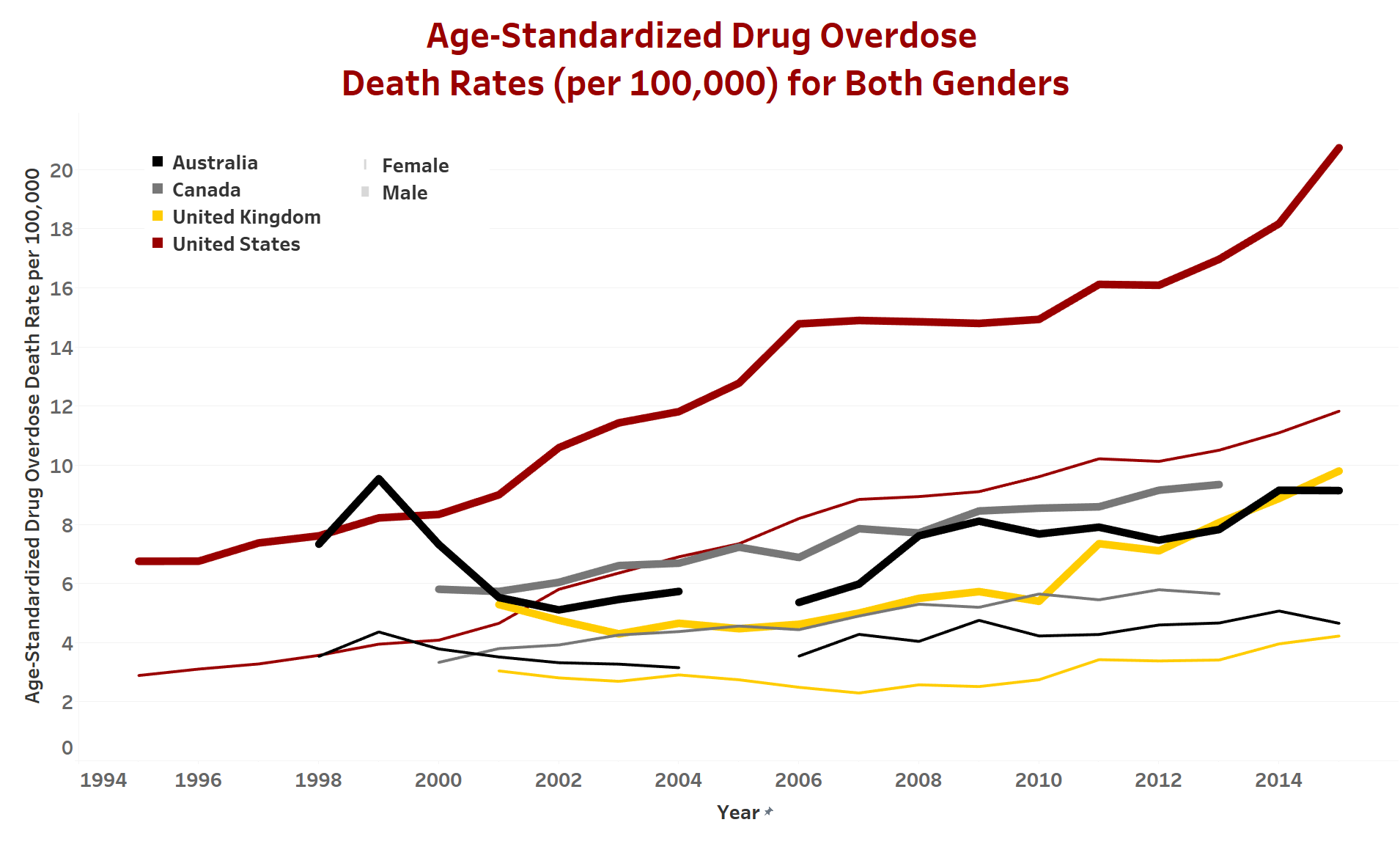

In the most comprehensive international comparison of its kind, a USC study found that the United States has the highest drug overdose death rates among a set of high-income countries.

Drug overdose mortality has reached unprecedented levels in the United States, more than tripling over the past two decades. But is this a uniquely American epidemic, or are other high-income counties facing a similar crisis?

“The United States is experiencing a drug overdose epidemic of unprecedented magnitude, not only judging by its own history but also compared to the experiences of other high-income countries,” said study author Jessica Ho, assistant professor at the USC Leonard Davis School of Gerontology. “For over a decade now, the United States has had the highest drug overdose mortality among its peer countries.” Ho was a 2017-2018 RCMAR fellow in the USC Minority Aging Health Economics Research Center at the USC Schaeffer Center.

The study, published February 21 in Population and Development Review, found that drug overdose death rates in the United States are 3.5 times higher on average when compared to 17 other high-income counties. The study is the first to demonstrate that the drug overdose epidemic is contributing to the widening gap in life expectancy between the United States and other high-income countries.

Drug overdose deaths cut into American life expectancy

The study found that prior to the early 2000s, Finland and Sweden had the highest levels of drug overdose mortality. Drug overdose mortality in the United States is now more than 27 times higher than in Italy and Japan, which have the lowest drug overdose death rates, and double that of Finland and Sweden, the countries with the next highest death rates.

By 2013, drug overdose accounted for 12 percent and 8 percent of the average life expectancy gap for men and women, respectively, between the United States and other high-income countries. Without drug overdose deaths, the increase in this gap between 2003 and 2013 would have been smaller: one-fifth smaller for men and one-third smaller for women.

“The American epidemic has important consequences for international comparisons of life expectancy. While the United States is not alone in experiencing increases in drug overdose mortality, the magnitude of the differences in levels of drug overdose mortality is staggering,” said Ho.

In 2003, life expectancy at birth would have been 0.28 years higher for American men and 0.17 years higher for American women in the absence of drug overdose deaths. Ten years later, these figures had increased to 0.45 years for American men and 0.30 years for women. In both 2003 and 2013, the United States lost the most years of life from drug overdose among high-income countries, with the difference increasing dramatically over that time period.

“On average, Americans are living 2.6 fewer years than people in other high-income countries. This puts the United States more than a decade behind the life expectancy levels achieved by other high-income countries. American drug overdose deaths are widening this already significant gap and causing us to fall even further behind our peer countries,” Ho said.

A uniquely American phenomena – but will it stay that way?

Over 70,000 people died from drug overdoses in the United States in 2017, and the National Safety Council announced in January that Americans are now more likely to die of an accidental opioid overdose than in a car crash.

Potential drivers of the country’s strikingly elevated drug overdose mortality levels include health care provision, financing and institutional structures, such as fee-for-service reimbursement systems and tying physician reimbursement to patient satisfaction. Additional factors include a well-documented marketing blitz by the manufacturers of Oxycontin, American cultural attitudes towards pain and the medical establishment, and the scarcity of substance abuse treatment in the United States, where only an estimated 10 percent of those with a substance abuse disorder receive treatment.

Despite its rapid ascent to the top of this tragic list, the United States may soon have competition for its dubious distinction. Ho points to the potential for drug overdose mortality to increase in other countries in the near future, noting similar and troubling patterns in Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom.

While opioids became a cornerstone of pain treatment in the late 1990s and early 2000s in the United States, other countries either didn’t use strong opioids for pain relief or placed greater restrictions on their use. Exceptions include Australia, which experienced a switch from weak to strong opioids that is reflected in its 14-fold increase in oxycodone consumption between 1997 and 2008, and Ontario, Canada, which saw an 850 percent increase in oxycodone prescriptions between 1991 and 2007. Both countries also experienced large increases in drug overdose mortality.

Although the current American epidemic started with prescription opioids, it is now rapidly transitioning to heroin and fentanyl. European countries may be on the opposite trajectory, which could nonetheless result in more drug overdose deaths over time. “The use of prescription opioids and synthetic drugs like fentanyl are becoming increasingly common in many high-income countries and constitute a common challenge to be confronted by these countries,” Ho said.

The USC study utilized data on cause of death from the Human Mortality Database and the World Health Organization Mortality Database for the set of 18 countries, along with additional data from vital statistics agencies in Canada and the United States to produce country-, year-, sex-, and age-specific drug overdose death rates between 1994 and 2015. Deaths from both legal and illegal drugs (not limited to opioids) and deaths of all intents were included.

This work was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development at the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R00 HD083519, by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health under Award Numbers P30 AG043073 and R01 AG060115, and by a grant from the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (#74439).

You must be logged in to post a comment.