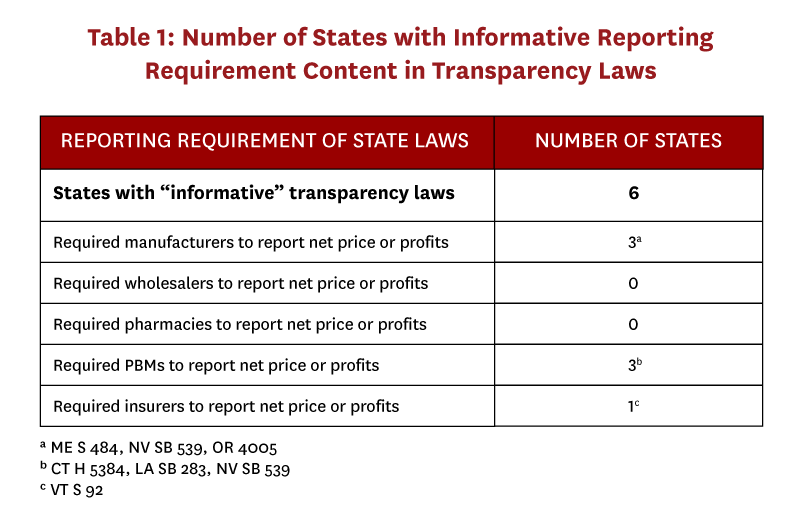

We analyzed 166 recently enacted prescription drug pricing laws to identify those that contained price transparency measures that could improve understanding of the economic forces driving drug price increases. We find that six states (CT, ME, NV, OR, VT, LA) enacted effective transparency laws, but no state legislation required release of real transaction prices at each stage of the pharmaceutical distribution process. Knowing real transaction prices at each stage is a necessary prerequisite for policymakers seeking effective solutions that reduce drug prices through eliminating excess drug distribution system profits. A new approach to price transparency legislation that requires each drug distribution entity (pharmacies, pharmacy benefit managers, wholesalers, manufacturers, and insurers) to disclose transaction prices would be more effective.

Editor’s note: An interactive map and table of the transparency laws identified and analyzed by the authors is available here.

Introduction

Prescription drugs accounted for 19 percent of all Medicare spending in 2016,[1] and steeply increasing drug prices have provoked public outcry for government intervention. According to a recent poll of American patients, 24 percent have difficulty affording their prescriptions,[2] and voters have ranked healthcare as their number one priority for the 2020 presidential election.[3] However, because few people outside the pharmaceutical distribution system know which entities in the system are making excess profits, policymakers struggle to draft effective legislation to lower drug costs for consumers and public payers.[4,5]

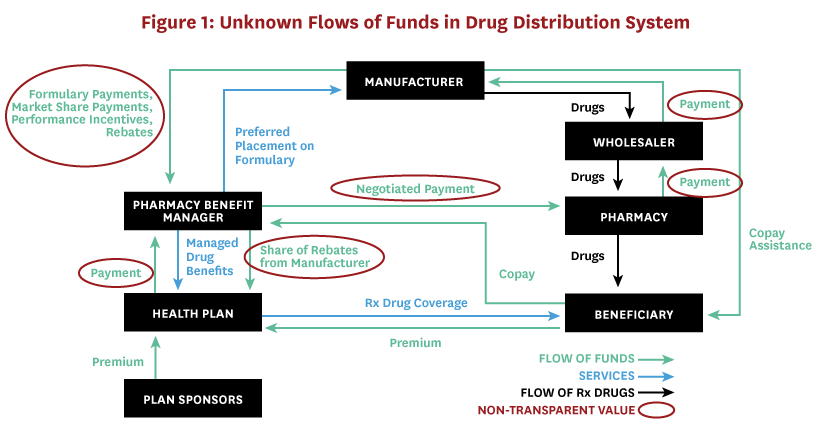

Public attention tends to focus on drugs’ list prices (or wholesale acquisition cost [WAC]), likely because these data are the most widely available to those outside the industry.[6,7] WAC is a list price upon which manufacturers base the price they charge to wholesalers, but due to rebates and other concessions, it does not represent the amount that manufacturers ultimately receive for drugs. The complexity of the drug distribution system, involving numerous middlemen and confidential negotiations for myriad rebates, fees and discounts, ensures that list prices have little to do with the prices eventually paid by consumers and payers (Figure 1).

The drug’s manufacturer net price is a more useful indicator of the total price paid after all discounts and rebates, and represents the amount the manufacturer ultimately receives. Transaction prices, i.e. those that distribution system entities negotiate with one another, are also useful and important for calculating excess profits – the returns earned above and beyond the risk-adjusted rewards that would be earned in a competitive market. Estimates of manufacturer net price per unit for 49 top-selling (those exceeding $500 million in domestic sales and 100,000 pharmacy claims) brand-name prescription drugs in the US increased an average of 9 percent from the three to five years preceding 2017.[8] But the difference between what manufacturers receive for each drug and the profits distributed among parties that make up the pharmaceutical distribution system, including wholesalers, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), insurers, and pharmacies, is shrouded in mystery. As a result, some legislatures are proposing policies designed to increase transparency in the drug distribution system.

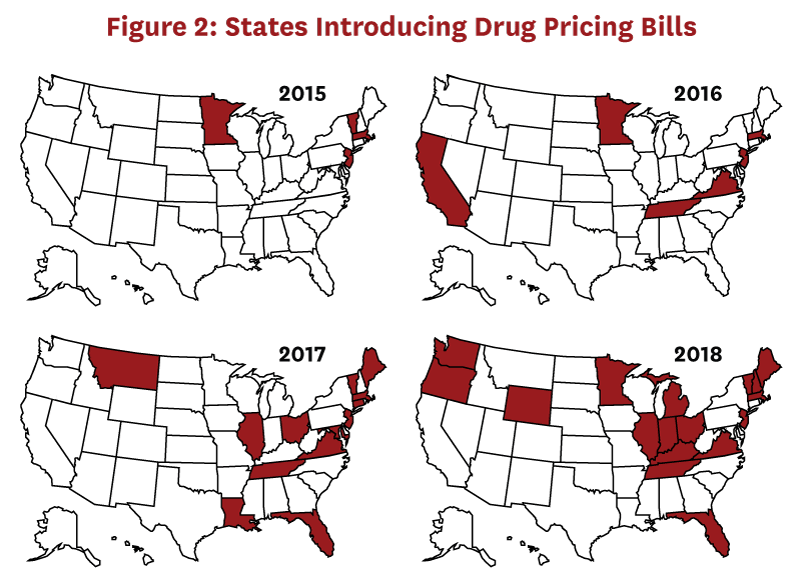

Although federal agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration and the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services regulate important aspects of the pharmaceutical industry, individual state laws control many aspects of the pharmaceutical distribution system. The process of legislation (enacting new laws) differs from that of regulation (the implementation of enacted laws). States are increasingly introducing drug pricing bills (Figure 2), many of which are focused on price transparency. These are designed with the intent to provide regulators or the public with more information about how entities in the drug distribution system set prices, particularly when prices increase suddenly or steeply.[9] Presumably, having such information will help regulators determine when and how to intervene when distribution system entities make price increases that result in excess profits.[10] Transparency laws may also preempt some unwarranted price increases as distribution system entities realize they will have to report prices and thereby invite scrutiny.[11]

To understand whether this legislative activity is likely to provide the information needed to understand whether drug distribution players are making excess profits, we reviewed recent state drug price transparency laws. This analysis was published in a peer-reviewed journal: JAMA Network Open.[12] Below, we describe the methods, key results, and implications of this analysis.

Methods

To identify transparency bills, we searched the National Conference of State Legislatures (NCSL) prescription drug database, which tracks state drug laws from 2015 onward.[13] We initially captured all enacted laws related to drug pricing, and later restricted the sample to only those that included a component of information transparency in the legislation summary. We also used the National Academy for State Health Policy[14] and the American Health Lawyers Association[15] state legislative surveys to identify legislation not included in the NCSL database. These surveys accounted for about 35 percent of our sample.

We first categorized laws according to the entity from which the law required information (manufacturers, wholesalers, PBMs, pharmacies, insurers, or a combination). We then analyzed each law’s potential to reveal information about distribution system participants’ rebates, concessions, manufacturer net prices, or profits. We chose these criteria because knowing real transaction prices is a vital prerequisite to understanding where and how to focus policy solutions. Accordingly, we coded laws as “informative” if they would result in new disclosure of this information. Laws requiring reporting of information that was already publicly available (such as wholesale acquisition costs), or that did not help reveal the drug’s multiple transaction prices (such as justifications for a price increase) were labeled “uninformative,” because they would not reveal true transaction prices that were not previously available elsewhere.[5,12]

Results

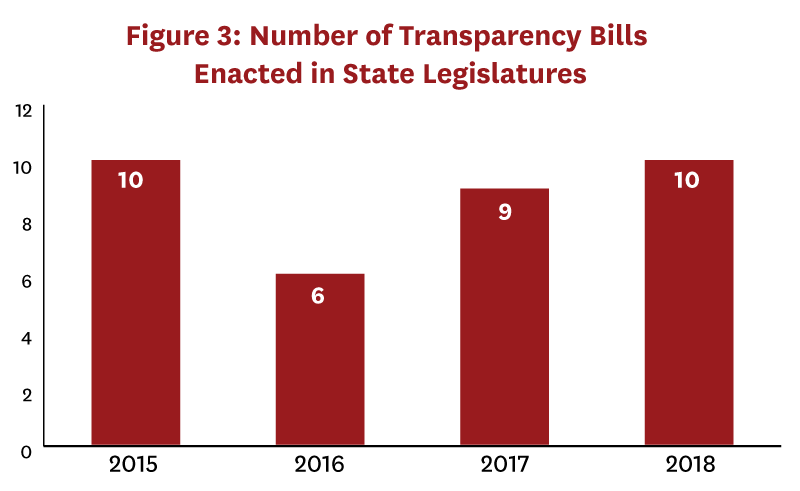

We identified 166 drug pricing bills enacted during 2015-18, of which 35 bills in 22 states included a transparency component (Figure 3). Only seven of these bills, passed in six states, were determined to be “informative.” (Table 1). Two states required that transaction prices be reported—in Vermont insurers were required to report specific drug costs net of rebates, and in Maine manufacturers were required to report “true net typical prices charged to the PBM.”[16] Only Oregon and Nevada required that profits be reported—in both states by manufacturers. Laws in Connecticut, Louisiana, and Nevada required PBMs to report aggregate rebates, but no state required reporting rebates at the drug level. “Uninformative” transparency laws commonly required distribution system participants to disclose their methodology for setting prices or formulary design, provide advance notice of list price increases, or register with a government regulatory body.

Laws vary on several dimensions, including the timing of the disclosure (before or after a price increase), the type of information (e.g. price amounts, justification for price increase, pricing methodology, etc.), and what thresholds trigger disclosure. In many cases, information submitted to the state is kept confidential, and in some states the receiving agency must generate a public report summarizing the information submitted by manufacturers. In other cases, the legislation contains no apparatus for further state action or enforcement. These details will influence whether the public will have access to data or not, and the extent to which regulations have teeth. The number of drugs required to be reported, and from which entities the transparency is required are the most important factors because they determine the amount of information released.

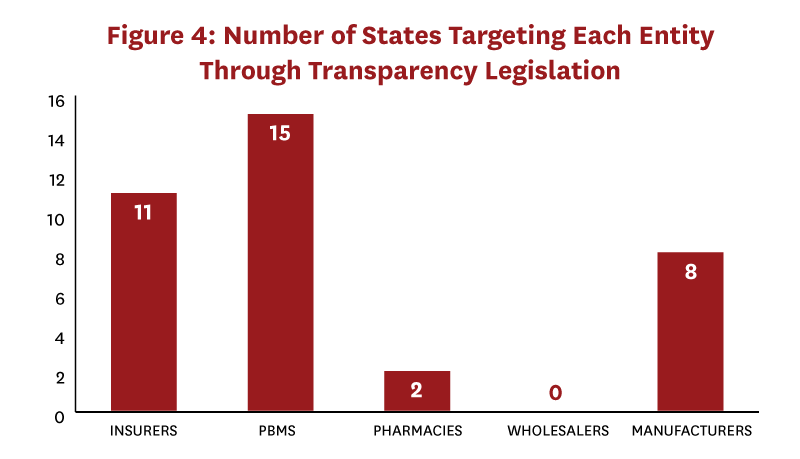

Most states with transparency laws (whether informative or uninformative) targeted PBMs or insurers; very few laws targeted pharmacies or wholesalers (Figure 4).[12] While three states passed laws that targeted two distribution system segments (CA, OR, and VT), only Nevada and Vermont passed laws targeting three distinct distribution system segments (manufacturer, insurer, PBM). No state targeted more than three of the five possible segments. Importantly, no state passed laws that together revealed true transaction prices or profits across all distribution system segments.

Discussion

Clarifying who along the distribution system is responsible for and benefiting from increased prices can inform efforts to address drug pricing.[17] Excess profits in the distribution system harm patients with and without insurance. Those without insurance or who are insured but in the deductible portion of the benefit have been shown to reduce utilization of medications in response to higher out-of-pocket costs,[18,19] resulting in worse outcomes.[20] Even if insured patients pay low out-of-pocket costs for their medications, rising drug costs might result in higher premiums over time. Based on our review, the state legislation currently in place to provide greater transparency is insufficient to properly guide any targeted policy action necessary to identify and eliminate excess profits in the distribution system.

The conclusion that states are passing mostly uninformative transparency laws raises the question of why they engage in such efforts in the first place. One explanation is that although appealing in principle, implementing transparency meaningfully is much harder in practice. Legislators may win voter support if they demonstrate their commitment to the cause of lower drug prices by sponsoring transparency legislation, even if that legislation won’t help lower drug prices. But state legislators also face significant challenges in designing and implementing effective laws, among them ensuring consistency with existing federal law: Nevada’s SB 539 faced a lawsuit (eventually dropped once the state allowed companies to protect specific information from public disclosure[21]) led by the pharmaceutical industry on the grounds that the law violates the dormant commerce clause.[22] Court challenges led by distribution system entity interest groups pose an important hurdle that state legislation must overcome.

Even effective transparency laws on their own do little to affect drug prices without supplementary strategies to act on information resulting from transparency disclosures. Transparency is not the same thing as action. Additional strategies, like consumer incentives and third-party auditing,[23] are necessary for transparency reporting to result in lower drug prices.[10] For example, Vermont’s price transparency reports resulting from Act 165 have identified thousands of drugs that exceed the thresholds provided in its price transparency bill.[24] Yet only ten were selected by a state board for investigation of excessive price increases. If the state lacks the capacity to act upon the information provided through these measures, they will have limited impact on drug prices.

Conclusion

The process of manufacturing, distributing, and paying for pharmaceuticals involves numerous commercial entities.[12,17] Price transparency for just one of these sectors is of limited use for understanding whether and where excess profits are being made in the distribution system. Instead, transparency is required across all actors in the distribution system to understand the end-to-end economics of that system. We find that most bills in the recent flurry of state price transparency activity are of limited impact and none provide complete transparency throughout the distribution system, despite the enormous legislative resources spent to enact them. These significant resources, and the regulatory burden that even ineffective laws impose on drug distribution system entities, should be considered in any accounting of their overall benefit to society.

The most important information for policymakers to include in useful drug price legislation is reporting all transaction price information, including the discounts and rebates received, from each distribution system chain participant.[12] This information is necessary to guide policy solutions targeted at those in the distribution system making excess profits. Policymakers should start by prioritizing this information for drugs with the largest budget impact or price increases. Ideally, state laws should require drug-level disclosures.

To view an interactive map and table of the 35 bills analyzed, click here.

References

- Kaiser Family Foundation. 10 Essential Facts About Medicare and Prescription Drug Spending. 2019; https://www.kff.org/infographic/10-essential-facts-about-medicare-and-prescription-drug-spending/.

- Kaiser Family Foundation. Poll: Nearly 1 in 4 Americans Taking Prescription Drugs Say It’s Difficult to Afford Their Medicines, including Larger Shares Among Those with Health Issues, with Low Incomes and Nearing Medicare Age. 2019; https://www.kff.org/health-costs/press-release/poll-nearly-1-in-4-americans-taking-prescription-drugs-say-its-difficult-to-afford-medicines-including-larger-shares-with-low-incomes/.

- The Hill. Health care tops Americans’ list of issue priorities in new poll. 2019; https://thehill.com/hilltv/what-americas-thinking/444045-health-care-tops-americans-list-of-issue-priorities-in-new-poll.

- Cefalu WT, Dawes DE, Gavlak G, et al. Insulin Access and Affordability Working Group: Conclusions and Recommendations. Diabetes Care. 2018;41(6):1299-1311.

- Council of Economic Advisers. Reforming Biopharmaceutical Pricing at Home and Abroad. 2018; https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/CEA-Rx-White-Paper-Final2.pdf.

- First Databank. FDB MedKnowledge Drug Pricing. https://www.fdbhealth.com/.

- HHS Finalizes Rule Requiring Manufacturers Disclose Drug Prices in TV Ads to Increase Drug Pricing Transparency [press release]. 2019. https://www.hhs.gov/about/news/2019/05/08/hhs-finalizes-rule-requiring-manufacturers-disclose-drug-prices-in-tv-ads.html.

- Wineinger NE, Zhang Y, Topol EJ. Trends in Prices of Popular Brand-Name Prescription Drugs in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(5):e194791-e194791.

- Findlay S. States Pass Record Number Of Laws To Reel In Drug Prices. Kaiser Health News 2019; https://khn.org/news/states-pass-record-number-of-laws-to-reel-in-drug-prices/.

- Sarpatwari A, Avorn J, Kesselheim AS. State Initiatives to Control Medication Costs — Can Transparency Legislation Help? New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;374(24):2301-2304.

- Elgin B, Koons C, Langreth R. Drugmakers Cancel Price Hikes After California Law Takes Effect. Bloomberg 2018; https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2018-07-10/drugmakers-cancel-price-hikes-as-california-law-takes-effect.

- Ryan MS, Sood N. Analysis of State-Level Drug Pricing Transparency Laws in the United States. JAMA Network Open. 2019;2(9):e1912104.

- National Conference of State Legislatures. Statewide Prescription Drug Database: 2015-Present. 2019; http://www.ncsl.org/research/health/prescription-drug-statenet-database.aspx.

- National Academy for State Health Policy. State Legislative Action to Lower Pharmaceutical Costs. 2019; https://nashp.org/rx-legislative-tracker-2019/.

- Chapman EJ. Pharmacy Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) Laws: A 50 State Survey. American Health Lawyers Association;2017.

- 128th Maine Legislature. An Act To Promote Prescription Drug Price Transparency. In. Sec. 1. 22 MRSA §26982017.

- Sood N, Shih T, Van Nuys K, Goldman DP. Follow The Money: The Flow Of Funds In The Pharmaceutical Distribution System. Health Affairs Blog 2017; https://www.healthaffairs.org/do/10.1377/hblog20170613.060557/full/. Accessed June 13, 2017.

- Piette JD, Heisler M, Wagner TH. Cost-related medication underuse among chronically ill adults: the treatments people forgo, how often, and who is at risk. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(10):1782-1787.

- Goldman DP, Joyce GF, Zheng Y. Prescription drug cost sharing: associations with medication and medical utilization and spending and health. JAMA. 2007;298(1):61-69.

- Sable-Smith B. Insulin’s High Cost Leads To Lethal Rationing. NPR 2018; https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2018/09/01/641615877/insulins-high-cost-leads-to-lethal-rationing.

- Messerly M. Big Pharma abandons lawsuit over Nevada’s insulin pricing transparency law after state approves trade secret protection regulations. The Nevada Independent 2018; https://thenevadaindependent.com/article/big-pharma-abandons-lawsuit-over-nevadas-insulin-pricing-transparency-law-after-state-approves-trade-secret-protection-regulations.

- Lee TT, Kesselheim AS, Kapczynski A. Legal challenges to state drug pricing laws. JAMA. 2018;319(9):865-866.

- Gudiksen KL, Brown TT, Whaley CM, King JS. California’s Drug Transparency Law: Navigating The Boundaries Of State Authority On Drug Pricing. Health Affairs. 2018;37(9):1503-1508.

- Vermont General Assembly. An act relating to prescription drugs. In. Sec. 2. 18 V.S.A. § 46352016.

Eye on PBMs

Following the Money

Schaeffer research reveals how inefficiencies in the drug supply chain increase costs and limit access

Our Research on PBMs