Editor’s note: This story was first published by The Orange County Register on December 30, 2021 and written by Claudia Boyd-Barrett.

Amparo Miramontes and her husband thought they’d found the perfect place to raise a family when they moved with their baby daughter from Burbank to Fontana in 2010.

They bought a spacious, five-bedroom home for a fraction of the cost of anything equivalent in Los Angeles. The neighborhood was safe, rural and friendly. They barely noticed the nearby landfill and the small but growing collection of online shopping warehouses.

Then they started getting sick.

Miramontes was constantly wiping mucus from her daughter’s nose, and taking her to the pediatrician’s office to be treated for respiratory infections. Allergies, the doctor said.

Within a couple of years, Miramontes herself was struggling to breathe. At 34, she was diagnosed with asthma, even though she had no history of the condition. When she became pregnant with her second child, in 2013, the doctors induced the baby four weeks early because Miramontes’ oxygen levels were dangerously low. Her newborn son also had breathing difficulties.

“Finally I started asking the question: What could cause this?” Miramontes said. “I talked to the doctor about it and he told me there was something called PM 2.5 (referencing fine particulates in smoggy air), and that it was linked to a lot of symptoms they were seeing all over the world for kids exposed to high pollution levels.”

Researchers have known for decades that air pollution is bad for people’s health, but only recently have they begun to understand the full extent of the danger. Babies and young children are especially at risk from toxins in the air because their bodies are still developing, and they breathe in proportionally more air than adults. And new research suggests that growing into adulthood in smoggy communities can result in permanent, life-altering damage.

An ongoing study of more than 12,000 school children by the University of Southern California found that those exposed to high levels of air pollution had smaller and more unhealthy lungs by the time they reached adulthood than did those who breathed cleaner air. Now, researchers are looking into the possibility that early exposure to smog might even alter DNA, possibly harming subsequent generations.

Stanford University researchers recently discovered that breathing dirty air alters gene expression in young children in a way that could predispose them to heart disease as adults. And a growing number of studies have linked early exposure to air pollution to other, potentially life-long ills including obesity, developmental delays, ADHD, autism, preterm birth and birth defects.

“There’s just an enormous body of evidence that suggests these early windows of exposure” affect children’s health, said Tracy Bastain, an associate professor in the Department of Population and Public Health Sciences at USC’s Keck School of Medicine.

“Air pollution impacts can be (felt) across the lifespan, and these early periods, especially prenatal periods when the fetus is developing, and during the early childhood periods…are particularly sensitive.”

Children in the Inland Empire are among those at highest risk.

The region is the smoggiest in the nation, according to the American Lung Association. Specifically, San Bernardino and Riverside counties rank among the top 10 counties in the United States for year-round particle pollution, a precursor to smog that includes PM 2.5, or particulate matter 2.5 – tiny, airborne droplets that penetrate deep into the lungs and are linked to increased rates of respiratory illness, heart disease and premature death.

The problem has worsened in San Bernardino County since around 2015, when air pollution levels started ticking up after years of decline. Riverside County has fared better, but the number of high ozone days has also been trending upwards. Both counties received a “Fail” grade for air quality in the American Lung Association’s most recent State of the Air report.

Now, some parents in the Inland Empire are sounding the alarm. They say their kids are battling asthma, persistent nosebleeds and other ailments that studies show can be linked to air pollution.

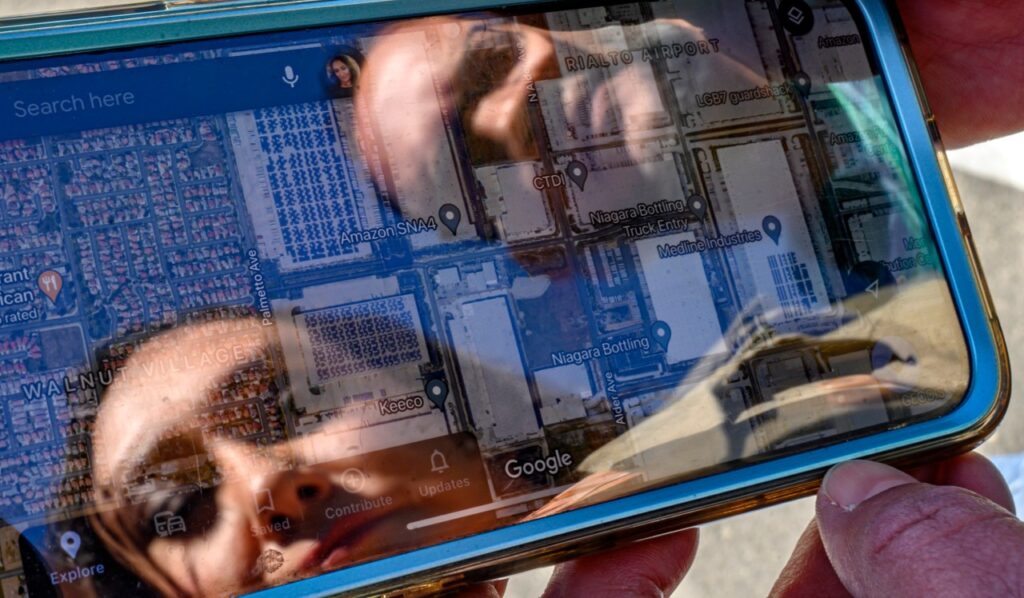

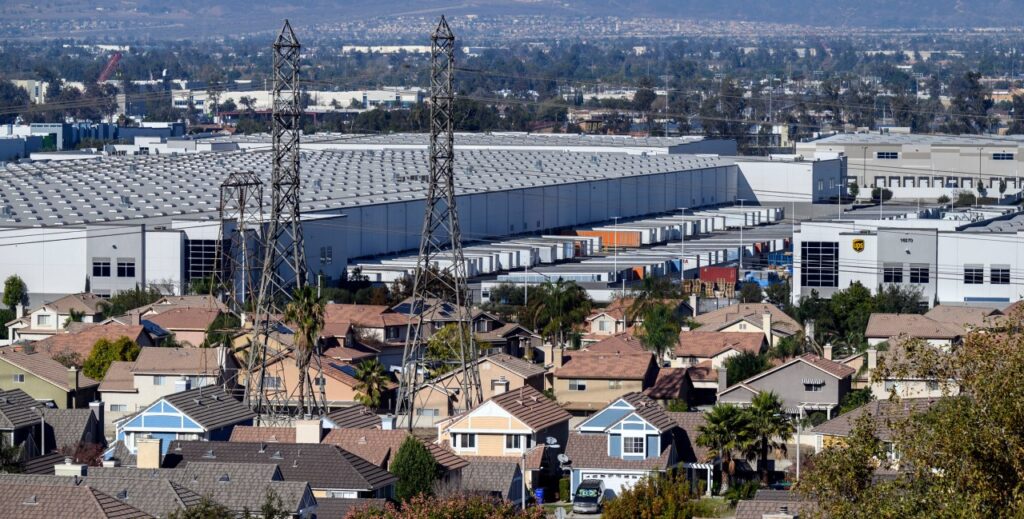

Many believe the recent drop in air quality is the result of an explosion in online shopping warehouses and logistics led by retail giant Amazon, a trend that is driven by soaring consumer demand for home-delivered goods. The new industry has brought heavy truck and freight traffic off the freeways and into communities such as Fontana and San Bernardino. That’s on top of the region’s existing geographic and topographic challenges, particularly its location beside several mountain ranges, which results in the accumulation of pollution that originates in coastal areas such as Los Angeles and Orange counties.

And many researchers say climate change is almost certainly playing a role in the new wave of pollution. Hotter temperatures combined with traffic exhaust creates ideal conditions for the formation of smog. Climate change also is making wildfires more common and bigger, creating longer periods of elevated smoke in the region’s air — another reason behind the downturn in local air quality.

Dr. Afif El-Hasan, an Orange County pediatrician in San Juan Capistrano and a spokesperson for the American Lung Association, said people should be “extremely concerned” about pollution levels in the Inland Empire and the risks to children living there. In the short-term, air pollution inflames children’s airways and affects their ability to fight off infection, leading to more frequent asthma attacks and respiratory illnesses. In the long-term, he said, those children are more likely to develop heart disease, cancer, emphysema and other health problems as adults.

“If you’re basically condemning these children to reduced lung capacity for their lives, and not giving them healthy air to breath, they’re going to have problems later on, whether it’s going to be directly in the lungs or in another part of their bodies.”

Unless action is taken to clean the region’s air, he added, “it is going to affect the allocation of resources later on, when all of these kids who were exposed to all this air pollution become very sick and require expensive treatment.”

Dr. Brett Cherry, an allergist and immunologist at Riverside Medical Clinic, often sees patients, including children, with allergy symptoms such as itchy eyes or a constantly runny nose, who test negative for typical allergens such as pollen and pet dander. What they’re actually reacting to, Cherry said, is polluted air.

“Sometimes they joke that my prescription should be, ‘move to the beach’.”

Instead, Cherry advises them to stay indoors when the air is particularly bad, run air conditioning to filter the air whenever possible, and be aware of anything that triggers their symptoms. In some cases where this doesn’t help, he prescribes medications.

Among Cherry’s older patients are people who grew up in the region during the 1960s and ‘70s, when air pollution in the Inland Empire was far worse, and smoking was more prevalent. Many of those patients have dealt with allergies and asthma since they were children; some now battle chronic lung disease. To them, the air quality these days – even with the recent retrenchment – isn’t, by comparison, bad, Cherry said. But to him, he added, the region’s air is concerning, particularly with the recent increase in wildfires and smoke.

Indoor summer

Leonardo Barrera can’t write his name or tie his shoes but, at age 3, he’s a pro at using his inhaler.

His mother, Roxana Barrera, said he’s suffered breathing difficulties most of his short life and that she and her husband keep him inside when outdoor air poses a risk. But last summer, she added, there were so many smoggy days in their San Bernardino community that Leonardo was kept indoors pretty much all the time.

“It’s hard to tell a kid not to run. He just wants to run everywhere. He wants to be wild and free,” she said. “I worry that when he’s older he’s still going to have these issues. He’s still going to have to use an inhaler.”

The Barrera family live close to dozens of logistic center warehouses and the San Bernardino BNSF Railyard, one of the biggest and busiest logistics hubs in California. Trucks constantly rumble up and down the nearby roads; Barrera recently counted 30 semi-trailers at the intersection nearest her home in the time it took the light to turn green.

Young Leonardo isn’t alone in his battle to breathe. Many other kids in the neighborhood, Barrera noted, seem to have asthma and respiratory problems.

A 2015 study of elementary school children in Barrera’s community confirms what she’s noticed anecdotally.

Lead researcher Rhonda K. Spencer-Hwang at the Loma Linda University School of Public Health said she was surprised and angered to discover that children living in Barrera’s neighborhood were much sicker than kids who went to school just seven miles away. The problem has likely worsened since the study was conducted, given the increase in air pollution, she added. And while children across the Inland Empire are exposed to bad air quality, Spencer-Hwang said those living closest to key sources of pollution, such as the railyard, are hurt the most.

Referencing children in the study, she said breathing the polluted air “impacted their ability to blow out.”

In surveys, the parents reported significantly more asthma among their kids and that they thought “a chronic cough was normal, like a smoker’s cough, because they all had it.”

Dr. Barbara Ariue, a pediatric allergist with Loma Linda University Children’s Hospital, said this trend plays out among the young patients she sees.

Babies and children from low-income neighborhoods like Barrera’s are more likely to live near transportation hubs and busy roads, and endure respiratory problems as a result. Those families often don’t have air conditioning, or can’t afford to run it, so they open windows when it gets hot, inviting dirty air into their homes and, inadvertently, their children’s lungs.

Parents take action

Liz Sena, a nurse’s assistant and mother of two young children, had long been bothered by two related issues – South Fontana’s bad air quality, and the number of warehouses popping up in the community.

Isolated at home during the pandemic, Sena began chatting with other residents on Facebook and realized she wasn’t alone with her concerns. Many residents complained about the local haze, a condition in which the air is so thick they couldn’t see the nearby San Bernardino Mountains. They shared posts about frequent headaches and shortness of breath, and about how their kids repeatedly suffered nosebleeds or seemed to need more and more asthma medication.

“I realized that this is real. If so many of us are sharing the same stories… this isn’t just happening to one or two people,” Sena said.

“We started to say, ‘How do we do something about this?’”

So Sena and like-minded residents formed the South Fontana Concerned Citizens Coalition. The group attends city council and planning commission meetings, seeking stricter regulation of warehouse development and air quality, and calling for a reduction in truck traffic and more investment in parks and green spaces. They’ve protested against warehouse projects near homes and schools.

Their actions and those of other environmental and community activists in the region have garnered some results.

In July, State Attorney General Rob Bonta filed a lawsuit against the City of Fontana following the city’s approval of a nearly 206,000-square-foot warehouse project by Duke Realty Corp., arguing that the city failed to properly review and mitigate environmental concerns. Earlier this year, the South Coast Air Quality Management District board, which regulates air quality in the region, approved a landmark rule that will require large warehouse operations – those 100,000 square feet or more – to reduce their impact on air quality by transitioning to electric trucks or installing solar panels, among other measures.

Dr. Sarah Rees, Deputy Executive Officer for Planning and Rule Development at South Coast Air Quality Management District, said the rule – which takes effect in 2022 — is expected to reduce air pollution in communities near warehouses and transportation corridors. The California Air Resources Board also recently took unprecedented action to reduce emissions from trucks.

But Rees said more change will be required from the federal government to bring down emissions enough to improve air quality and community health. Over 80 percent of the emissions that form smog come from mobile sources, and most of those are from heavy-duty trucks, as well as ships and locomotives, Rees added.

“We’re working hard to partner with (the Environmental Protection Agency) and other entities in the federal government to make them understand the urgency… so that they can help us work together to clean up the air.”

Still, some parents worry change won’t be big enough, or happen fast enough, to protect their kids and undo damage that’s already happened.

Ana Gonzalez, a Rialto resident and executive director of the Inland Empire-based Center for Community Action and Environmental Justice, said parents fear their kids won’t live as long because of the poor air quality. She added that her own son was recently diagnosed with asthma at age 15, three years after developing severe bronchitis and pneumonia.

“You almost feel guilty for living in an area where you’re putting your own kids, you’re exposing them to this danger,” she said. “But when you’re a single parent that’s all you can afford.”

Meanwhile, Amparo Miramontes said she and her husband have done what they can to counter the air pollution around them. They’ve installed air filters throughout their home, bought new windows to keep the dust out, added purifying plants. They send their kids to school in Upland, where the air is cleaner, and take them to swimming lessons at an indoor pool. It’s helped, she said. But her son, who is now 8, still gets nosebleeds two to three times a week and has asthma. He also recently was diagnosed with autism.

Many others, particularly in low-income neighborhoods like Barrera’s, can’t afford to take the same measures as Miramontes and her family. Around 15 percent of Inland Empire residents lived in poverty as of 2019, according to the Public Policy Institute of California, and more than 40 percent struggle to make ends meet.

Miramontes said she wants health officials to test children in the area for air pollution exposure. She wants warehouse operators to fund indoor recreation centers for kids so they can play in clean air. And she’d like to see commercials on TV explaining what PM 2.5 is and why it’s dangerous.

“I can’t stay silent. I feel like we all have a responsibility to take care of each other,” she said. The warehouses and pollution are “costing us our health. And the very people that are going to have to pay are the kids.”

Claudia Boyd-Barrett reports for The Center for Health Reporting at USC’s Schaeffer Center for Health Policy and Economics. This story was supported by a grant from First 5 LA.

You must be logged in to post a comment.