Editor’s Note: This analysis is part of USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative on Health Policy, which is a partnership between Economic Studies at Brookings and the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics. The Initiative aims to inform the national health care debate with rigorous, evidence-based analysis leading to practical recommendations using the collaborative strengths of USC and Brookings.

Although news stories have focused on the rise in health care premium costs since the Affordable Care Act (ACA) first took effect two years ago, individual market premiums actually dropped significantly, on average, upon the law’s implementation even as consumers got better coverage, according to a new analysis from the Schaeffer Initiative for Innovation in Health Policy published July 22nd in Health Affairs. This trend will hold in 2017, too, even if premiums increase by the 10 or 15 percent rate that some are predicting.

In “Affordable Care Act Premiums are Lower Than You Think,” USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy Associate Director Loren Adler and Initiative Director and Leonard D. Schaeffer Chair in Health Policy Studies Paul Ginsburg find that while parts of the law did increase premiums (guaranteed coverage regardless of health; more uniform premium pricing; requiring “essential” benefits; limits on out-of-pocket costs; and elimination of lifetime coverage limits), other parts lowered premiums by more (market expansion due to the mandate and subsidies; getting more healthy customers; creation of transparent marketplaces and competition), netting an overall savings for consumers.

Ginsburg is also director of public policy at the USC Schaeffer Center for Health Policy & Economics.

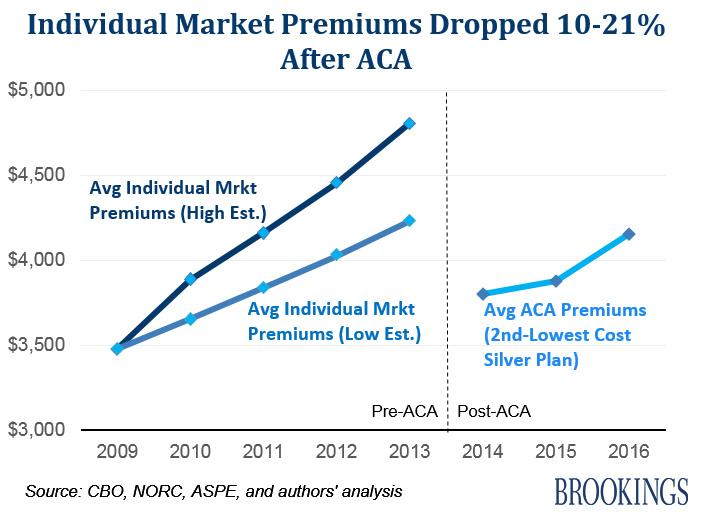

Utilizing Congressional Budget Office (CBO) data, Adler and Ginsburg find that the average annual premium in the individual market in 2009 was $3,480 (or $290 per month), and covered roughly 60 percent of an enrollee’s covered health expenses (an actuarial value of 60 percent), whereas the average premium in 2014 for the second-lowest cost silver-level (SLS) marketplace plan was $3,800 according to CBO, only 9 percent higher despite the passage of five years. Adjusting for the difference in actuarial value, this premium was actually lower in nominal dollars than that in 2009.

The analysis further finds that average premiums in 2014 for the SLS marketplace plan were between 10-21 percent lower than average individual market premiums in 2013, before the ACA, even while providing enrollees with significantly richer coverage (17 percent more of an enrollee’s over health expenses) and a broader set of benefits.

Moreover, ACA marketplace SLS plan premiums are still lower in 2016 than individual market premiums were in 2013, on average, and are a full 20 percent below what the Congressional Budget Office originally estimated they would be during Congressional debate around the law in 2009.

“Health insurance was expensive before the ACA and continues to be, but the ACA appears to have had a salutary impact on premiums even while providing more robust coverage,” they write.

The authors note that some of the recent slower growth in premium costs is the result of the recent larger, system-wide health care spending slowdown, due in part to the slower than expected economic recovery (though growing evidence suggests that the ACA has played some role). But, ACA marketplace premiums have beaten projections by significantly more than other areas of health care spending, implying that the marketplaces have been particularly effective in driving down premiums.

Adler and Ginsburg do caution that premiums through 2016 have likely been too low to be sustainable, as evidenced by the financial difficulties many insurers are having, whether from underestimating the cost of serving new populations or from strategies to build a customer base at an initial loss to them.

“However, barring increases much larger than foreseen today, premiums are likely to remain notably below expectations or where they would have been in the absence of the ACA,” they note. Specifically, Adler and Ginsburg find that “even if ACA marketplace premiums increase by 15 percent in 2017, the average cost of purchasing the second-lowest cost sliver plan would still be roughly 25 percent lower than what an equivalent value plan might have cost in the absence of the ACA.”

“Experiences do differ widely across the nation, though, so consumers in some regions have fared more poorly and some markets suffer from minimal competition. The results of this analysis do not mean that no work remains. Health reform is an ongoing challenge, and there is still much room to increase the quality and competitiveness of marketplaces,” they conclude.